Finn Christensen

Associate Professor, Department Of Economics, Towson University

The live music industry had been booming prior to the coronavirus pandemic. According to estimates from Pollstar, an industry magazine which gathers concert box office data, ticket revenue from live performance in North America climbed from $2.47 billion in 2000 to $8.18 billion in 2017. Recently, however, the coronavirus pandemic has taken a heavy toll. Despite a few months of normal activity prior to the lockdowns, the 2020 mid-year gross was only 54.4 percent of 2019’s mid-year gross. Locally, the stages of Maryland venues have fallen silent since mid-March 2020, and some smaller local venues have shut down permanently. Although the industry has been severely impacted, recent research by me and others suggests that increasing streaming trends will continue to stimulate the demand for live music post-pandemic.

Trends in Live Music

Before discussing the role of streaming, let’s first unpack the pre-pandemic industry revenue trend into its constituent parts: ticket prices and tickets sold.

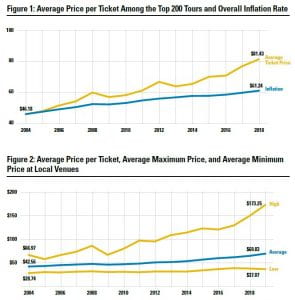

One way to do this is to concentrate on the top tours since data are available from Pollstar’s annual list of the top 200 grossing tours in North America. The average ticket price in 2004 among this elite group was $46.18. If prices had simply kept up with inflation, then the average ticket price in 2018 would have been $61.24. In reality it was $81.43.

Despite this rapid increase in prices, the number of tickets sold among the top 200 tours increased from 46.1 million in 2004 to 55.5 million in 2018. The fact that both ticket prices and tickets sold increased indicates that the demand for live concerts increased over this time period.

National price and sales data for tours outside the top 200 are difficult to obtain, but I do have data on some local venues where concerts are performed. Dedicated venues host events from a wide variety of artists, not just the elite ones who make the top 200. If we observe similar trends at the venue level then we can be more confident that the changes in the live music are industry-wide rather than concentrated at the top.

Data quality for any specific venue varies, so I aggregate data across six Baltimore-Washington area venues. These include the Capital One Arena in downtown DC, the EagleBank Arena in Fairfax, VA, the Filene Center in Wolf Trap, VA, the Royal Farms Arena in downtown Baltimore, the Merriweather Post Pavilion in Columbia, and the MECU Pavilion (formerly Pier Six) at Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

The average ticket price across all six venues increased steadily from $42.56 in 2004 to $69.83 in 2019, far above the price of $56.44 that inflation alone would have predicted. Part of what is driving this price increase is an industry trend toward greater price discrimination. The best seats are increasingly sold at a premium. In fact, while the lowest priced tickets have merely kept pace with overall inflation, the highest priced tickets have nearly tripled since 2004.

Ticket revenues go to artists and promoters while venues make money through rental fees, sponsorships, concessions, and parking. In this sense venues care very much about the number of shows and attendance. Across all six Baltimore-Washington venues, annual ticket sales increased from around 1.1 million in 2000 to 1.8 million in 2019. This increase came about through a combination of selling a higher percent of a show’s capacity and an increase in the number of shows per year. In Figure 3 I use a three-year moving average for number of shows to smooth out year-to-year fluctuations.

All told, the numbers from the top 200 tours and local venues are broadly consistent. Demand for live concerts has been increasing industry-wide since the digitization of music.

Digitization and Live Music

While live music revenues were growing, the recorded music industry was transitioning from distributing music on CDs to distributing it though the Internet. In the early days of digital music, illegal file-sharing, or piracy, using software such as Napster was prevalent. In the mid to late 2000s, paid downloads and ad-based streaming through services like YouTube and Pandora became popular. In the 2010s, freemium streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music which now dominate the space began to emerge in the United States.

Digitization could stimulate the demand for live music in several ways. Compared to traditional radio and purchasing CDs, streaming provides the consumer a more interactive experience and access to more music. Users can discover and explore music more easily, making it easier to form the emotional connection to an artist’s music that drives concert attendance. Also, concerts are more fun if you know the songs and can sing along. Streaming has lowered the cost of this concert preparation. Finally, listening to a recording is enhanced if one can reminisce about going to a concert, and knowing this in advance can make attending a concert more attractive. The on-demand nature of streaming services makes this nostalgic listening easier.

