Michaël Dewally

Associate Professor, Department of Finance, Towson University

Yingying Shao

Associate Professor, Department of Finance, Towson University

On March 22, 2018, “President Trump put China

squarely in his cross hairs” according to The New York

Times. The White House had just announced tariffs on

$60 billion worth of Chinese goods. The announcement

was part of continued economic tension between the

two nations. The current White House administration

had shifted its stance on economic relations with

China. Rather than encourage trade with China and

rely on China’s efforts to participate in rules-based

agreements, the administration sees its trading partner

as an economic adversary. The decision is a reaction to

questions of fairness of trade with its partner, the U.S.

accusing China of trying to obtain American technology

and trade secrets.

The timing, magnitude and coverage of the tariffs were

unprecedented. This action came at a time when production

sharing across the two countries is at an all-time

high. The market reaction to this escalating trade war

was immediate. We document the varied reactions as

we report the stock price movements for all firms in the

U.S., firms in the Maryland-Delaware-Pennsylvania-

Virginia region and across industries.

The administration had two weeks to reveal the list

of targeted products. The market reaction on these

early days was knee-jerk as the White House had not

sketched out full details of the products that would be

subject to the 25% tariff. The market reacted strongly

negatively. The tension had been building with trade

partners but the White House actions had not targeted

a single trade partner as much up to this point. The

steel and aluminium tariffs announced earlier in March

2018 hit China to a much smaller extent, most of those

tariffs impacting Canada. This new announcement

had the potential to hurt companies for two reasons.

First, firms with suppliers in China would see their

input costs increase as tariffs would raise the prices

of Chinese goods, and would increase the demand for

and the prices of alternate suppliers’ goods. This would

guarantee profit margin pressures for these companies,

if not outright disruption. Second, firms that sell to

China would likely suffer as China was to inevitably

retaliate. The Chinese reaction was in fact immediate

with its own tariffs announcement the following day.

Following the steps of Huang et al. (2020), we focus

our study on the market reaction over the three trading

days surrounding the announcement. We report not

only the 3-day cumulative raw returns (CRR) but also

the market-adjusted cumulative abnormal returns over

the same 3-day window (CAR).

How do stocks of firms in the Maryland-Delaware-Pennsylvania-Virginia region react?

Using data from The Center for Research in Security

Prices, we collect information on all actively traded

firms that are headquartered in Maryland, and the three

states surrounding Maryland. We retrieve information

on 199 firms and proceed to compute the CRRs and

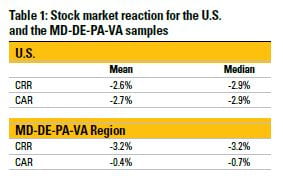

CARs for our sample. We report the results in Table 1.

Table 1 provides summary statistics for CRR and CAR for

the entire U.S. sample of listed firms, excluding financial

firms, as reported in Huang et al. (2020), and the statistics

for the regional sample we created. Overall, the market

reaction to the announcement pushed returns down a

nearly full 3%. The CARs match that number as well.

The distribution is fairly symmetric as Mean and Median

are close to each other. For our regional sample, the raw

reaction is similar to that of the entire nation, showing

a swift negative reaction to the announcement. The

CARs evidence though shows a more muted regional

reaction than nationwide. This evidence requires further

investigation. On the one hand, it hints at a lower reliance

on China for imports and exports. On the other

hand, it highlights smaller headways in trade with the

U.S. largest single-country trading partner. Regardless

of the outlook on the situation, the region’s response

to the announcement was muted.

Observations from the disruption of supply chain from

and potential impairment of sales to China suggest

that firms involved in Manufacturing sectors would

suffer a stronger response to the trade war announcement

than firms in Non-Manufacturing sectors. We

next investigate the causes of the market reaction in

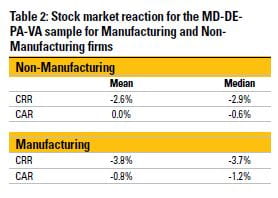

relation to industry distributions. Table 2 splits the

regional sample into two sub-samples. It is clear from

this table that Manufacturing firms suffer the most

from the announcement. Manufacturing firms in the

region experienced an average loss of 3.8% whereas

Non-Manufacturing firms lost only 2.6%. In abnormal

returns term, the Non-Manufacturing sector showed no

reaction (0.0% on average) while the Manufacturing

sector lost 0.8%.

How do stocks of firms in Maryland react?

Were Maryland firms affected differently than their

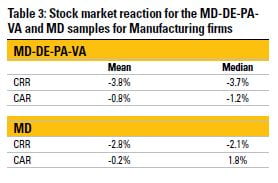

counterparts in the region? Table 3 reports similar

statistics to the previous tables. In Table 3, we focus

entirely on Manufacturing firms, those firms most affected.

