Bradford Muir

Supervisor at Vallit Advisors

The COVID-19 pandemic has uniquely challenged

businesses; no business model or industry appears

to be immune. However, situations vary. Some

companies have been forced to adapt to avoid shuttering,

while others are riding out state-mandated

closures using cash on hand and Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP) loans. As a result, the effects of

COVID-19 on business valuations of privately held

companies can vary dramatically.

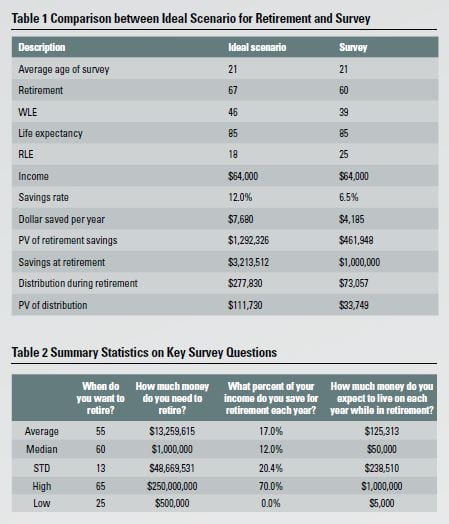

The pandemic has notably affected business valuations

through the discount rate used in the income approach

to valuation, in which projected future cash flows are

discounted to present value using a discount rate. This

article discusses the significance for valuations of privately

held businesses of (1) volatility and risk, (2) the

build-up method for determining the discount rate, and

(3) the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on risk and

the equity discount rate for privately held businesses.

Volatility and Risk in the Global Pandemic

Volatility and risk matter because they affect what

buyers will pay for privately held businesses. Since the

pandemic’s start, U.S. equity markets have experienced

significant changes in volatility that are at least partly

tied to people’s perception of risk in those markets.

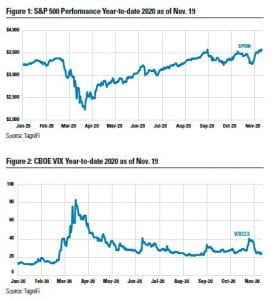

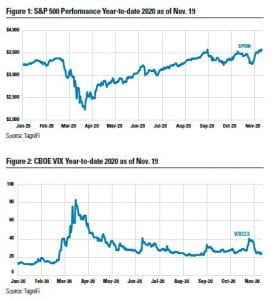

U.S. equities, as measured by the S&P 500 index, fell

more than 33% in the one-month period from February

20 to March 20 (Figure 1). However, they have

recouped these losses, eclipsing their late-February

high in late August.1

In addition, equity market volatility, which acts as a

gauge of investor sentiment, has hit levels of volatility

unknown since the 2007–2008 financial crisis. As shown

in Figure 2, the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) soared

from 15.6 on February 20 to a record high of 82.7

less than 30 days later on March 16, due to the rapid,

unchecked spread of the coronavirus. Values greater

than 30 for the VIX, which represents the implied volatility

of 30-day options on the S&P 500, are generally

associated with a large amount of volatility because

of investor fear or uncertainty, while values below 20

generally correspond to less stressful, even complacent,

market conditions.

Despite efforts by the Federal Reserve and Congress to

stabilize equity markets, the VIX remained significantly

above pre-pandemic levels throughout the summer.

Volatility has remained high over the 60-day period

ended November 19 as the United States and many

European nations have seen a resurgence in new coronavirus

cases.

Risk is associated with volatility. The tighter the probability

distribution of returns for an investment in

the existing economic conditions, the lower the risk

profile of the investment. In other words, risk can be

defined as, “the degree of uncertainty (or lack thereof)

of achieving future expectations at the times and in

the amounts expected.”2

In business valuation, risk is evaluated, quantified, and

accounted for in the discount rate. A discount rate is a

rate of return used to convert a monetary sum, payable

or receivable in the future, into its present value.3 The discount

rate is equal to the “cost of capital,” the expected

rate of return that the market requires to attract funds

to a particular investment.4 Thus, the cost of capital

is based on the principle of substitution, in that it is

equal to the return that could be earned on alternative

investments with a similar level of risk.

