Nicola Daniel

Senior Advisor to the Center for Financial Policy

at the University of Maryland’s RH Smith School of Business

Reining in the darker side of big tech companies has

been the battle cry of many economists, legislators, and

data privacy experts for over a decade. Why? Because big

tech’s scale and global reach have evolved to the point

where they undermine, if unintentionally, the foundation

of free markets and democratic institutions with their

market power and political advertising. Policymakers,

including Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Romer,

think the U.S. needs to rewrite economic policy for the

big tech era.

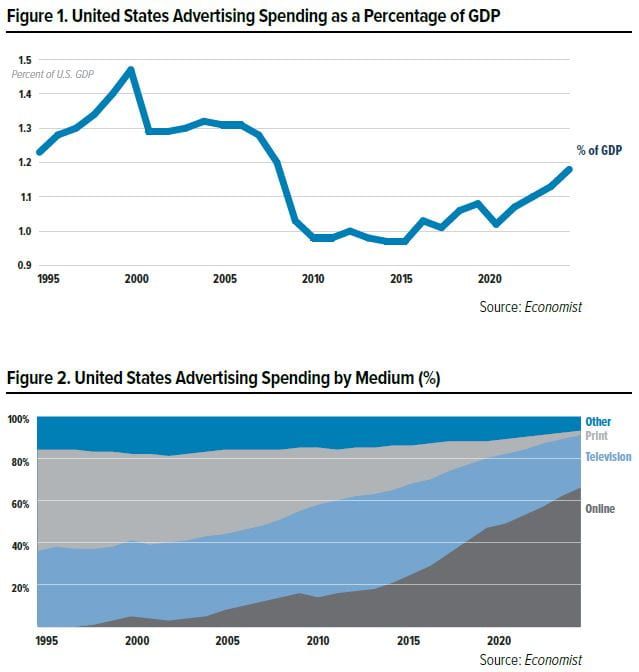

Romer’s argument for taxing Facebook and similar companies

rests on the fact that they drive their business

through algorithms that increase user engagement and

revenues by actively encouraging anger and disagreements,

so they are manipulating users “in ways that

they don’t fully understand.” This is not how markets

usually work. As Romer explains, “When economists

defend the market, we have this very simple idea in

mind, where I as a buyer give something and get some

good back.” That doesn’t happen in this new market for

digital services, in which advertising becomes a “hidden

method of capturing compensation for these firms.”

Inspired by Paul Romer’s op-ed on digital taxation in

the New York Times, Maryland State Senate President

Bill Ferguson pushed through the first digital advertising

tax in the U.S. in February 2021. The tax runs up to

10% on revenues companies receive from selling digital

ads that target Maryland IP addresses. It defines digital

advertising as services delivered on any type of software,

website, or application that a person can access on a

device. These include banner advertising, search engine

advertising, and other comparable advertising services.

Such ads tailor content based on users’ demographics

and browsing history.

Firms with less than $100 million in annual global digital

ad revenue are exempt from the Maryland tax. This

high threshold is designed to target the largest internet

companies, such as Google, Twitter, and Facebook, which

account for roughly 59% of the $130 billion digital ad

revenue market in the U.S., according to research firm

eMarketer. The tax is projected to yield up to $250 million

annually and was enacted just one week after legislators

amended the state sales tax to include “digital products”

and software as a service (SaaS).1

For Maryland small businesses, residents, and the state’s

budget, this tax makes sense, as it helps to level the

playing field between digital behemoths and smaller

companies. There are four core reasons legislators pushed

the new digital advertising tax. First, a digital tax seeks

to remedy the problem of jurisdictional tax arbitrage,

which results from companies profiting from differences

in systems of taxation. Second, it addresses the

fact that generating profit from gargantuan data caches

incentivizes companies to invade consumers’ privacy

in unprecedented ways. Third, it replaces tax revenues

lost from other sources. Finally, it encourages healthy

competition and punishes monopolies.

1 The new law defines a digital product as “a product that is obtained

electronically by the buyer or delivered by means other than tangible

storage media through the use of technology having electronic, digital,

magnetic, wireless, optical, electromagnetic, or similar capabilities.”

The law also adds SaaS, subscriptions, streaming services and “digital

codes” as taxable transactions.

