Nicola Daniel, Executive Director, CFA Society Baltimore

Fintech — or financial technology — is the latest disruptive innovation taking aim at the huge institutions that deliver financial services to individuals and businesses today. According to consulting firm KPMG, close to $13 billion was invested in U.S.-based fintech companies in 2016. Globally, venture capital-backed fintech companies raised $5.2 billion in the second quarter of 2017, a number that will surpass last year’s global record if sustained through the end of the year.

“Unicorns” — companies, usually start-ups, without an established performance record valued at more than $1 billion — are considered the Holy Grail of the venture capital investing space. Globally, the fintech space claims 26 unicorns valued at $83.8 billion. North America leads with 15 fintech unicorns, followed by Asia with seven, and Europe with four.

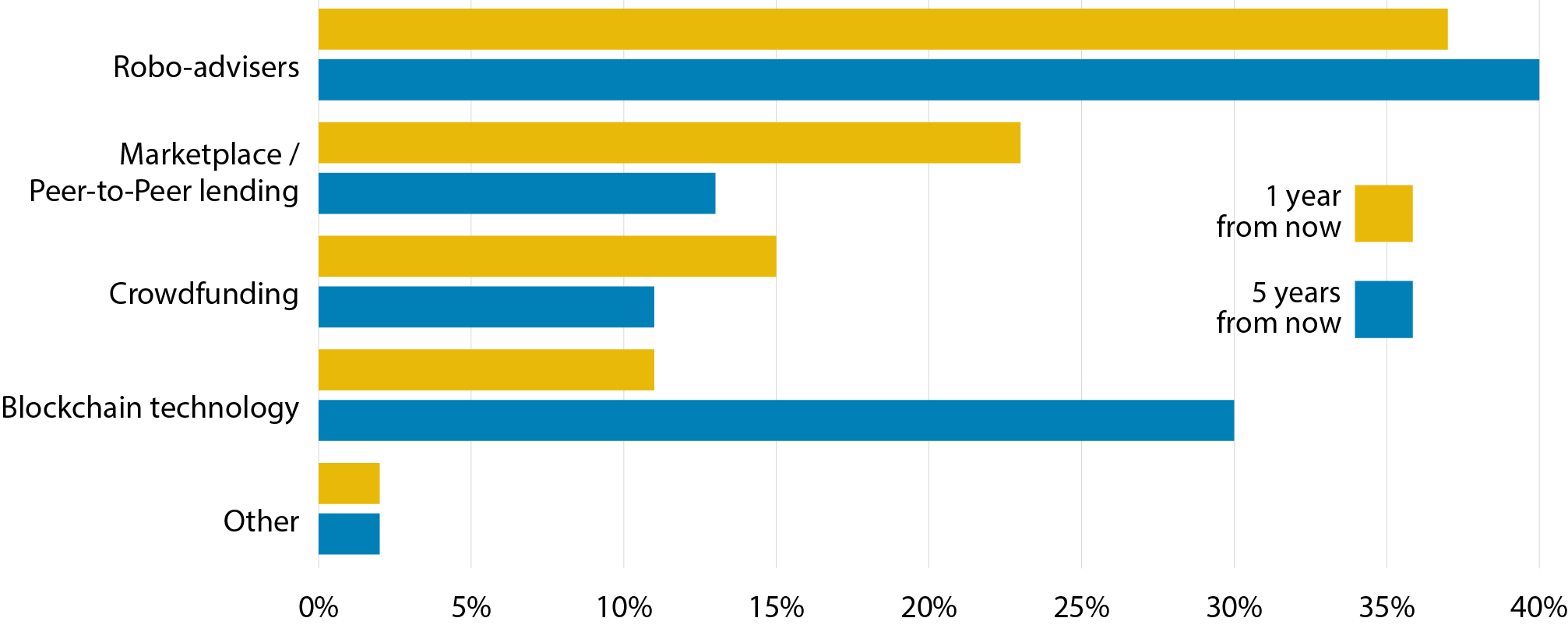

Start-up companies have broken new ground in a number of specialties within the financial services industry, including digital investment management, digital lending, mobile pay- ments, and digital ledger (blockchain) technology, among others. A March 2016 CFA Institute Fintech Survey of more than 3800 institute members demonstrates industry partici- pants’ expected impact of fintech innovation on the financial services industry by timeline. (See Figure 1)

In the interest of brevity, we limit our discussion to three areas of fintech: digital investment management, digital lending, and mobile payments. We leave digital ledger (blockchain) out of this discussion because of its inherent depth and complexity with one cursory observation. The recent massive Equifax data breach, which affected 140 million individuals in the US, is certain to hasten the adoption of more secure methods of storing data. Blockchain may well be a major beneficiary. Regulators and law enforcement embrace block- chain technology for its ability to make financial transactions fully traceable to the source, aiding anti-terrorism efforts and potentially rendering money laundering through the banking system a thing of the past. For further information about blockchain technology, please refer to the resource references at the end of this article.

