By: Maria Asimopoulos, Fiction Editor

A few days ago, my best friend Krupa texted me to tell me she was taking a break from her usual streaming routine to revisit Divergent, a book and film that were huge when we were teenagers. I told her it was an excellent choice and that I’d been itching to rewatch The Hunger Games. “I just did that too,” she said. “It hits a little harder in these times.”

Years ago, at the start of my undergraduate English program, I sat at a cheap desk in my dorm studying for Spring semester finals. I had been at it for hours, flipping through PowerPoints and crafting notecards instead of sleeping (which is arguably what I should have been doing at 5 a.m.). I’m now a senior, but this moment came back to me today, April 19, at the start of my fifth week under lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic. The contents of the notecards are the reason why.

In my hands were American literary movements from realism through postmodernism: time, space, history, and people, bundled up nicely into abbreviated bullet points and blue ink for me to study. I held literature’s reflection of the human condition in my hands, and I wondered what it looked like now, on that May morning in 2017. So I googled it.

Dystopian literature. A movement hadn’t been defined yet; critics went back and forth arguing whether we had moved beyond postmodernism to begin with, but a brave few suggested that dystopian fiction was our next stop on the literary wagon. Indeed, with booming franchises like Divergent and The Hunger Games so fresh in my memory, 18-year-old me could believe it. Authors were telling stories of environmental destruction, economic despair, and the collapse of society. With climate change and wealth inequality looming in the back of our collective consciousness (of course, these days I would argue that it’s more at the forefront), it is no wonder we had such a need for these stories.

And it’s no wonder that we feel such a powerful need to return to them now. Our economy is crumbling and, for many of us, the thought of participating in society makes us paranoid. We’ve become increasingly conscious of our bodies in relation to the world: the ways they function, their positioning around other people, the way we hold ourselves in grocery stores. We’re not being sorted into personality categories like characters in Divergent, nor are our children being rounded up to fight to the death as they are in The Hunger Games. But we are getting a front row seat to the exposure of vulnerabilities in our medical and financial infrastructures. We’re bearing witness to politicians’ blatant disregard for human life while we burn through our savings and apply desperately for unemployment that many will not receive. We’re video chatting with loved ones to express our condolences during funerals that have a mandated limit on how many people can mourn together. Dystopian.

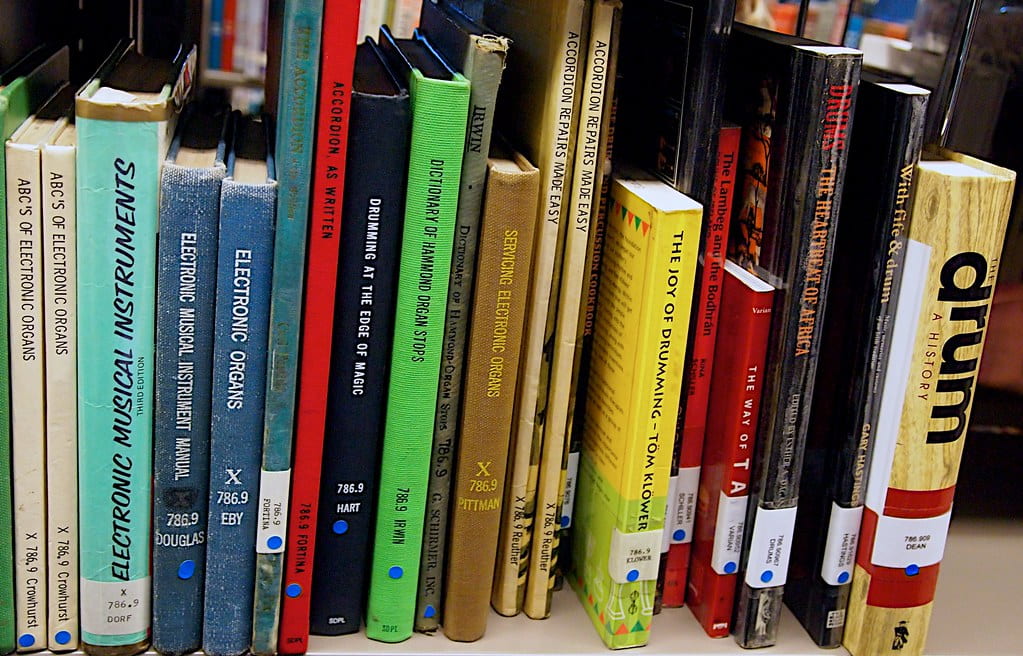

In all the time we spend at home, art is more critical in our modern lives than ever. Movies and TV can distract us from endless hours spent indoors. Never before have I seen quite so many people posting music recommendations on their social media. We can finally find moments to get to the endless reading list, books that have been glaring at us from our shelves for weeks, begging us to take a break from our busy schedules and open them. We can spend this strange time panicking, or we can spend it immersed in other worlds and stories. Many of us are choosing the latter.

If dystopian literature wasn’t where the bulk of critics thought we were moving a few years ago, perhaps it will be now. Brave New World has just re-entered my “to read” list on Goodreads. I’m going to keep on my vow to rewatch The Hunger Games—more than that, I’ve been itching to reread it, too, and I haven’t felt that urge about a YA novel since my mid-teens.

These are unprecedented times. It often feels as though we have more to worry about than we ever thought we could handle. But when a virus cracks the world wide open, maybe literature is just the thing we need to begin to fill in the gaps.