R. Gabrielle Swab

Assistant Professor, Towson University, Department of Management

Jan Baum

Director and Professor of Entrepreneurship, Towson University, Department of Management

Lisa V. Byrd

Director of Events and Business Development, Lead Staff, Baltimore Women’s Advisory Board,

Greater Baltimore Committee

Jennifer Stano

Sr. HR Partner, Towson University, Office of Human Resources

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted labor markets

on a global scale, with employers and employees dealing

with the short-term and long-term sudden and often

severe consequences. Many shuffled to adjust to at-home

work environments, while millions of others were less

fortunate, being furloughed or faced with job loss. Subsequent

pandemic-related research and studies focused

on the macro level of national and global economies,

while small business owners, entrepreneurs, and female

entrepreneurs were largely neglected.

While the economic losses from the pandemic were

huge, the pandemic specifically took a toll on the female

workforce, with female job loss totaling 5.4 million

compared to male job loss at 4.4 million (Ewing-Nelson,

2021; Ellingrud & Segel, 2021). While the years of 2020

and 2021 may be over, the pandemic and the significant

financial insecurity many women and their families are

facing are not (Boesch & Phadke, 2021). However, women

and entrepreneurs create an interesting and unique

context of individuals to consider during a time where

both personal and professional changes are happening

rapidly, and without much foresight into the future.

Female small business owner Carla Nelson Chambers,

founder of The Nelson Ideation Group, says, “as women,

we can turn on a dime”, and as “entrepreneurs, we have

to do that anyway.” She further clarified that “Women are

able to make <those> changes very quickly because we

are so used to, as women, figuring out what is the need

for my family, for my friends, for me.” Entrepreneurs

and women alike have a unique mindset in creating

ways to stay viable, whether it be for their business,

or those around them (e.g., Ambepitiya, 2016; Patil &

Deshpande, 2018).

In this regard, a discussion highlighting female entrepreneurs

as a growing and erudite success story deserving

attention in the pandemic conversation. They represent

a group of emerging business leaders that can teach us

as individuals, managers, or leaders survival skills in

these unprecedented times.

To learn the valuable lessons female entrepreneurs have

to offer, our research team partnered with the Greater

Baltimore Committee (GBC) and its Baltimore Women’s

Advisory Board (BWAB). In doing so, we conducted a

survey to investigate the impact of the pandemic on

women in the workplace within the Greater Baltimore

region. We had a final 433 male and female respondents

across a variety of industries and roles that completed a

survey of questions ranging from organizational support,

job satisfaction, stress, to discrimination. If individuals

identified themselves as an entrepreneur, they were

asked additional quantitative questions related to entrepreneurial

identity and persistence, as well as qualitative

questions regarding their business pre, during, and post

pandemic. From the original 433 participants, we had 18

female entrepreneur respondents within the region that

provided our team with both quantitative and qualitative

data. Based on discussions and feedback from our

sample, we have compiled a look into how this group

is pivoting during the pandemic.