Digital Investment Management

Digital investment management is often referred to as robo-advising. While there is no standard definition, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) defines robo-advisors as digital investment advice tools that“support one or more of the following core activities in managing an investor’s portfolio: customer profiling, asset allocation, portfolio selection, trade execution, portfolio rebalancing, tax-loss harvesting, and portfolio analysis.”

Figure 1: Greatest Impact on Financial Services Industry, by Timeline

Two of the most prominent start-up robo-advisors are Wealthfront and Betterment. Both were founded in 2008 and are considered the earliest movers in the digital investment advice space. In addition, virtually all major brokers have launched some sort of automated brokerage advice platform to individuals, including Vanguard’s “Personal Advisor Services” and Charles Schwab’s “Intelligent Port- folios.” Even some of the major pension fund managers like TIAA-CREF extend automated advice as part of their suite of employer-sponsored retirement account offerings. Finally, other behemoths have acquired robo-advising technology, such as Blackrock’s acquisition of FutureAdvisor.

These digital investment management platforms offer financial advice at a considerably reduced cost compared to a traditional investment advisor. Both Wealthfront and Betterment, for example, charge a fee of 0.25% for portfolios larger than $10,000. Betterment goes one step further to offer the first year of service free with a $10,000 deposit, while Wealthfront gives free service to any account smaller than $10,000. Both allow investors to open accounts with minimal to no deposit. Meanwhile, larger platforms such as Schwab charge slightly higher fees of 0.28% with a $25,000 minimum.

These fintech platforms mainly invest in low-cost passive investment vehicles like exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Portfolio construction is limited to asset class allocation, rather than individual security or instrument selection. Additionally, most robo-advisors offer automated portfolio rebalancing and tax-loss harvesting strategies, so clients do not have to implement these investment services themselves, or pay excessive fees to individual financial advisors (FAs) for such services.

Table 1: Asset Allocation Model Comparison

| Asset Class | Digital Adviser A | Digital Adviser B | Digital Adviser C | Digital Adviser A | Digital Adviser D | Digital Adviser E | Digital Adviser F |

| Equity | 90.1% | 72.0% | 51.0% | 84.0% | 60.0% | 69.0% | 72.2% |

| Domestic | 42.1% | 37.0% | 26.0% | 34.0% | 30.0% | 47.0% | 28.9% |

| U.S. total stocks | 16.2% | 22.0% | 34.0% | 47.0% | 13.0% | ||

| U.S. large-cap | 16.2% | 8.0% | 19.0% | 13.0% | |||

| U.S. mid-cap | 5.2% | ||||||

| U.S. small-cap | 4.5% | 18.0% | 11.0% | 2.9% | |||

| Dividend stocks | 15.0% | ||||||

| Foreign | 48.0% | 35.0% | 25.0% | 50.0% | 30.0% | 22.0% | 43.3% |

| Emerging markets | 10.5% | 16.0% | 13.0% | 25.0% | 9.0% | 9.0% | 17.0% |

| Developed markets | 37.5% | 19.0% | 12.0% | 25.0% | 21.0% | 13.0% | 26.3% |

| Fixed income | 10.1% | 13.0% | 40.0% | 10.0% | 21.5% | 11.0% | 15.0% |

| Developed markets bonds | 15.0% | 2.5% | 4.1% | ||||

| U.S. bonds | 4.9% | 6.0% | 25.0% | 10.0% | 12.0% | 10.9% | |

| International bonds | 3.6% | ||||||

| Emerging markets bonds | 1.6% | 7.0% | 7.0% | ||||

| Other | 0.0% | 15.0% | 9.0% | 6.0% | 10.0% | 16.0% | 12.8% |

| Real estate | 15.0% | 9.0% | 6.0% | 5.0% | 12.8% | ||

| Currencies | 2.0% | ||||||

| Gold & precious metals | 5.0% | ||||||

| Commodities | 14.0% | ||||||

| Cash | 8.5% | 4.0% |

Asset Allocation Models for a 27-Year-Old Investing for Retirement, September 2015 Source: Cerulli Associates. Note: Columns may not total to 100% due to rounding.

