Farhan Mustafa, CFA

Head of Investment Risk Management and Head of Quantitative Investments, ClearBridge Investments

Last year’s Baltimore Business Review covered a speech

by former Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Chair Sheila

Bair in which she expressed concern over the record

level of debt among U.S. businesses. This article updates

the analysis and provides a deeper quantitative dive

into the leverage profile of S&P 500 companies. It

also considers how those profiles should factor into

stock analysis.

Federal and Corporate Debt Hits Record Levels

U.S. companies and the federal government have issued

record levels of debt in recent years, largely due to nearly

a decade of record-low interest rates. Figure 1 shows

that federal debt currently represents 136% of GDP

(blue line) and corporate debt represents 56% of the

national output (gray line), both of which are historic

highs since at least 1965.. Debt levels as of the end of

2020’s second quarter were: $10.99 trillion nonfinancial

corporate, $26.48 trillion federal, and $16.14 trillion

household and nonprofit. Each of these debt levels

represents absolute historic highs. The latest observation

for the second quarter of 2020 looks especially

dramatic due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

as U.S. GDP declined 9.5%, while federal debt increased

14.0% and corporate debt increased by 3.3%.

Figure 1 also shows an uptick in U.S. household debt to

83% of GDP (gold line) at the end of the second quarter.

However, unlike the financial crisis of 2008–2009, the

rise in consumer debt is significantly lower, which is

consistent with Ms. Bair’s observation last year that

U.S. households’ low indebtedness has been a positive

development.

As noted above, the latest increases in federal and corporate

debt in Figure 1 were worsened by the sharp

decline in GDP caused by the widespread economic

shutdown to fight the coronavirus. It would be reasonable

to see a similarly sharp decline in these ratios once

GDP rebounds in a post-pandemic world. However,

the data series were at historic highs even before the

COVID-19 pandemic-related spike, and there are no

signs of a meaningful reduction in these ratios because

most central banks and governments remain committed

to accommodative fiscal and monetary policies to

fight the economic slowdown from the coronavirus.

These aggressive policy measures are appropriate to

manage the fallout from the global pandemic. But these

accommodative monetary and fiscal policies come on

the heels of multiple years of accommodative policies

that have virtually eliminated the potency of interest

rates as a policy tool around the world. Developed

economies around the globe have been issuing negativeinterest-

rate debt for several years. As Figure 2 shows,

there is nearly $16 trillion of negative-yielding debt

outstanding as of September 30, 2020, with Japan

representing nearly one-third, and Germany and France

each representing one-sixth of the total.

Negative-yielding debt condemns bondholders to lose

money if they hold the issue to maturity. At the macroeconomic

level, central banks in Japan and Europe are

using this as a monetary policy tool to encourage banks

to lend and stimulate the economy. At the microeconomic

level, investors may tolerate negative-yielding

bonds due to anticipation of even worse returns in

other investments. For traders, negative-yielding debt

could simply be an outcome of positive momentum

in the price of these bonds, where successive trades at

higher prices are profitable as yields move further into

negative territory.

Pressure Is Building

There is a logical narrative for why U.S. corporate and

federal debt are at historic highs—both absolutely and

relative to GDP. There is also a rational explanation

for why developed economies are awash in negativeyielding

debt. However, it is unreasonable to expect

these trends to continue without a major disruption

or reversion to their long-term averages because these

dynamics come with ever-increasing risks. These trends

represent pressure building beneath the surface of an

otherwise profitable and rising market.

