Introduction

Modern studies of international relations have grown to emphasize the political importance of language in shaping how individuals think of themselves and their place in the world. [1] The utilization of a particular language implicitly attaches an individual to a particular culture and national identity and the study of language in political geography can offer insights into the primary factors for tension and conflict between nation-states on the international stage. Put simply, language is a powerful tool and must be wielded properly in order to prevent the outbreak of conflict. Thus, it is imperative that the effects of linguistic diversity and cultural fault lines be examined to better understand the current state of geopolitics and prepare for future instances of conflict that emerge as a result of persisting cultural divides.

In the former Soviet Union, language became one of the primary methods of attempting to create a unified socialist society. However, as the power of the Communist Party waned in the late 1980’s, so did the stronghold of the Russian language in Soviet satellite states. Nearly thirty years after the collapse of the U.S.S.R., Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, alongside Russia, remain the only former satellite states to employ Russian as an official language, while the rest of the former Eastern Bloc has reverted to using their pre-Soviet languages for all official purposes.

As a result of Soviet-era linguistic policies, lingering tensions exist between former satellite republics and their ethnic-Russian populations based upon their utilization of the Russian language. Thus, to provide a conceptual framework for implications of language on political geography, this paper will detail a case study on the region of the Former Soviet Union and the ways in which forced linguistic hegemony became a tool of political power for the Communist Party. Furthermore, it will investigate how lingering hostility towards the Russian language can and will continue to contribute to the outbreak of conflict in the region.

Language and Geopolitics

Language is an integral aspect of culture, so much so that linguistics have coined the term, “[l]inguistic determinism,” to refer to the notion that, “the particular language one speaks shapes the way one thinks.”[2] Human attachment to a language indicates that one shares a connection with a unique culture as the acquisition of new words and grammatical structures unveils increasingly complex insights into linguistic thought processes and actions. Languages possess specific colloquial phrases, idioms, and jargon to refer to cultural phenomena, often requiring that one has advanced knowledge of both the language and culture to understand the meaning of the phrase.

Put in the context of geopolitics, language also embodies a sense of patriotism for many. Marshall Singer, professor of International and Intercultural Affairs, writes that, “any language people choose for themselves and their children is a function of their perception of that language’s standing in the world and of the relative importance of the nation or nations that use it.” [3] For example, linguistic similarity imbues a sense of mutual patriotism shared between the Five Eyes, an allied group for intelligence and information-sharing consisting of the most influential, Western English-speaking states: Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and United States.

Linguistic hegemony refers to the process by which a dominant group attempts to eradicate the use of minority languages by coercing others to accept their language as standard and pragmatic. [4] When put into practice, linguistic hegemony can result in the emergence of hostility towards the dominant group, especially if the dominant language is strongly enforced politically. Therefore, in situations where individuals are forced to adopt the new, dominant language, which by proxy, has new cultural and ideological beliefs, they are likely to develop adverse feelings that leave them predisposed to not learn or utilize the dominant language.

Linguistic Transformation in the Soviet Union

Russian was not considered a global language until the inception of the Soviet Union. In fact, nearly two centuries prior, Peter the Great’s Westernization led to an adoption of European cultural practices, including language. By the height of the Russian Empire in the eighteenth century, Russian nobles communicated in French, often with little knowledge of the tongue of ‘Mother Russia’. [5] French was the language of diplomacy and allowed Russia to be perceived by other European states as favorable and westernized. Throughout the nineteenth century, Russian became more widespread and utilized throughout the vast empire. Russification called for the acquisition of a pragmatic language, leading to the development of a standardized Cyrillic alphabet to be taught in schools and used in official publications. By the 1917 Revolution, the Russian language had become the only cultural facet shared by both the autocracy and peasantry.[6]

The Soviet Union began as one of the most ethnically heterogeneous states, possessing over one hundred distinct ethnic groups who spoke approximately 130 languages within the fifteen republics. At its inception, Soviet leadership prided itself on the communist empire’s diverse composition; Lenin rejected Russification and favored broad ethnic diversity as being inherent to the Communist agenda. [7] In fact, Stalin outlines the official Bolshevik linguistic policy in a 1918 article stating, “[e]ach region shall select the language or languages that correspond to the ethnic composition of its population, and there will be complete equality of languages of both minorities and majorities in all social and political institutions.” [8]

By the 1930s, the trajectory of linguistic policy completely shifted to complete Russification of the Soviet Union. The evolution from a diverse ethnic territory to a unified communist state became the focal point of domestic policy, which naturally forced the Russian language to center stage as the primary language of all republics. A 1938 decree made Russian language courses mandatory in all SSR schools in efforts to increase bilingual education and further promote Russification. As a result, non-Russians who were educated with the Russian language as their primary medium of instruction almost always identified Russian at a minimum, as their second language. [9]