The Sample

Within our sample, we found a mix of entrepreneurs who

had been in business over 20 years, down to those who

had started their business within the year prior to the

pandemic. Among the 18 female entrepreneurs, there

was one in the 26-35 age group, four in the 36-45 age

group, five between 46-55, five between 56-65, two 65

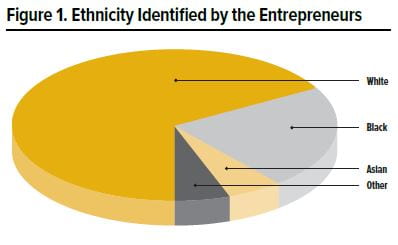

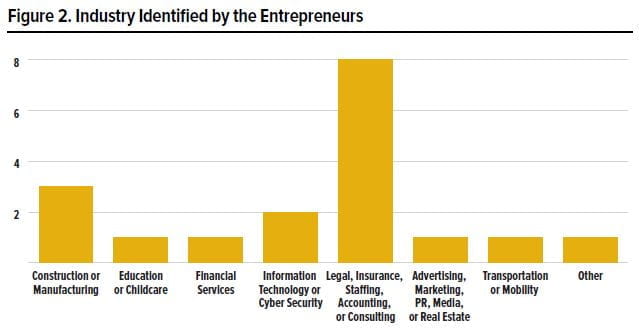

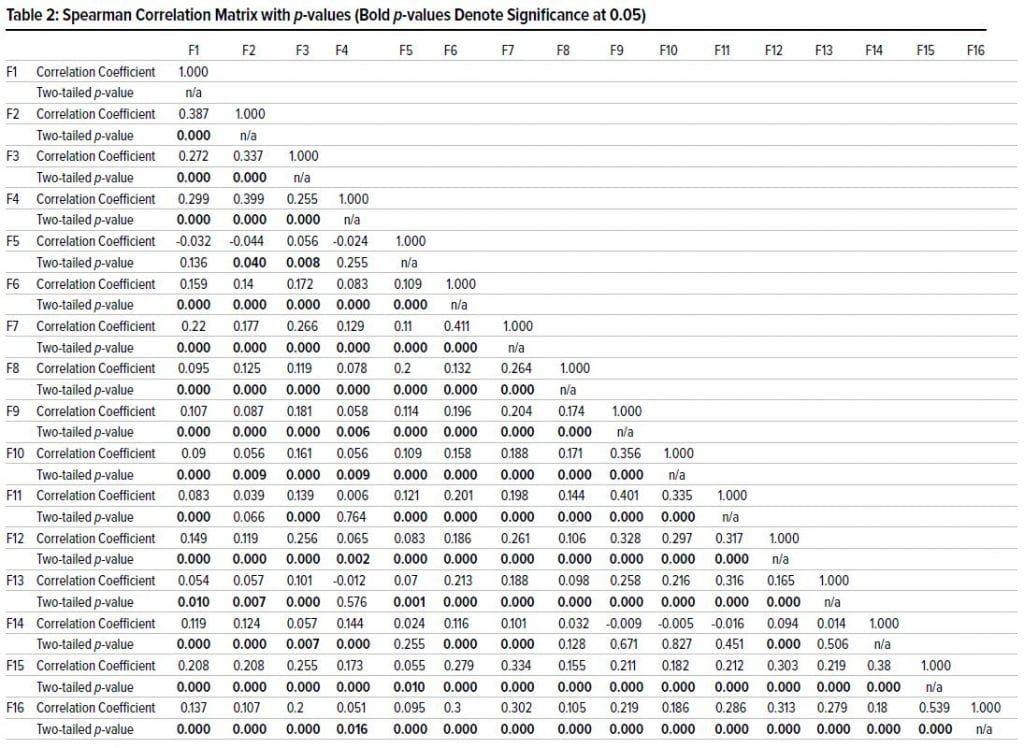

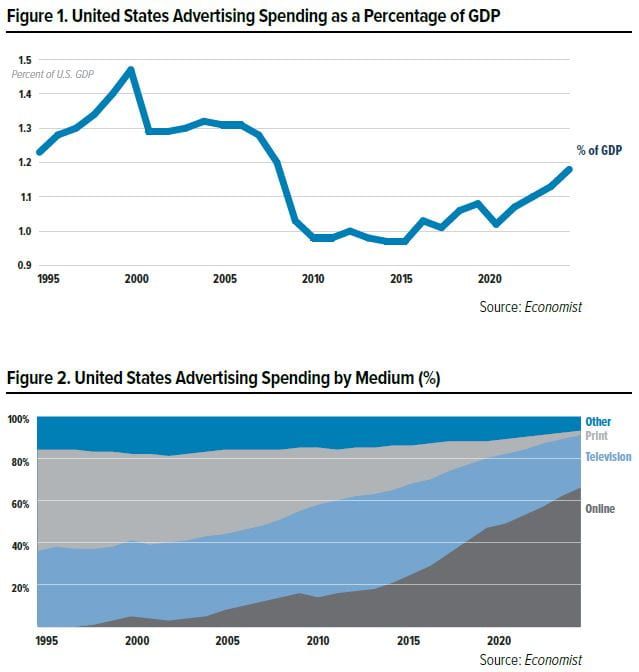

or older, and one did not disclose their age. The ethnic

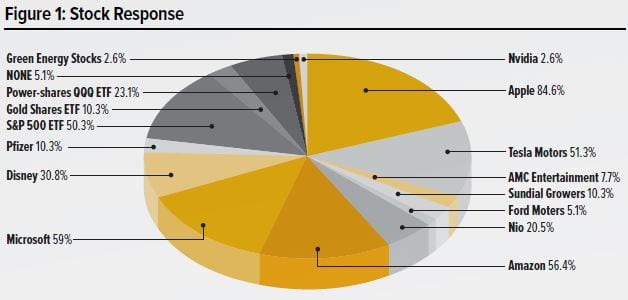

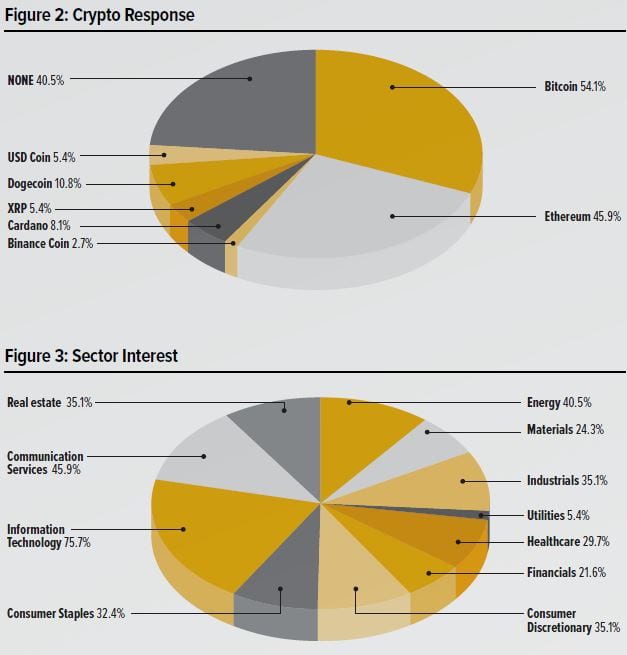

diversity of the entrepreneurs is reported in Figure 1,

while the industry in which the sample identified with

is in Figure 2.

Lessons Learned from an Entrepreneurial Mindset

Entrepreneurs tend to have a more proactive personality,

higher resilience, greater self-efficacy, and a more positive

stress mindset, meaning they respond to challenges with

motivation versus defeat (Li et al., 2020; Neneh, 2019).

However, one does not have to be an entrepreneur, nor

possess all of the aforementioned qualities, to develop

an entrepreneurial mindset. Observations based on

their responses provide insight into the mindset and

unique ways entrepreneurs adapt to change and stay

viable during adversity.

(1) Recognize when to Pivot

“We took immediate action in 2020 to be proactive around

safe work practices, such as PPE and a combination of

telework.”

“The business did lose out on revenue due to the stay home

order but I am now currently writing a book.”

Entrepreneurs have an innate ability to recognize an

opportunity (Kirzner 1973) and thus, a question surrounding

entrepreneurship research is why entrepreneurs

recognize opportunities that non-entrepreneurs fail

to see (Dyer, Gregerson, & Christensen, 2008). Popular

explanations for their unique opportunity recognition

may include personality, cognitive, or social network

differences. In turn, these thought processes are linked

to one’s perceptions of risk-taking, tolerance for ambiguity,

or one’s locus of control (meaning one’s view on

whether or not they have the ability to influence a situation)

for example.

With feedback from our sample and with the support of

other entrepreneurial research (Dyer et al., 2008), both