It is possible that large-scale fiscal spending into the

global economy’s long-term productive capacity would

generate sufficient economic productivity to pay off all

the debt, especially with such low interest rates. But what

if productivity does not support enough real economic

growth to carry the debt burden? In such a scenario, the

aggressive policy measures would result in inflationary

pressures and higher interest rates, even if we get some

nominal economic growth. It is also worth considering

more stressful scenarios, such as a crisis of confidence

in the creditworthiness of the borrowers in a modest

economic recovery, in which case the higher cost of

borrowing would likely push levered businesses into

distress or even bankruptcies. Or, what if geopolitical,

socioeconomic, or existential risks like war, income/

wealth inequality, climate change, etc., disrupt the

socioeconomic stability required to bring the global

debt load to more reasonable levels? We can present

lengthy analyses about each of these scenarios, but the

key point is there are multiple scenarios in which the

current debt regime could prove unsustainable and

result in individual company bankruptcies or even a

systemic debt crisis.

A debt crisis happens when an entity (corporate or governmental)

defaults on its loans. From Latin America’s

lost decade in the 1980s to the 2008–2009 credit crisis

in the U.S. and the European Union, there are plenty

of painful reminders of what happens when countries

cannot service their debts. A debt crisis can undermine

the stability of financial systems in the crisis-hit

country, and also spread to other countries, especially

for strategically connected economies like the European

Union and Japan. This can hit economic growth, as

well as create turmoil in global financial markets. If a

country’s debt crisis is severe enough, it could result

in a sharp economic slowdown at home that drags on

growth elsewhere.

This analysis is not meant to predict an impending

global debt crisis. The economy and the stock market

are complex adaptive systems in which agents adapt

to current conditions, and the eventual outcomes are

often very different from linear extrapolations of recent

events. Rather, the point is that highly levered agents

(companies, governments, etc.) would be at greater

risk of bankruptcies than unlevered agents in a higherrate

environment. Therefore, the rest of this article

analyzes the leverage risk of S&P 500 companies to

help identify highly levered and unlevered investment

opportunities. At the outset, it is important to note

that leverage analysis should not be the entire basis of

an investment decision, but it should be a key component

of a more comprehensive stock analysis for any

investment decision.

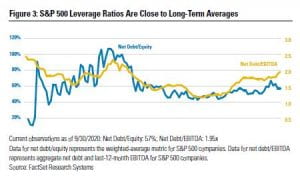

A Closer Look at U.S. Corporate Debt

Figure 3 shows leverage (net debt/equity) and debt-servicing

(net debt/EBITDA) ratios for S&P 500 companies

from 1990 to the second quarter of 2020. In terms of

overall leverage, net debt represents 57% of the equity

as of Sept. 30, 2020, which is in line with its long-term

average of about 60%. From the perspective of being

able to repay the debt, net debt represents 1.95 times

EBITDA as of Sept. 30, 2020, which is modestly above

its average of 1.69x since 1990.

On the surface, using sensible high-level metrics like

weighted-average net debt/equity and aggregate net

debt/EBITDA, S&P 500 stocks do not appear to have

elevated leverage in the aggregate. However, a breakdown

of the index constituents into the most- and

least-levered stocks presents a much different picture.

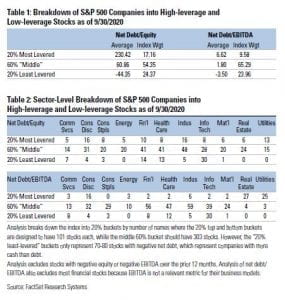

Table 1 shows the breakdown of S&P 500 companies

into the 20% most-levered stocks, the “middle” 60%,

and the 20% least-levered stocks, based on net debt/

equity and net debt/EBITDA metrics. For each metric,

the “average” column shows an unweighted average

statistic for each group and the “index weight” column

shows the percentage of index weight in each group.

Table 2 shows the sector breakdown of the stocks in

each bucket based on the net debt/equity and net debt/

EBITDA metrics.

Around one-quarter of the S&P 500 Index consists of

stocks with negative net debt/equity and net debt/EBITDA

metrics, which typically means these stocks have net cash,

or more cash than debt.1 From Table 2, we can further

see that the majority of these companies are in the information

technology sector. These companies represent a

larger percentage of the market capitalization-weighted

S&P 500 Index than their unweighted number, indicating

that these tend to have higher market capitalizations

than stocks in the other buckets.