The Logic of Digital Advertising Taxes

1. Tax Arbitrage

A 2021 report from the U.S. Treasury notes that “although

US companies are the most profitable in the world, the

U.S. collects less in corporate tax revenues as a share of

GDP than almost any advanced economy” at 1% of U.S.

GDP versus 3.1% of Organization of Economic Cooperation

and Development (OECD) country GDP. Regulators

in Europe have been less forgiving of tax arbitrage than

the U.S. In one case, Apple, the world’s largest company

by market capitalization, was presented with a $15.2

billion tax bill after the European Commission ruled

that Apple’s deal with Irish tax authorities constituted

illegal state aid. The commission showed that the deal

allowed Apple to pay a maximum tax rate of just 1%.

In 2014, the tech firm paid tax at a rate of only 0.005%.

The usual corporate tax rate in Ireland is 12.5%.

Google points out that its advertising sales do not take

place in a specific country, but via an auction algorithm

that is operated by algorithms whose physical location

is undefined. Hence, online advertising should not be

taxed by jurisdiction, according to Google’s argument.

The Maryland tax refutes this logic by linking advertising

directly to the IP addresses of Maryland consumers.

IP addresses are not a foolproof method of locational

identification, as critics have argued. Nonetheless, digital

ad taxes significantly curtail the ability for corporations

to engage in jurisdictional tax arbitrage.

2. Data Privacy

A digital advertising tax recognizes that companies with

massive data caches like Google, benefit financially

from the volume of individual consumer data without

economically compensating the data subject. The digital

tax thus represents the interests of Maryland residents

who provide that digital data.

Big tech’s incursion into consumer privacy has been welldocumented

in books including The Age of Surveillance

Capitalism and An Ugly Truth, a 2021 book describing

Facebook’s internal drift toward greater invasiveness

based on the profit motive.

The digital tax also responds to the federal government’s

failure to regulate consumer data privacy. The

European Union (EU) has strictly protected consumer

data privacy since 2018 through the Global Data Privacy

Regulation (GDPR).

In contrast, U.S. regulators ineffectively encouraged

companies to self-regulate. When the Federal Trade

Commission (FTC) fined Facebook $5 billion for the

Cambridge Analytica data privacy breach in April 2019,

Facebook’s stock price soared because the fine was

negligible compared to what regulators might have

levied. Since then, Facebook broke its pledge to the FTC

to keep barriers between its Instagram and WhatsApp

applications, allowing it to glean more data on its users.

The GDPR grants consumers in Europe the right to

obtain information about the data companies store on

them, as well as the right to have their data deleted.

More importantly, it grants individuals the right to sue

firms. In 2020, Max Schrems, an Austrian lawyer, sued

Facebook through the Irish Data Protection regulator

and prevailed. This suit nullified the Privacy Shield

agreement between the U.S. and the EU that allowed

for data transfers between companies across the Atlantic,

and it is forcing the U.S. to ensure better privacy

measures for consumers. There are currently six data

privacy laws proposed in Congress. Only two of them

allow individuals the right to sue, whereas the other four

require regulators to take offenders to court, suggesting

less enforcement due to capacity constraints.

3. Replacing Lost Tax Revenue

Maryland needs to replace income lost by the shrinking

of once-robust sources. For example, gas taxes, which

were once a major source of state government revenue,

have drastically fallen with increased electric vehicle use.

COVID-19 worsened this trend as driving plummeted

nationwide by 38% in the initial months of the pandemic.

Maryland experienced a 6% decline in gas tax revenues

in 2020. Overall, Maryland expects a $673 million tax

revenue shortfall—3% of projected revenues—in 2021.

Meanwhile, online tech giants grabbed unprecedented

market share as social distancing accelerated the shift

toward digital platforms. Google’s revenues grew by $20

billion to $181.9 billion in 2020. Its year-end net profits

as of June 2021 stood at a staggering $122.73 billion.

Similarly, Facebook’s revenues grew by $15.4 billion

to $86 billion in 2020, with net profits of $29.1 billion.

The annual $250 million projected tax revenue boost

from the digital advertising tax goes a long way toward

plugging Maryland’s COVID-related shortfall while

scarcely affecting the profit margins of digital giants.

4. Discouraging Monopoly

Finally, the digital tax provides incentives for healthy

market competition from smaller companies because

the more advertising revenue a firm collects, the higher

its tax rate. If a firm splits itself, e.g., if Facebook were to

spin off Instagram, the total tax bill for the two firms as

separate entities would be smaller. These higher taxes

for larger entities also discourage the kind of growth

by acquisition that drives digital giants to acquire their

potential competitors only to kill them.