Robo-advisors also help to minimize conflicts of interest between clients and individual FAs. These conflicts of inter- est formed the basis of the Department of Labor Fiduciary Rule changes proposed last year. Briefly, the current law requires FAs to select “suitable” investments for their clients and the DOL proposed changing this to a stricter “fiduciary” standard that would require FAs to consider their clients’ interests ahead of their own.5 Therefore, computer-driven robo-advisors are designed to protect unsuspecting clients from such conflicts of interest.

However, conflicts of interest may still arise at the level of the firm vis-à-vis the client. For example, algorithms may favor allocation of assets toward funds in which the digital advisor has a financial interest. Some financial services firms seek to avoid potential conflicts of interest by not offering proprietary oraffiliated funds, or funds thatprovide revenue-sharing payments. Other firms offer affiliated funds, but disclose the relationship to the client.

In addition to lower costs, proponents of robo-advisors argue that their algorithm-driven investment advice is objectively measurable. Retail investors obtain investment advice by answering a series of questions about their financial profile and their risk tolerance. These inputs are fed into an algorithm, which generates asset allocation and portfolio selection recommendations. Indeed, the use of algorithms reduces investors’ emotional temptation to, for instance, “buy high and sell low” that often comes in circumstances of uncertainty and extreme market volatility.

Algorithms can also perform standard portfolio rebalancing tasks more efficiently and accurately than humans can. On the margin, this activity can contribute to outperformance relative to the average investor.

Nevertheless, the questionnaires that feed the algorithms are ultimately human constructs, as are the answers provided by the end-user. Data inputs and assumptions can yield vastly different investment recommendations. In the CFA Institute Fintech survey of members cited earlier, 46% identified flaws in advice algorithms as one of the biggest risks to consumers. The members’ concerns are borne out by empirical evidence. FINRA’s digital investment report cites a study of seven different automated investment platforms. In the study, information about the same theoretical 27-year-old saving for retirement was inputted into each platform. The seven platforms each yielded radically different investment recommendations for the same individual. For example, the equity asset allocation for the identical 27-year-old individual ranged from a low of 51% to a high of 90%. Obviously, the long-term investment outcomes for such variant portfolio allocations would be diverge markedly.

Thus, as with all products in the financial services, consum- ers are wise to exercise caution in selecting providers and to become informed of the underlying assumptions that drive the outputs of automated advice.

Without a doubt, democratized access to investment advice for younger and lower-income individuals with smaller savings pools is good for both savers and providers of financial services. Anecdotally, brokers say that individuals are willing to use automated investment advice up until they have accumulated $100,000 in savings. After that, investors will seek financial counsel that is augmented by an experienced professional. Intuitively, such a threshold makes sense given that wealth management increases in complexity as the portfolio size grows. Issues such as more nuanced tax management; allocation towards different types of savings, including both college 529 and retirement accounts, and estate planning become increasingly more relevant as an investor’s portfolio grows and their circumstances evolve.

Digital Lending

A second major fintech innovation has been through digital lending. Digital lending is primarily lending that takes place outside of the traditional banking system through Web-based ormobile phoneplatforms. S&P’s Global Market Intelligence estimates that the 13 largest digital lenders originated approximately $28 billion in loans in 2016. That is a tiny slice of the total $3.7 trillion in consumer debt held by Americans in August 2017.6

As with digital wealth management, digital lending offers the beneficial feature of convenience and broadens access tootherwise under-served communities. While Congress in the past has sought to mandate some modicum of lending to underbanked communities, barriers to entry such as geographical location and prohibitive cost of acquiring customers have proven intractable. The arrival of digital lending hasmarkedatransformational change in themarket structure of lending to individuals and small businesses by reducing the cost of acquisition, and thus has naturally started to fill in the lending gap in underbanked regions.

Quick access to liquidity has proven particularly valuable to small businesses in need of working capital. Whereas banks often take weeks to transfers funds to users, digital lenders can often fund accounts within the same day.

Figure 2: Major Bank Investments to VC-Backed Fintech Companies Q4 ‘15 – Q4 ‘16

Source: CB Insights

This makes digital lenders especially attractive partners for small businesses seeking to manage payroll and inventory cash flow requirements.