entrepreneurs and organizational leaders recognize

opportunities for innovation by frequently asking questions

that may challenge the status quo. This includes

questions regarding what the future may hold. Second,

entrepreneurs can explore these questions and/or their

environment by creating hypotheses and testing them

along the way. Third, through the engagement of idea

networking, they can test their hypotheses on a network

of individuals with differing perspectives, thus learning

from others as well. Finally, engaging in these processes

leads to pattern recognition and thus, the discovery of

new ideas.

(2) Increase Resilience

“I opted to use <a> business coaching program to stay

connected to more people during the pandemic and

it has been a wonderful thing both for learning online

marketing gaps I knew I needed to fill and in helping to

keep a vibrant tribe.”

“I embarked upon my venture a few weeks prior to COVID.

COVID made things a lot more difficult – specifically,

acquiring financing, and solidifying client retention.

COVID also put an additional strain on family income

because it shut my spouse’s business down for several

months. However, it also gave my business somewhat

of a competitive advantage because our skillset could

manage virtual interpersonal relations better than many

of our competitors.”

Resilience is described as “The capacity of a system

to survive, adapt and grow in the face of change and

uncertainty” (Fiksel, 2006, p. 21). The COVID-19 pandemic

not only disrupted the entire economy, but had a

significant impact on peoples’ personal and professional

lives. It is within this context that the heightened levels

of resilience often found in entrepreneurs (Bullough et

al., 2014) allowed them to shift and reinvent (their businesses)

during this time. For example, regardless of a

positive, negative, or generally significant event – the

interpretation, coping mechanisms, and other individual

differences (e.g., resilience, stress mindset) of an entrepreneur

influences the viability of their venture, and

further, the long-term effects of their business. Events

– such as the pandemic – also determines their view on

needed resources, which largely influences their wellbeing

and start-up persistence (Marshall, Meek, Swab,

& Markin, 2020).