Firms seeking to avoid the tax can opt for a subscription

revenue model. Subscriptions conform to a more

traditional economic framework in which consumers pay

something to get access to something valuable and the

balance of supply and demand determines the market

price. The New York Times, for example, switched from

an ad-only revenue stream to a subscription-driven

revenue stream with resounding success. Today, The

New York Times is financially healthy and dominates

online news searches.

Global Digital Tax Trends

Will Maryland be joined by other states in imposing a

digital tax? Or will it be isolated and face pressure that

may force it to end this tax?

Maryland’s digital ad tax is part of a much larger national

and global trend. As of March 2021, 26 European countries

imposed unilateral digital taxes on services like

software subscriptions, video streaming, and audiobooks.

They targeted firms that have many users in Europe and

yet pay few taxes there. The U.S. protested, claiming that

the policy would disproportionately affect U.S.-based

tech companies.

The European taxes led to negotiations, spearheaded

by the OECD and the EU, seeking to harmonize digital

taxation. The OECD has led discussions among 137

jurisdictions to establish rules about where taxes should

be paid and how profits should be allocated. Because

U.S. firms are disproportionately affected by such taxes,

U.S. regulators have increasingly participated in discussions.

The negotiations have driven economic research

that has led to a greater convergence of attitudes toward

digital taxation between the U.S. and OECD countries.

Looking Ahead

Domestic legal challenges to Maryland’s digital tax

have surfaced. In February 2021, the U.S. Chamber of

Commerce filed a suit against Maryland to challenge

the digital advertising tax, arguing that it violates the

federal Internet Tax Freedom Act. Other plaintiffs have

followed. These challenges are likely to meet with some

success and will require modifications to the existing

law. As a result, the Maryland General Assembly passed

an emergency bill to delay the digital tax’s implementation

to 2022. However, the U.S. Senate testimony of

former Facebook employee Frances Haugen in October

2021 added fuel to the drive to take regulatory action

against the larger digital platforms on multiple fronts

and may well bolster the popularity of digital taxes.

Many states—including Texas, West Virginia, Massachusetts,

and New York—are following Maryland’s lead in

introducing digital tax legislation. The digital tax trend

is not likely to abate soon.

References

“Once Tech’s Favorite Economist, Now a Thorn in Its Side,” The New

York Times (May 20, 2021).

“Taxing digital advertising could help break up big tech,” MIT Technology

Review (June 14, 2021).

“Opinion | A Tax That Could Fix Big Tech,” The New York Times (May

5, 2019).

“Duopoly still rules the global digital ad market, but Alibaba and

Amazon are on the prowl,” Insider Intelligence Trends, Forecasts &

Statistics (May 10, 2021).

MadeInAmericaTaxPlan_Report.pdf (treasury.gov). See also “Trends

and Proposals for Corporate Tax Revenue,“ Congressional Research

Service, August 27, 2021.

Apple ordered to pay €13bn after EU rules Ireland broke state aid

laws | Tax avoidance | The Guardian.

Zuboff, Shoshanna (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. New

York, Hachette Book Group.

Frenkel, S. and C. Kang (2021). An Ugly Truth. New York, Harper

Collins, pp. 226.

“FTC Imposes $5 Billion Penalty and Sweeping New Privacy Restrictions

on Facebook,” Federal Trade Commission (July, 2019).

“Amazon fined record $887 million over EU privacy violations,” The

Verge (July 30, 2021).

“Gas Tax Revenue to Decline as Traffic Drops 38 Percent,” Tax Foundation.

org (March 31, 2021).

Motor Fuel Tax and Motor Carrier Tax IFTA Annual Report (marylandtaxes.

gov).

States Grappling With Hit to Tax Collections | Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities (cbpp.org).

source: Statista.com.

The nations include: Argentina, Austria, Costa Rica, Germany, Greece,

Hungary, India, Indonesia, Italy, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria,

Pakistan, Paraguay, Poland, Sierra Leone, Spain, Taiwan, Tunisia,

Turkey, United Kingdom, Uruguay, Vietnam, Zimbabwe. Source:

americanactionforum.org.

“Maryland To Delay Controversial Digital Advertising Tax As The

Lawsuits Keep Coming,” Forbes (April 17, 2021).