Alongside the imposition of mandatory Russian education, influxes in migration dispersed ethnic-Russians throughout the various republics to further Russify other ethnic groups. Stalin’s inter-Soviet passport program encouraged population dispersion and allowed Russians to travel freely to other republics with ease. Between the 1950s and mid 1970s alone, 2.7 million Russian migrants traveled to other Soviet Republics for resettlement and furthering the agenda of the Communist Party. [10] This population diaspora drastically shifted the population distribution across the Eastern Bloc and paved the way for the emergence of future tension between ethnic Russians and non-Russians upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Russian Language Hostility after the Dissolution of the Soviet Union

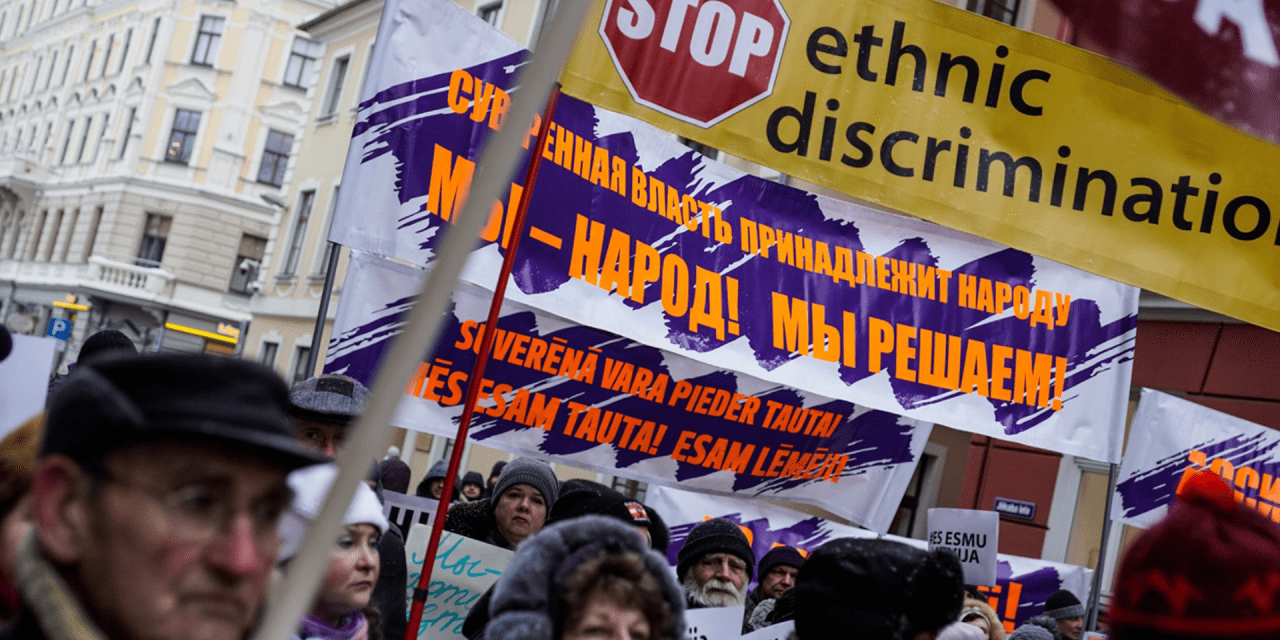

As the Communist Party’s power grew weaker, nationalism grew stronger and more pronounced among non-Russians. Anti-Soviet sentiments called for a rejection of everything Russian, especially in the areas of language and culture. [11] Under Gorbachev’s Perestroika, mass movements erupted calling for ‘linguistic justice’ for the different nationalities of the Soviet Union. [12] Upon the fall of the Iron Curtain, utilization of the Russian language disappeared from the limelight in many former republics. In the Baltics, Russian was eradicated from all school curricula post 1991 and is considered a minority language in the modern era compared to English, which has grown significantly in popularity. In Armenia, the Armenian language was resurrected and restored to its pre-Soviet status as the official language of all educational institutions. [13]

Although the dissolution of the Soviet Union brought an end to the world’s largest multinational empire, the post-1991 era left many ethnic Russians residing in former Republics to live in states with hostile perceptions of the Russian language and culture. In a 2015 survey conducted in Estonia, seventy-seven percent of Estonians disagreed that Russian should be the official language while only seven percent of Russians disagreed. A similar survey found that the majority of ethnic Russians living in Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania heavily favored making Russian the second official language, while the majority of each Baltic state’s ethnic population were in vast disagreement. [14]

In 2014, the annexation of the Crimean peninsula in Ukraine by the Russian government illustrated the length to which linguistic and cultural divides can shape modern geopolitics. Prior to the annexation, Crimea was the only part of Ukraine where Russians were the majority ethnic group, constituting around sixty percent of the population. [15] Similarly, the Russian language was utilized at an even higher frequency among Crimean residents regardless of ethnic identity with around seventy-seven percent percent of individuals stating that Russian was their native language. [16] Regardless of broader implications pertaining to military strategy and national security, the annexation of Crimea was certainly rooted in motivations to reclaim and preserve the territory of ethnic Russians–which has had broad implications for Ukrainian residents. In March 2020, President Putin signed a law effectively barring non-Russians from owning land on the peninsula. [17]

Conclusions and Further Implications

The linguistic and cultural divide in former Soviet Republics poses a potential threat to the current state of the international system. Lack of integration of ethnic-Russians into sectors of employment, education, and government will only contribute to future hostility and the outbreak of potential conflict between ethnic groups. Moreover, who knows how Russia will react if the livelihoods of Russians in the near-abroad are threatened.