Digital lenders differ from traditional banks not just in their rapid delivery mechanisms, but in their credit scoring systems. They do notrely exclusively on credit scores supplied by the major credit agencies, which means they can target groups that often lack sufficient credit history for them to qualify for loans through conventional avenues.

In the place of standard credit scores, digital lenders have developed their own sophisticated scoring methods based on “alternative data.” Much of this involves the use of big data and artificial intelligence. Indeed, at a recent fintech conference at Yale University, Goldman Sachs partner Paolo Zannoni posited that with the huge amounts of public information available about individuals, it is entirely feasible to establish credit profiles based solely on data available in the public domain.7

Behemoth banking incumbents like JP Morgan and HSBC are increasingly looking to fintechs not as competitors but as partners to help improve operations and reach new con- sumers. Indeed, significant regulatory barriers may require some fintechs to join forces with larger entities in order to prevail in the tough competitive environment. Investments by major banks in fintechs have been steady over the past several years. Figure 3 from CB Insights Global Fintech Report 2016 shows the numbers of investments by major banks over the five quarters through December 2016.

Digital Lending & Regulatory Frameworks

Digital lending is a new service and there is still no clear regulatory framework to manage service providers’ activi- ties. Marketplace lenders are a subgroup of digital lenders that essentially act as brokers. They generate revenue from origination and servicing fees. Such marketplace lenders sell loans immediately to banks and investors, and therefore do not retain credit risk on their balance sheets.

Direct lenders, on the other hand, behave more like banks, although they are not subject to the same bank supervision by regulators, nor do they have the same state-level licensing. Like banks, they hold loans to maturity and earn a profit on the spread between their borrowing cost and their lending income. They rely on lines of credit at commercial banks or their own balance sheet for capital. Indeed, many lenders rely on regulated banks to issue loans on their behalf.

Digital lenders face considerable challenges fromstateregula- tors and industry groups who question their methods and practices. Many digital lenders have actively been calling for more regulatory oversight of their business, so that the boundaries in which they can do business are clear. Data privacy and security, compliance, and fair lending violations are but a few of the issues around which digital lenders seek guidance.

Until now, non-bank lending has been primarily regulated at the state level. However, given the inherently interstate nature of online lending, federal preemption of state regu- lations may be justified to provide a consistent regulatory environment. Moreover, the rapid pace of innovation and complexity of the technology almost certainly prevents regulators from creating adequate rules-based regulations to keep up with the speed of change. This may imply a move away from rules-based governance toward a more controversial principles-based regulatory structure. At times, rules created tobenefit consumers can in fact generate negative externalities if they prevent innovation by startups who may lack the resources to meet significant compliance burdens. The move away from rules-based to principles- based regulation may alleviate the downside of negative unintended consequences brought on by such a structure.

Whatever the case, as the fintech space continues to grow, the role and need for a sound regulatory environment will continue to be of paramount important to the overall health of the U.S. banking system. Most observers of fintech agree that regulators in Asia and Europe are ahead of the U.S. in understanding the nuanced interface of technology and financial services. Regulators in the U.K. have been particu- larly successful in regulating in such a way that encourages innovation. The good news is that U.S. regulators do not have to reinvent the wheel, as they have the U.K. and other models to learn from and adapt to our own markets.

Mobile Payments

As it is in the regulatory regime of digital lending, the U.S. is also behind the rest of the world in the usage of mobile payments. Mobile payment services accelerate the pace of payments relative to traditional services and allow trans- actions to take place a negligible cost. Such payments are also referred to as mobile money, mobile money transfer or mobile wallet, and are used as an alternative to cash, check or credit card payments.

Not surprisingly, mobile payments have been especially suc- cessful in markets where previously underbanked consumers have been able to take advantage of new mobile infrastruc- tures to improve their financial standing. The world’s most popular integrated mobile application is WeChat. WeChat originates from China, and originally began as an instant messaging platform similar to WhatsApp. Within a matter of a few years, WeChat is the app on which consumers can place phone calls, send money, shop, order food for delivery, pay bills, and many other transactions.

In the U.S., the largest number of users of mobile payments are not surprisingly in the under-35 demographic, the Millennials. PayPal is the most popular mobile payment platform in the U.S., and it is currently accepted by 35% of U.S. retailers. PayPal’s annual mobile payment volume was $102 billion in 2016.

Older demographics largely prefer credit cards and other methods of payments, citing concerns over security and complexity of using the apps. Ironically, mobile wallets are especially helpful in curtailing credit card fraud through card-skimming. Nevertheless, security concerns are not entirely unwarranted.