These heightened levels of resilience “maintain relatively

stable, healthy levels of psychological and emotional

functioning over time” (Corner, Singh, & Pavlovich, 2017,

p. 688), though active steps can be taken to increase

resilience. According to psychologist Susan Kobasa,

resilience stems from first, viewing difficulty as a challenge

rather than a paralyzing event, second, staying

committed to your life and goals (this includes work as

well as relationships, spiritual beliefs, etc.), and third,

focusing on those events or situations that you have

control over, which in turn leads to greater empowerment

and confidence.

(3) Learn from the Past to Shine Light on Future Directions

“I have learned that remote work can be positive.”

“I convinced my mom it would be a good idea to close

down our showroom and strictly do online sales from

our warehouse. This was one of the best decisions we’ve

made and have seen a large increase in revenue since

going to strictly online sales.”

Both opportunity recognition and heightened resilience

further allows for a greater ability to learn. Combining

these mindsets and learning from the past increases the

ability to cope with failure (Singh, Corner, & Pavlovich,

2007), along with the emotions and cognitive processing

in which to do so (Byrne & Shepherd, 2015). Entrepreneurs

perceive heightened learning, such as the ability

to transfer knowledge from one venture to the next,

when they first, choose to attribute the failure to internal

causes and second, start a second venture quickly after

failure (Yamakawa & Cardon, 2015). Therefore, reflecting

on past controllable steps, combined with a rapid view

on how to move forward, increases both learning and

a look into ways to move forward.

Final Thoughts

Discussions on the mindset of entrepreneurs may not

initially appear relevant to those in a large organization

or in a corporate role. However, according to a

study led by the Boston Consulting Group, one in three

companies requires a turnaround, at any point in time.

In this regard, organizations, and those entrepreneurs

or leaders, must be frequently prepared for changes

to their operations or strategies. We encourage these

considerations in not only the pandemic, but also during

general organizational change.

References

Ambepitiya, K. R. (2016). The role of women entrepreneurs in establishing

sustainable development in developing nations. World Review

of Business Research, 6(1), 161-178.

Boesch, D., & Phadke, S. (2021). When women lose all the jobs:

Essential actions for a gender-equitable recovery. Center for American

Progress.

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/

reports/2021/02/01/495209/women-lose-jobs-essential-actions-genderequitable-

recovery/

Byrne, O., & Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Different strokes for different

folks: Entrepreneurial narratives of emotion, cognition, and making

sense of business failure. Entrepreneurship

Theory and Practice, 39(2), 375-405.

Corner, P. D., Singh, S., & Pavlovich, K. (2017). Entrepreneurial resilience

and venture failure.

International Small Business Journal, 35(6), 687-708.

Ellingrud, K., & Segal, L.H. (2021). COVID-19 has driven millions of

women out of the workforce. Here’s how to help them come back.

Fortune. https://fortune.com/2021/02/13/covid-19-women-workforceunemployment-

gender-gap-recovery/

Ewing-Nelson, C. (2021). All of the jobs lost in December were

women’s jobs. Washington: National Women’s Law Center. https://nwlc.

org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/December-Jobs-Day.pdf

Dyer, J. H., Gregersen, H. B., & Christensen, C. (2008). Entrepreneur

behaviors, opportunity recognition, and the origins of innovative

ventures. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(4), 317-338.

Fiksel, J. (2006). Sustainability and resilience: toward a systems

approach. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 2(2), 14-21.

Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Li, C., Murad, M., Shahzad, F., Khan, M. A. S., Ashraf, S. F., & Dogbe, C.

S. K. (2020).

Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of

entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive

personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1611.

Marshall, D. R., Meek, W. R., Swab, R. G., & Markin, E. (2020). Access

to resources and entrepreneurial well-being: A self-efficacy approach.

Journal of Business Research, 120, 203-212.

Neneh, B. N. (2019). From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior:

The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. Journal of

Vocational Behavior, 112, 311-324.

Patil, P., & Deshpande, Y. (2018). Women entrepreneurship: a road

ahead. International Journal of Economics, Business, and Entrepreneurship

(IJEBE), 1(1).

Singh, S., Corner, P., & Pavlovich, K. (2007). Coping with entrepreneurial

failure. Journal of Management & Organization, 13(4), 331-344.

Yamakawa, Y., & Cardon, M. S. (2015). Causal ascriptions and perceived

learning fromentrepreneurial failure. Small Business Economics,

44(4), 797-820.