Michaël Dewally, Ph.D.

Professor in the Department of Finance at Towson University

Yingying Shao, Ph.D., CFA

Professor in the Department of Finance at Towson University

The Program

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted our daily lives and interrupted business to such a large scale that many enterprises faced imminent failure. To protect the fabric of the American business landscape, the U.S. Congress swiftly passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) on March 27, 2020. Among its provisions, the CARES Act allocated $953 billion to the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). The PPP’s purpose was to fund payroll costs for small businesses as well as interest on mortgages, rent, and utilities. Eligible businesses applied for the loans to private lenders. PPP loans have a provision of forgiveness for the amount of the loan spent on payroll to the extent that employees were kept or rehired. For issuing banks, the financial risks are minimal. The loans are forgivable and the sponsor is the Small Business Administration (SBA), an entity with which banks routinely work in assisting local enterprises. Additionally, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) recognized that PPP loans have no impact on regulatory capital because they bear no credit or market risks due to the government guarantees. PPP loans therefore only carry operational costs since they require additional loan officers to process applications, speed up lending and deal with exposure to new clients. This was an unprecedented effort.

The program proved swiftly successful. Businesses of all sizes applied for funding and some applied for a second draw for additional funding. The loans carry a one percent interest rate. As of the PPP Report through 9/12/2021, the program approved 11,496,362 loans nationwide for a total dollar amount of $792,753,837,209 funneled through 5,467 lenders. As the economy has recovered albeit at a slow pace, many businesses have initiated their application for forgiveness. The 6,739,872 applications for forgiveness represent 69.3% of the dollar borrowed and the SBA has approved 96.5% of these applications.

The Program in Maryland

COVID-19 Impact

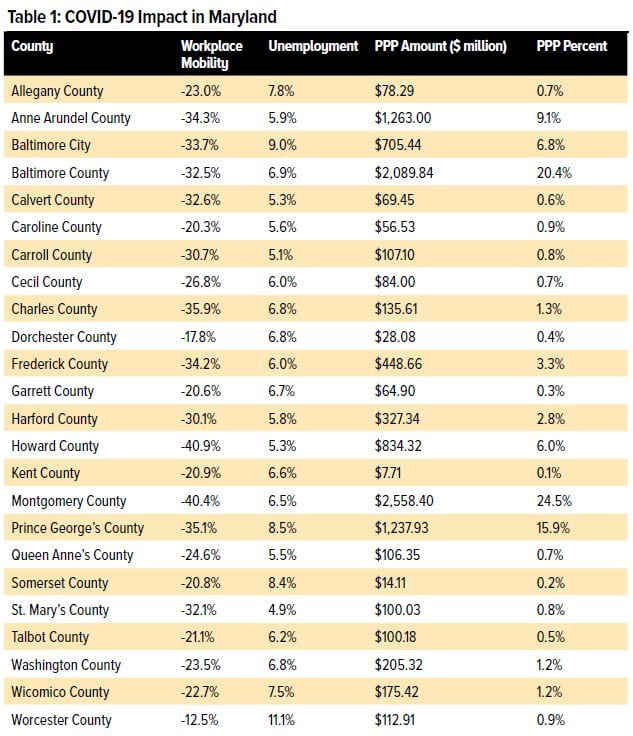

To measure where PPP loans were disbursed in Maryland, we retrieve information on several aspects of the COVID- 19 crisis. We collect data from Google, the Maryland Department of Labor and the SBA. From Google we collect information on Mobility1 during the crisis, starting from the second quarter of 2020. Google’s Community Mobility Report tracks how communities are moving around differently due to COVID-19. Due to different local responses to the crisis, the local interruption of business and economic activity varied across the nation and within states. Google’s Mobility measures tracked “movement trends over time by geography across different categories of places such as retail and recreation, groceries and pharmacies, parks, transit stations, workplaces, and residential.”

We select the Workplace mobility measure to represent how strict or loose the lockdown restrictions were at the local level and how these rules were followed. In Maryland, workplace mobility dropped an average of 29%, in line with the nationwide average. However, some areas saw drops in excess of 40% in Howard and Montgomery counties, and both Baltimore City and Baltimore County experienced drops of about 33%. In contrast, workplace mobility dropped the least in Worcester County with a decline of only 13%. We present these measures in Table 1. We see that the most affected areas are located in the Baltimore – Washington DC corridor while the counties most East and West were the least affected. These same counties experienced the lowest reported cases of COVID-19.

Declines in workplace mobility, however, combine the influences of both decreased employment and the ability to work remotely, the latter of which provides job security and protects employment during the pandemic. To know where unemployment spiked during the crisis, we collect unemployment rates across the state from the Maryland Department of Labor. We find that the unemployment rate was the highest in Worcester County (11.1%) followed by Baltimore City (8.9%) and Prince George’s (8.5%) while St. Mary’s County experienced the lowest unemployment rate (4.9%).

PPP Location

Using the data from the SBA from August 2020, we track the first round of the PPP for funds that hit the coffers of Maryland businesses at the height of the crisis.

At the top of the list comes Montgomery county with $2.5 billion, followed by Baltimore City with $2.0 billion, Anne Arundel with $1.3 billion and Prince George’s with $1.20 billion. In contrast, Kent County businesses only received $8 million from the program. We transform the information to show the percentage of PPP loans received in each county. Businesses in Montgomery County received 24.5% of all PPP dollars in Maryland, while businesses in Kent County received the least at 0.1%.