Why do these tensions make a difference in the realm of international relations? Fractured ethnic identities within a given state can often lead to political tension and conflict. Simply look at the breakup of other vast empires and multi-ethnic states–the Ottoman Empire, Yugoslavia, Israel/Palestine–ethnic conflicts have had drastic implications both domestically and in regard to the international system. Look to modern Russia and the divide between Chechnya and Tatarstan–the Kremlin has been in direct conflict with disparate ethnic groups domestically who yearn for full autonomy. Who is to say that similar instances may not emerge in other former Republics, as they have with Chechnya and more recently, Ukraine? Of course, only time will tell whether potential threats will evolve into reality; but until then, scholars of international relations must examine lingering tension and be prepared for the emergence of conflict.

Works Cited

[1] Medby, Ingrid A. 2020. “Political geography and language: A reappraisal for a diverse discipline.” Area 52, no. 1 (March): 148-155. DOI: 10.1111/area.12559.

[2] Lewis, Diana M. 2004. “Language, Culture, and the Globalisation of Discourse.” In Intercultural Communication and Discourse. https://www.diplomacy.edu/sites/default/files/IC%20and%20Diplomacy%20%28FINAL%29_Part3.pdf.

[3] Singer, Marshall R. 1998. “Language Follows Power: The Linguistic Free Market in the Old Soviet Bloc.” Foreign Affairs, January/February, 1998. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/1998-01-01/language-follows-power-linguistic-free-market-old-soviet-bloc.

[4] Suarez, Debra. 2002. “The Paradox of Linguistic Hegemony and the Maintenance of Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 23 (6): 512-530. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630208666483.

[5] Lewis, Diana M. 2004. “Language, Culture, and the Globalisation of Discourse.” In Intercultural Communication and Discourse.

[6] “The Russification of National Minorities – Imperial Russia – Government and people – National 5 History Revision.” 2021. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z6rjy9q/revision/7.

[7] Marshall, David F. 1992. “The role of language in the dissolution of the Soviet Union.” Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics 36. https://commons.und.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1318&context=sil-work-papers.

[8] Shelestyuk, Elena. 2019. “National in Form, Socialist in Content: USSR National and Language Policies in the Early Period.” EDP Sciences. https://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/pdf/2019/10/shsconf_cildiah2019_00104.pdf.

[9] Marshall, David F. 1992. “The role of language in the dissolution of the Soviet Union.” Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics 36. https://commons.und.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1318&context=sil-work-papers.

[10] Chudinovskikh, Olga, and Mikhail Denisenko. 2017. “Article: Russia: A Migration System with Soviet Roots | migrationpolicy.org.” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/russia-migration-system-soviet-roots.

[11] Singer, Marshall R. 1998. “Language Follows Power: The Linguistic Free Market in the Old Soviet Bloc.” Foreign Affairs, January/February, 1998. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/1998-01-01/language-follows-power-linguistic-free-market-old-soviet-bloc.

[12] Ehala, Martin. 2017-2018. “After Status Reversal: The Use of Titular Languages and Russian in the Baltic Countries.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 35 (1/4): 473-491. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44983554?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[13] “Armenia: Transformational Peculiarities of the Soviet and Post-Soviet Higher Education System.” 2018. In 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries: Reform and Continuity, edited by Jeroen Huisman, Anna Smolentseva, and Isak Froumin. N.p.: Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_3#citeas.

[14] Ehala, Martin. 2017-2018. “After Status Reversal: The Use of Titular Languages and Russian in the Baltic Countries.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 35 (1/4): 473-491. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44983554?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[15] Pifer, Steven, and Thomas Pepinsky. 2020. “Crimea: Six years after illegal annexation.” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/03/17/crimea-six-years-after-illegal-annexation/.

[16] Said, Hashem. 2014. “Map: Russian language dominant in Crimea.” Al Jazeera. http://america.aljazeera.com/multimedia/2014/3/map-russian-the-dominantlanguageincrimea.html.

[17] Sauer, Pjotr. 2021. “New Crimean Land Law Banning Foreign Ownership Comes Into Force.” The Moscow Times. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/04/01/new-crimean-land-law-banning-foreign-ownership-comes-into-force-a73443.