Other terms used interchangeably to describe the cost

of capital include:

- Rate of return

- Required rate of return

- Cost of equity capital

- Weighted average cost of capital

- Alternative cost of capital

- Discount rate

- Hurdle rate

Risk and return are positively correlated. The greater the

perceived risk of an investment, the higher the required

rate of return an investor would demand from the

purchase of the investment. Accordingly, the discount

rate and value are negatively correlated. In other words,

when perceived risk and the discount rate increase,

the value of the company decreases, all else being held

constant. It is important to note that the relationship

between risk and value is nonlinear (e.g., a percentage

change in the discount rate does not result in an equal

percentage change in value).

The Build-Up Method for Determining the Discount Rate

For business valuations, two types of discount valuations

are relevant for investors who provide capital in

the form of equity or debt. They are the equity discount

rate and the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

As stated above, the equity discount rate represents the

required rate of return for an equity investor to invest in

the business, whereas the WACC considers the return

required by both equity and debt investors.

The build-up method is one of the methods most widely

used by valuation analysts to determine the cost of

equity. As the name implies, the build-up method is an

equity discount rate estimated as the sum of multiple

rates of return and risk premia, expressed in percentages

as follows:

Cost of Equity = RFR + ERP + SRP + SCRP

RFR is the risk-free rate; ERP, equity risk premium;

SRP, size risk premium; and SCRP, specific company

risk premium.

Effects of COVID-19 on the Discount Rate’s Components

As of November 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic

has significantly affected business valuations through its

impact on discount rates using the income approach,

in which projected future cash flows are discounted

or capitalized back to present value using a discount

rate (or a capitalization rate) to account for the risk of

achieving those projected cash flows.5 By their nature,

discount rates are tied closely to local, national, and

global economic performance, and therefore fluctuate

with the market.

When determining the cost of equity, the build-up

method considers and aggregates multiple building

blocks (RFR, ERP, SRP, and SCRP). With the spread of

COVID-19, most of these building blocks have fluctuated.

Risk-free rates are currently lower as a result of the

Federal Reserve maintaining a low interest rate environment.

On the other hand, the equity risk premium has

increased as a result of general economic instability.

Additionally, as companies battle an economic downturn

and potentially going out of business as a result

of COVID-19, the SCRP can also increase as a result

of the greater risk of the company not achieving its

projections. We discuss the effects of the pandemic on

each component below.

Risk-Free Rate

The RFR is the rate of return available on

investments free of default risk. The most

appropriate proxy for the RFR is the yield on a

30-year U.S. Treasury bond, 10 years into its life

cycle with 20 years remaining.6 Valuation analysts

typically get cost of equity data including RFR

guidance from Duff & Phelps.

When equity markets tumble, as they did at the beginning

of the pandemic, an RFR-lowering “flight to quality”

typically follows as investors seek the perceived safety

of Treasuries. If a valuation analyst were to use the spot

yield in the build-up method under these conditions,

the result would be a lower equity discount rate and

cost of capital, all other components held the same,

rather than reflecting the increased risk associated with

an uncertain economic environment. In a situation

like this, some valuation analysts may choose to use a

normalized RFR to account for inflation and short-term

effects on interest rates.7 A normalized RFR is typically

estimated by averaging yields to maturity on long-term

government bonds over several periods.

As a result of the pandemic, in early July, Duff & Phelps

lowered its normalized U.S. RFR from 3.0% to 2.5%

for estimating discount rates in valuations after June

30, 2020.8

Equity Risk Premium

The expected returns on equity are much less certain

than on U.S. Treasuries, so they are riskier than the

interest and maturity payments on U.S. Treasury obligations.

Accordingly, in exchange for an increase in risk,

investors demand higher returns for equity investments.

The ERP reflects this additional risk.

In late March 2020, Duff & Phelps increased its U.S.

ERP from 5.0% to 6.0%. In doing so, it cited some

of the pandemic’s effects on U.S. businesses, including

supply chain disruptions, job losses, business closures,

and collapsing equity markets.9 ERP is a critical component

of the build-up method of determining the equity

discount rate, and this suggested change (for developing

discount rates as of March 25, 2020, and forward)

reflects the severity of the current crisis. Keep in mind

that the discount rate has an inverse relationship with

value. As the discount rate increases, all other things

remaining constant, the value of the business decreases.