We separate the Maryland group from those

for the entire region. Maryland Manufacturing firms

in general experienced a smaller stock market decline

than firms in the region. The average CAR for Maryland

firms was only -0.2% compared to -0.8% for the region.

Variations nationwide and within the region are certainly

attributable to the distribution of sector activities in

each state. In order to control for these variations in

aggregate, we use Huang et al. (2020)’s methodology

and introduce an industry level measure of Chinese

Import Penetration (IP). Defined as the ratio of Chinese

Imports in the industry to the sum of the industry’s

Shipment Value plus Imports minus its Exports, the

IP measure captures the industry’s “direct trade exposure”

by measuring “the perceived reduction in import

competition from and exports to China.” Huang et

al. (2020) find a positive relationship between IP and

CAR: firms in an industry where Chinese imports are

prevalent will benefit from the enactment of tariffs as

the reduced competition from Chinese products will

boost domestic companies’ profits.

We compute the IP for firms in our sample at the 3-digit

SIC level1. For example, SIC Code 211 for the Cigarettes

industry has a low IP of -0.19 as the industry faces little

competition from Chinese imports. Meanwhile, the IP

of SIC Code 282 for Plastic Materials is a high 0.43

as the industry faces severe competition from Chinese

imports. On balance, given the values in Table 3, we

would expect the aggregate IP of Maryland firms to be

higher than the region’s aggregate IP as the MD CARs

are higher than the region’s. Our computation shows

an IP for the MD firms of 0.09 while the IP for firms in

the other 3 states is 0.12. A further look at the distribution

of Manufacturing in Maryland versus the region

shows that only 3 out of 17 (18%) MD firms have an

IP over 0.1, while, in the rest of the region, 34% (13

out of 38) have an IP in excess of 0.1. That is, firms in

the region are in industries that face more competitive

pressures from Chinese imports. These findings are the

opposite of those from the general regression results

in Huang et al. (2020). This shows that using industry

aggregated levels of exposure to Chinese competition,

while helpful on a large scale, can hide variations within

the industry itself.

Given the limitations of the IP measure exposed above,

we turn to individual stock’s reactions on the day of

the announcement. In particular, we focus on those

firms’ recorded exposure to the Chinese markets. In

Maryland, we contrast the market reactions of U.S.

Silica and W.R. Grace. On the one hand, U.S. Silica had

a +2.2% raw return over the 3-day period. U.S. Silica

does not report any international sales nor international

suppliers in its most recent annual report. The nature

of U.S. Silica’s business leaves the company insulated

from any direct impact from the trade war. On the other

hand, W.R. Grace’s stock price dropped 6.2% over the

same time period. W.R. Grace’s exposure to China is

manyfold. W.R. Grace maintains both production and

credit facilities in China. W.R. Grace’s revenues from

Asia-Pacific represents nearly 25% of its $1.93 billions

in sales for 2018. As such, W.R. Grace was primed to

suffer from the trade war. Universal Security Instruments

is similarly exposed to Chinese imports as it has a joint

venture in Hong Kong supplying it with components.

Universal Security Instruments’s stock price dropped

3.2% on announcement. In the region, United States

Steel in PA experienced the steepest drop of 12%. The

surprise announcement of the new tariffs reiterated the

administration’s resolve in its new trade policies and

dealt a new blow to the steel manufacturer.

More than the direct adverse impact to companies’ stock

prices, the trade war imposed a concern for the State of

Maryland. According to Trade Partnership Worldwide’s

white paper on the projected impact on the U.S. economy

of the trade war, over 800,000 jobs in Maryland are

supported by trade. Of these, 18,800 are threatened

by the trade war. The enacted tariffs impacted 3% of

the Port of Baltimore’s annual tonnage. In December

2018, a survey by the Maryland Chamber of Commerce

revealed that 54% of its members reported that current

trade policies negatively affected their businesses. While

the COVID-19 pandemic has slowed down trade talks

with China, unresolved issues around trade remain a

threat to Maryland businesses.

Reference

1Data source: https://sompks4.github.io/sub_data.html

Landler, Mark and Tankersley, Jim, Trump Hits China with Stiff

Trade Measures (March 22, 2018), The New York Times.

Huang, Yi and Lin, Chen and Liu, Sibo and Tang, Heiwai, Trade

Networks and Firm Value: Evidence from the US-China Trade

War (April 30, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/

abstract=3227972 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3227972

Maryland Chamber of Commerce – https://mdchamber.org/maryland-

chamber-talks-tariffs/

Trade Partnership Worldwide, LLC, Estimated Impacts of Tariffs

on the U.S. Economy and Workers (February 2019), https://

tradepartnership.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/All-Tariffs-

Study-FINAL.pdf