Academic research supports the link between digitization and live music. A 2012 study by a team of researchers at Boston College, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the University of Chicago demonstrated that a positive break in trend for live music revenue occurred in 1999, the same year as the Napster launch. Moreover, the break in trend was more pronounced in areas with greater broadband access, consistent with the idea that file-sharing stimulated concert demand.

Evidence from YouTube

In a recent working paper, I demonstrate that the concert business of artists under the Warner label suffered during a blackout of Warner content from YouTube during the first nine months of 2009. This is consistent with the idea that streaming stimulates concert demand.

Warner was one of four major record labels at the time, and all of them were negotiating compensation from YouTube for copyrighted music played in videos on its site. While the other labels were able to strike a deal with YouTube, Warner and YouTube could not. This impasse resulted in the Warner blackout until mutually agreeable terms could be reached.

The Warner-YouTube blackout provides what is known as a “natural experiment.” In this experiment, Warner artists were “treated” with removal from the most popular music streaming site in the world at the time. Non-Warner artists served as the control group. This assignment to treatment and control groups was effectively random as I demonstrate in the paper. Thus, it is plausible that the difference in year-over-year measures of concert business performance between non-Warner and Warner artists can be attributed to the blackout.

Using Pollstar data for the top 200 tours, I show that in the years preceding the 2009 blackout, Warner and non-Warner artists had very similar concert outcomes with respect to revenues, average ticket price, and attendance. But in 2009 Warner artists had a tough year compared to non-Warner artists.

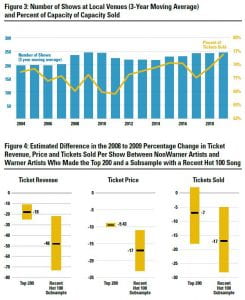

Specifically, I estimate that the percentage change in revenue from 2008 to 2009 was 18 points lower among Warner artists, and the percentage change in average ticket prices was 9.4 points lower. My estimates did not pick up a significant difference in the percentage change in tickets sold per show. These effects are illustrated in the Figure 4. The black square is the point estimate and the yellow band is the 95 percent confidence interval. The fact that the confidence interval around the estimated price effect among the top 200 is barely visible means that the effect was estimated precisely.

It is unlikely that artists were equally affected by the blackout. For example, fans of Willie Nelson or Diana Krall probably did not turn to YouTube in 2008-2009 as much as fans of Taylor Swift or the Spice Girls. The former group of artists were probably less affected by the blackout than the latter. To capture this idea, I estimate the effects of the blackout among a subsample artists who recently had a song in the Billboard Hot 100, a weekly ranking of recorded songs based on sales and traditional radio play (streams were not factored in the ranking in a significant way until 2012.) Thirty-three percent of artists in the top 200 had a recent Hot 100 song.

Among these hot artists, the percentage change in revenue from 2008 to 2009 was 47.6 points lower among Warner artists, the percentage change in average ticket price was 16.8 points lower, and the percentage change in the tickets sold per performance was 16.6 percentage points lower.

The evidence suggests that simultaneous rise in the live music industry and in streaming is more than just coincidence; the rise in streaming appears to have stimulated the demand for live music.

The Impact of the Pandemic

Very few live shows are being played during the pandemic, but venue owners’ fixed costs such as insurance and rent still need to be paid. Small independent and privately-owned venues are particularly vulnerable. In fact, The Soundry in Columbia, MD, the U Street Music Hall in DC, and others have shut down permanently due to the pandemic. Larger players such as AEG and Live Nation Entertainment are more likely to weather the pandemic, so we can expect greater concentration in the venue industry after this is all over.

For industry players who survive, the post-pandemic picture looks rosy. It’s difficult to predict exactly when demand will fully return, but there is a hunger for live music and live events more generally. After all, just think about the 2020 Sturgis motorcycle rally in South Dakota which drew large crowds despite the health risks. And the recent approval and rollout of highly effective vaccines is certainly welcome news.

In addition, paid subscriptions to streaming services have exploded in the last few years as complementary products have emerged such as smart speakers and apps like CarPlay. These products make it easier to use streaming services at home and in the car. While Spotify CEO Daniel Ek acknowledged in a recent earnings call that some of this uptake in streaming is due to podcasts, I suspect that many new subscribers will also be listening to music. If so, we can expect the demand for live music to continue to increase beyond pre-pandemic levels.