By: Gel Derossi, Online Creative Nonfiction Editor

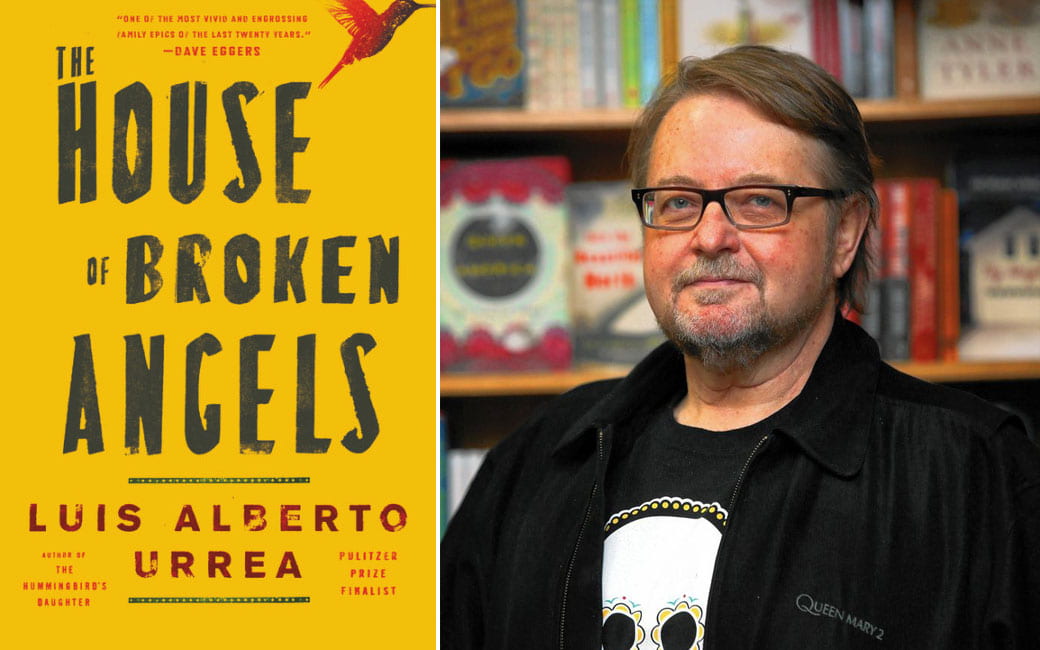

When Luis Alberto Urrea visited Towson University, his vivid presence as a storyteller blurred lines of performance and identity. It is absolutely no wonder that the first thing you’ll find on Mr. Urrea’s “About” page on his website is NPR’s designation of him as a “master storyteller with a rock and roll heart.”

In his books, Mr. Urrea unearths lives that have been buried. His writing is what he calls “bearing witness.” In the masterclass he held at Towson, he told us about—or, more accurately, performed—his own experiences that culminated into his identity as a storyteller. As he came to understandings he had not had before, he recognized the truths that his unique background uncovered and their need to be told. Sitting among students in a tightly-packed classroom, Mr. Urrea brought us with him into his past. He expressed intimately the story of his father’s unjust and tragic death. He confided in us. He trusted us with the responsibility of knowing the importance of his brother’s influence in The House Of Broken Angels, a novel written after his brother’s death. Mr. Urrea’s way of storytelling draws listeners into a lifelong promise.

He expertly weaves emotion and surprising humor in stories that sing of the lives of immigrants, Native people, women, and other folks who have been too often overshadowed by the dominant minority. The drive of Mr. Urrea’s life, as he made clear to us, is amplifying the voices of the influencers, the voices of the people who gave their love and passion and received nothing in return. That rock and roll heart beats for the lives of the oppressed, just like the music genre of the same name.

Luis Urrea brought to my attention the importance of your own story. It is already weaved intimately in the oppressed voices that call to writers. In class, one student asked about writing someone else’s story as a person who has not experienced what they have. Mr. Urrea asked us to do our due diligence in getting another’s story right. He handed the words to us like bricks we could use to build ourselves. Chuckling, he told us how he had once asked renowned indigenous author Linda Hogan to write The Hummingbird’s Daughter, a now-published novel with deep Native American and Mexican roots. He claimed his mind was too Western to write it himself. She waved her hand peacefully, and then she replied to him, “The Western mind is a fever. It will pass.”

The act of bearing witness can transcend our barriers if we commit with respect and love. Not only can this apply to others’ stories, our own stories deserve that due diligence, too.

The day Mr. Urrea came to Towson was a day I noticed my mind lost some grounding with reality. It may seem like a simple thing. About two months into the school semester was when Mr. Urrea held his masterclass, and I decided my regular class started at 4:00 (it actually started at 3:30). Conveniently, Mr. Urrea’s talk was scheduled until 3:45, and then I stayed until 4:00 as it ran over. I thought I’d only be a few minutes late, not a half hour. I came to understand that my own mind had tricked me. It has happened often, and it is always unnerving when it does. There have been times when I needed my memory. I needed to rely on it, to be there for the people who I care about most, who were depending on my memory in one of the most literal forms you might experience. I was a witness for the rape of someone I love. During pre-trial interviews, they asked me to recount what had happened. Instead of answering truthfully, faced with a gathering of legal workers, my vision blacked out, but I didn’t stop functioning. I ended up telling the story of my own rape, for the first time.

They dismissed me from the case. I was the only witness. I know it’s not my fault, and that this is the justice system we live with—but the rapist was charged for his drug possession, not for the rape. The justice system itself told someone I love that their rape didn’t happen, that their feelings were invalid. If I had been able to articulate and process my story before that moment, maybe I’d have been able to tell the victim’s. Perhaps telling my story in that moment wouldn’t have mattered. Telling our stories, and integrating our stories into the narrative and the understanding of our society, will.

Another revolutionary author, bell hooks, excavates in her fist-pumping title, Rock My Soul: Black People And Self Esteem, that the way in which we act and behave, especially in life’s throes of mundanity, has a crucial effect on our mental health and identity. During the masterclass, Mr. Urrea shared with us a lesson: an entire life is a river, and its tightest bends are where you’ll find the stories, where something either must change or must fail. The choice between embracing our story or suppressing it is in the ordinary, everyday choices and bends that we face. Building ourselves and our identities is in any opportunity to express and perform your story, your thoughts, your feelings.

***

Photo courtesy of Towson University