Professor Aswath Damodaran suggests using a COVIDadjusted

ERP, which he estimates monthly based on an

expected earnings analysis. His COVID-adjusted ERP

has ranged from 6.02% in April 2020 to the current

ERP of 5.02% for November 2020. Damodaran, a

professor of business valuation and corporate finance

at New York University’s Stern School of Business,

has published numerous articles and books on the

equity discount rate and the components of the buildup

method. Damodaran maintains a website and a

blog, which he uses as a platform to update valuation

analysts on the perceived effects of COVID-19 on the

financial marketplace.10

Simply adjusting risk percentages for every valuation

is not enough to account for the effects of COVID-

19.11 Damodaran says that “It is almost impossible

to adjust for [COVID-19] in discount rates and it is

therefore imperative that you make judgments about

the likelihood that your company will not make it, and

this probability will be higher for smaller companies,

young companies, and more indebted companies.”12

Amid great uncertainty, Damodaran suggests that valuation

analysts cannot simply rely on higher discount

rates to account for COVID-19. Instead, experts must

apply critical judgment more than ever before, to ensure

that all risk factors are considered in developing the

equity discount rate.

Size Premium

Small capitalization stocks are considered riskier investments

than large capitalization stocks. As a result,

investors require additional return in exchange for

the added risk of investing in small-cap stocks. The

SP represents the additional return expected by an

investor in the stock of a small-cap company over that

of an otherwise comparable investment in a larger

company. This also applies to investments in privately

held companies.

Little consensus exists among valuation analysts about

the effects of COVID-19 on the size premium. Generally,

smaller companies have been hit worse than large

companies with cash on the balance sheet to weather

the short-term cash crunch. Time will tell whether

small companies are disproportionately affected by the

pandemic, which would warrant an increase in the SP. If

increases are needed, we expect to see higher observed

SP in business valuations in the future, depending on

the course of the virus and the country’s response.

Specific Company Risk Premium

An SCRP is often appropriate to reflect unsystematic

risk factors, which refers to risks that are specific to the

company relative to the market as a whole. This is an

area where the judgment of the valuation analyst comes

into play. Examples of unsystematic risk could include

the financial history and current financial condition

of the entity, depth of management, key-person risk,

customer concentration, and competition.

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected businesses

in some industries, while leaving others relatively

unscathed or even benefiting from the pandemic. Projection

risk—the risk of a company not achieving its

projections—can either be accounted for by adjusting

a company’s discrete projected cash flows to include a

probability weighting or other applicable adjustment,

or by including an additional risk consideration in the

SCRP component of the build-up method of determining

the discount rate.

The ability of a company to pivot and to take advantage

of opportunities has proven critical during the pandemic.

For example, in the food service industry, restaurants

that have successfully and efficiently shifted from dine-in

to curbside pickup and delivery have generally fared

better than restaurants tied to the dine-in experience.

Consumer demand for dine-in restaurants may not

rebound until after widespread COVID-19 vaccinations,

or even later, which translates to an additional level of

uncertainty for their projected cash flows. Companies

that have retooled or adapted their business model have

generally outperformed and may not have suffered

financially as a result of the pandemic, so a change in

SCRP may not be necessary.

The pandemic forces the valuation analyst to consider

factors such as state and local regulations and their

effects on business operations and risk. For example,

a brick-and-mortar business with locations throughout

the country might be better geographically diversified

when some locations are forced to close, but others can

remain open. The analyst must become familiar with

the dynamic regulatory environment in each location.

Cost of Equity and WACC

The sum of the above components of the build-up

method is the equity discount rate. The estimation of

the WACC considers the equity discount rate, the cost

of debt, and the capital structure. The cost of debt

is based on the company’s outstanding debt obligations

and consideration of market conditions.13 The

capital structure represents the proportion of equity

and debt for the company, which is applied to the

equity discount rate and cost of debt, the sum of which

represents the WACC.

For the foreseeable future, the risk associated with the

uncertainty and volatility of the COVID-19 pandemic

will continue to be a critical factor in business valuations.

In the current environment, the valuation analyst

must consider many more factors with a higher level

of scrutiny when determining an equity discount rate.

Analysts must critically examine the outlook for the

company being valued; its adaptability; the industry;

customer relationships; local, state, and federal regulations

and COVID restrictions; and dozens of other

dynamic factors. Because accounting for the effects of

a modern-day global pandemic is uncharted territory,

analysts can only speculate about the projected effects

that a vaccine or a global reduction in case counts and

deaths will have on risk and the equity discount rate.