The evidence presented suggests that the distribution of PPP funds reconciled with the intention of the government initiatives. It was in those areas the most impacted by COVID-19 and the ensuing restrictions that PPP lending was the most in demand. The injection of rescuing funds no doubt have helped local businesses sustain their employment and provided financial securities to the workforce.

PPP Recipients

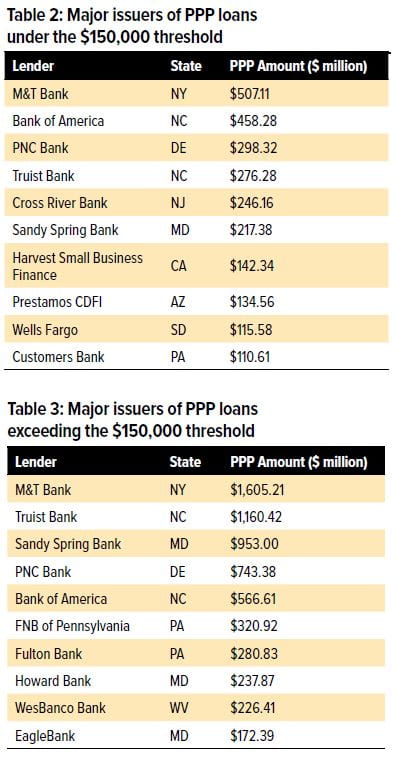

The SBA data is released in two sets: one for small loans under $150,000 and one for large loans in excess of $150,000 up to the limit of $10 million set by the program. The total amount a business can request cannot exceed 2.5 times the average monthly payroll costs for 2019.

In Maryland, under the $150,000 loan threshold, there were 168,981 loans approved for businesses that reported an average of 4 employees. This amounted to $4.8 billion in total loans and 664,764 jobs sustained by the program. There were also 18,918 large loans each exceeding $150,000, representing additional total loans of $10 billion. These larger businesses employed an average of 50 employees, for 944,595 additional employees supported by the program.

PPP Forgiveness

Of this total $14.8 billion, a full $7 billion, or 47%, had already been forgiven by September 2021. The forgiveness rate is larger for larger businesses (51%) than it is for smaller businesses (40%). This difference reflects the burden the early forgiveness application process placed on smaller businesses. The SBA adjusted its forgiveness application to facilitate the sharing of information between the borrower, the lender and the SBA itself.

PPP Lenders

There have been multiple runs of PPP loan issuance since its first launch. As much as the nation saw the entire financial sector participate in the program to help funnel funds where needs were, so did Maryland. The SBA records 768 different nation-wide lenders issuing loans to Maryland businesses, from 1st Choice Credit Union in Atlanta, Georgia to Zions Bank in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Table 2 records the list of the top ten lending banks to smaller businesses in Maryland, providing loans under $150,000, throughout the entire PPP including 2021. The list shows banks ranging far and wide from some of the largest banks in the country (M&T Bank, Bank of America, PNC, and Wells Fargo) to smaller banks active during the PPP rollout. For example, Prestamos, a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) out of Arizona and the lending division of Chicanos Por La Causa, a Community Development Corporation (CDC), approved, just in 2021, 494,415 PPP loans for a total $7.7 billion nationwide. In Maryland, Prestamos approved $134 million to small businesses. The only bank locally headquartered in Maryland in the top ten list is Sandy Spring Bank.

The top ten lenders to larger businesses in Maryland are listed in Table 3. Some institutions appear to carry the same role in actively underwriting the PPP loans. M&T Bank leads their peers again and we see that for all Maryland businesses, M&T Bank issued in total over $2 billion in PPP funding while Sandy Spring Bank provided over $1.1 billion in PPP loans. Research by Li and Strahan (2021)2 shows that, despite their lack of credit risk, banks were more likely to issue PPP loans to businesses with whom they had prior experience, meaning PPP loans were issued to businesses with an established relationship with the issuing bank. Their findings suggest “a new benefit of bank relationships: [..] access [to] government-subsidized lending.” In Table 3, we find more regional lenders and larger loan issuance, compared to the list in Table 2. This is in line with Li and Strahan’s findings on the importance of relationship lending.

Focusing on the largest lenders obfuscates other strong supporters like Harbor Bank, as reported in The Baltimore Sun in August 20213. Harbor Bank opened for business in 1982 and has since raised its assets from $2 million to $321 million in 2020. During the crisis, in Maryland alone, Harbor Bank provided over $46 million in PPP loans, or over 14% of its assets. Harbor issued 426 loans under $150,000 for $13.4 million, and an additional 70 loans over $150,000 for $32.7 million. The Sun article reports that Harbor Bank tasked its “employees [to go] out of their way to help qualified business owners, regardless of whether they were Harbor Bank customers.” Li and Strahan (2021) report that “bank PPP supply [..] alleviates increases in unemployment.” The combined efforts of Harbor Bank, other Maryland lenders and out of state lenders allowed Marylanders to retain their employment during the crisis and prepared Maryland for a speedier recovery.

References

1 https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/

2 Li, L. and P.E. Strahan (2021). Who supplies PPP Loans (and does it matter)? Banks, relationships and the COVID Crisis. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis Accepted manuscript.

3 A go-to resource during the pandemic – Maryland’s only Black-owned and -managed commercial bank stepped up – Newsmaker, August 3, 2021, Sun, The (Baltimore, MD), Billy Jean Louis, p. 3.