Management teams at these companies are taking

advantage of the low-cost debt available in the market,

and their ability to pay down their debt with cash at

hand means these tend to be low-leverage-risk investment

opportunities. This does not necessarily mean

such low-leverage-risk stocks are good investments,

because there is also valuation risk. An investor would

have to analyze many more aspects of the stock and

the company before making that decision.

Among Maryland-based companies, T Rowe Price

(ticker: TROW) is in the least-levered group on both

net debt/equity and net debt/EBITDA metrics.

On the other end of the spectrum, 10% to 17% of S&P

500 stocks have net debt representing multiples of their

shareholders’ equity and/or trailing-12-month EBITDA.

These stocks represent 20% of the index in terms of

the number of companies, but a smaller percentage

in terms of index weight, which indicates a smallermarket-

capitalization bias in this group. Consumer

discretionary and utilities represent the largest share

of highly levered companies on both leverage metrics,

and numerous industrials and real-estate companies

are also highly levered, based on net debt/equity and

net debt/EBITDA, respectively.

Among Maryland-based companies, Apartment Investment

& Mortgage (ticker: AIV), Extra Space Storage

(ticker: EXR), Federal Realty Investment Trust (ticker:

FRT) and UDR (ticker: UDR) are four local REITs (realestate

investment trusts) in the most-levered category,

based on both leverage metrics.

Being Highly Levered Is Sometimes OK

Being among the most-levered stocks does not necessarily

mean these stocks should be avoided in a portfolio.

A large debt load is part of the business model for many

businesses, such as utilities and real-estate companies.

For this reason, it is up to each investor to analyze stocks

with high leverage ratios to determine whether the leverage

is appropriate for the business model and to assess

its impact on the investment’s overall attractiveness. In

fact, detailed analysis of a levered company that has

the business fundamentals to manage the debt through

difficult times might create an opportunity to invest

at an attractive entry point, if the stock trades down

with other levered stocks in a distressed environment.

Additionally, simple leverage ratios such as those in

this analysis do not constitute a complete analysis of

a stock’s leverage risk or its merits as an investment

opportunity. However, many passive and algorithmic

investment vehicles rely on simple ratios to divide an

investment universe into attractive and unattractive

buckets, and to create long-short portfolios2 to capture

the performance differential of stocks in each bucket.

This is a simplistic description, but the key point is that

the widespread popularity of passive investment vehicles

makes it common to find sharp stock price movements

because the stock is part of a thematic bucket, rather

than because of its fundamentals. In this way, these

metrics’ simplicity can be a powerful causal factor in

framing securities and driving their prices.

Conclusion: Higher Risk of Debt Crisis

and More Need for Leverage Analysis

Rising levels of debt at the federal and corporate levels

are increasing the risk of corporate bankruptcies and

a debt crisis as interest rates eventually return to more

normalized levels. This risk may not be at the forefront

of investors’ attention due to historic levels of fiscal and

monetary stimulus around the globe, but the pressure

is building under an otherwise calm surface of increasing

indebtedness. For investors, it is inappropriate to

generalize the effects of high leverage on individual

companies because so much depends on an individual

industry’s or company’s business model. Detailed leverage

analysis should be in every investor’s stock analysis

toolkit. This would help avoid the risk of distress in

highly levered companies and protect clients’ capital

in case of a debt crisis. At the same time, such analysis

could create investment opportunities if highly levered

companies become undervalued and less-levered companies

become overvalued as quantitative strategies use

leverage as a crude measure of attractiveness.

References

Mustafa, Farhan (2020). “Former FDIC Chair Sheila Bair Is

Optimistic About the Potential of Technology to Improve Financial

System, While Expressing Concern About Non-Financial Debt

Segment of the Market,” Baltimore Business Review.

O’Malley, Niall (2020). “When Does A Good Investment Become

a Bad Investment?” Baltimore Business Review.