Endnotes

1As of November 19, 2020.

2David Laro and Shannon P. Pratt, Business Valuation and Federal

Taxes: Procedure, Law, and Perspective, 2nd ed., Chapter 12.

3BVR’s Glossary of Business Valuation Terms 2010, Business Valuation Resources, p. 6, https://sub.bvresources.com/freedownloads/

bvglossary10.pdf.

4BVR’s Glossary of Business Valuation Terms 2010, Business Valuation Resources, p. 5, https://sub.bvresources.com/freedownloads/

bvglossary10.pdf.

5The income approach includes the discounted cash flow (DCF)

method and the capitalized cash flow (CCF) method. The CCF

method may be inappropriate for companies that are experiencing

temporarily reduced revenue and profitability as a result of

COVID-19; instead, a valuation professional may choose to use the

DCF method when a company’s cash flows have been affected in

the short term by the pandemic, but they expect financial performance

to recover in the next few years.

6These rates can be obtained online from the Federal Reserve

Statistical Release H.15.

7The assumption that a normalized RFR might yield the

best estimate of the risk-free rate in times of flight to quality arose during

the 2008-2009 financial crisis. See Roger Grabowski, “Developing

the Cost of Equity Capital: Risk-free Rate and ERP during Periods

of ‘Flight to Quality,’” Business Valuation Review, Winter 2010.

8Carla Nunes and James P; Harrington, “Duff & Phelps U.S.

Normalized Risk-Free Rate Lowered from 3.0% to 2.5%, Effective

June 30, 2020,” https://www.duffandphelps.com/insights/

publications/cost-of-capital/us-normalized-risk-free-rate-loweredjune-

30-2020.

9Carla Nunes and James P; Harrington, “Duff & Phelps

Recommended U.S. Equity Risk Premium Increased from 5.0% to 6.0%

Effective March 25, 2020,” https://www.duffandphelps.com/

insights/publications/cost-of-capital/us-equity-risk-premiumincreased-

march-25-2020.

10Aswath Damodaran, Damodaran Online, http://pages.stern.nyu.

edu/~adamodar/.

11http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/; http://www.stern.nyu.

edu/~adamodar/pc/implprem/ERPbymonth.xlsx.

12Aswath Damodaran, “A Viral Market Meltdown V: Back to

Basics!” Musings on Markets, March 31, http://aswathdamodaran.

blogspot.com/2020/03/a-viral-market-meltdown-v-bailouts-and.

html

13Since the interest paid on most debt remains tax deductible

under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the interest rate applicable to

this debt is tax-affected to produce an after-tax cost of debt, see

https://www.cbh.com/guide/articles/planning-for-the-new-businessinterest-

expense-deduction-limitation/

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve

Statistical Release H.15. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/

h15/

BVR’s Glossary of Business Valuation Terms 2010, Business Valuation

Resources LLC. https://sub.bvresources.com/freedownloads/

bvglossary10.pdf

Damodaran, Aswath, Damodaran Online. http://pages.stern.nyu.

edu/~adamodar/

Damodaran, Aswath, Musings on Markets, http://aswathdamodaran.

blogspot.com/

Grabowski, Roger J., “Developing the Cost of Equity Capital:

Risk-free Rate and ERP during Periods of ‘Flight to Quality,’” Business

Valuation Review, Winter 2010.

Laro, David and Shannon P. Pratt, Business Valuation and Federal

Taxes: Procedure, Law, and Perspective, 2nd edition, Hoboken,

NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Nunes, Carla, and James P. Harrington, “Duff & Phelps Recommended

U.S. Equity Risk Premium Increased from 5.0% to 6.0%

Effective March 25, 2020,” Duff & Phelps, March 27. https://

www.duffandphelps.com/insights/publications/cost-of-capital/usequity-

risk-premium-increased-march-25-2020

Nunes, Carla, and James P. Harrington, “Duff & Phelps U.S.

Normalized Risk-Free Rate Lowered from 3.0% to 2.5%, Effective

June 30, 2020,” Duff & Phelps, July 9. https://www.duffandphelps.

com/insights/publications/cost-of-capital/us-normalized-risk-freerate-

lowered-june-30-2020

Pratt, Shannon P., and Roger J. Grabowski, Cost of Capital, 5th

edition, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

TagniFi, TagniFi Econ. https://www.tagnifi.com/