Peer-to-peer payment apps have weaknesses unique to their format. For example, fraud or identity theft on peer-to-peer payment apps can lead to irrevocable spending in client accounts, as these are not protected by fraud insurance. Despite their convenient interface, peer-to-peer payments still rely on the traditional banking infrastructure that ungirds the ATM system. In addition to security concerns, merchants still pay processing fees for retail purchases, which they absorb. So, in this sense there are no cost advantages created.

Table 2: Maryland/DC-area Fintech Start-Ups

| Firm Name | Service/Specialization | City | Total VC Funding |

| Blispay Inc. | Consumer Credit | Baltimore | $25M |

| eOriginal, Inc. | Financial Document Management | Baltimore | $35M |

| EverSafe | Identity Theft & Account Monitoring | Columbia | $250k |

| iControl Systems USA, LLC | Payment Management | Bethesda | $20M |

| FS Card Inc. | Consumer Credit | Washington D.C. | $30M |

| MPower Financing | Student Loans | Washington D.C. | $10.5M |

| Fundrise | Private Real Estate Investing | Washington D.C. | $55.5M |

| Source: Crunchbase10 |

Maryland’s Entrepreneurs

Maryland’s Fintech Entrepreneurs operate across a variety of spaces. Table 2 shows some of the largest start-ups that have recently received VC funding.

Conclusions

The fintech space is vast and ever-growing. This brief overview has considered some of the major innovations in fintech that have had a significant effect on how consumers operate at a global scale. Other aspects of innovation not considered in this article are those technologies that target business efficiencies. Blockchain is one mentioned earlier. Another is how artificial intelligence may be used to aid financial analysts and portfolio managers to deliver investment management services more effectively and at a lower cost in ways that may ultimately offer far more value than robo-advising. In closing, we share data on Maryland’s entrepreneurs in the fintech space.

Blockchain Technology Readings

- Diedrich, Henning. Ethereum: Blockchains, Digital Assets, Smart Contracts, Decentralized Autonomous Wildfire Publishing, 2016.

- FINRA, “Report on Distributed Ledger Technology,” January Available at http://www.finra.org/sites/default/files/FINRA_Block- chain_Report.pdf

- Marvin, “Blockchain: The Invisible Technology that is Changing the World,” PC Magazine, August 29, 2017. https://www.pcmag.com/ article/351486/blockchain-the-invisible-technology-thats-changing- the-world

- Tapscott, Don, “How the blockchain is changing money and business,” TED Talk, June, 2016

- Tapscott, Don, Blockchain Revolution (New York: Penguin Books, 2016).

- US Government, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board, Washington, C., September, 2016. “Distributed Ledger technology in payments, clearing, and settlements.” Available at https://www.federalre- serve.gov/econresdata/feds/2016/files/2016095pap.pdf

References

- CB Insights Research, “The Global Fintech Report, Q2 ’17,” https://www. cbinsights.com/research/report/fintech-trends-q2-2017 (accessed Sept. 12, 2017)

- CFA Institute, “Fintech Survey Report,” April 2016, https://www.cfain- stitute.org/Survey/fintech_survey.PDF (accessed Sept. 15, 2017

- FINRA, “Report on Digital Investment Advice,” March 2016. Available at http://www.finra.org/sites/default/files/digital-investment-advice- report.pdf

- BlackRock press release, “BlackRock to Acquire FutureAdvisor”; August 26, 2015. Available at https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/en-pl/litera- ture/press-release/future-advisor-press-release.pdf

- See “The DOL Fiduciary Rule: What Is It and Why Should We Care?” in the 2017 Baltimore Business Review: https://www.cfasociety.org/ baltimore/Documents/BBR_2017%20copy.pdfU.S.

- Government, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Consumer Credit Outstanding, https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/ g19/HIST/cc_hist_sa_levels.html (accessed Oct. 14, 2017)

- Paolo Zannoni, “Novel payment, investment and transfer mechanisms challenging states & institutions,” Yale School of Management Fintech Transformation Conference, October 13, 2017.

- CB Insights Research, “The Global Fintech Report: 2016 in Review,” pg. 25, https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/fintech-trends-2016 (accessed Sept. 12, 2017)

- Statista, https://www.statista.com/topics/982/mobile-payments (accessed Oct. 18, 2017)

- Crunchbase, https://www.crunchbase.com (accessed Oct. 14, 2017)