By: Christina Yang

Michelle and Doug meet for the first time at a Panera Bread in May. She has come straight from the eleven o’clock service at the Anglican Church, although her preference is Presbyterian.

“A churchgoer, huh? I’m a lapsed Catholic myself.” Doug takes a bite from the shiny waxed apple on his tray. “Hope that’s not a problem.”

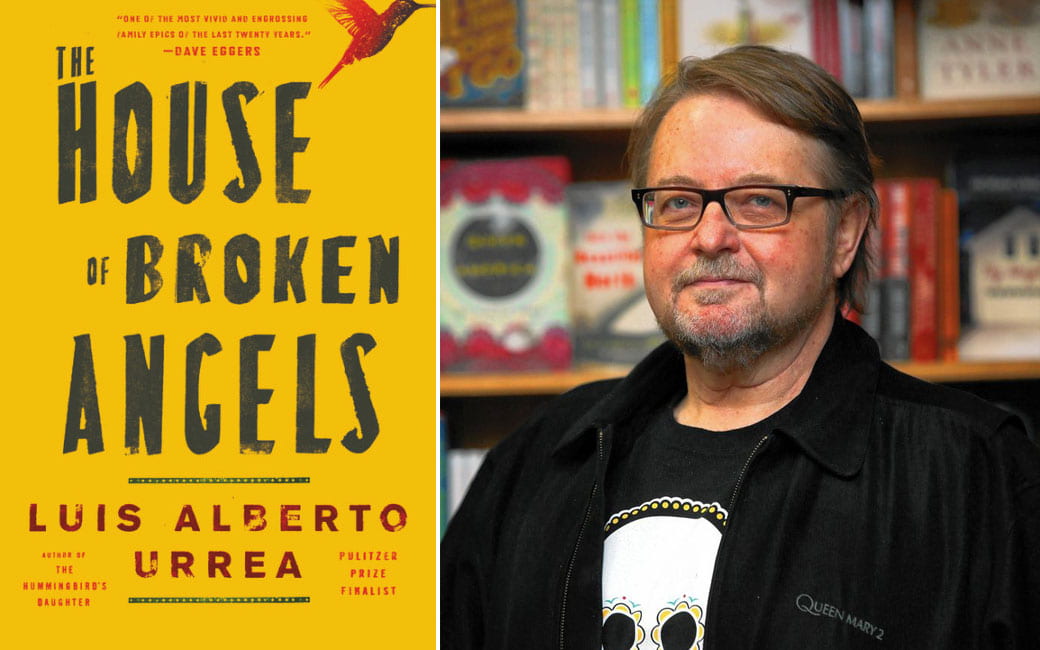

Michelle is recently thirty-five and new to Milwaukee. She is moon-faced and petite with skin so unblemished it looks oiled in certain lights. She is not unpleasant looking, but there is something about the unsmiling way she presents herself that seems to put people off or make them shy away from her. This is a closely guarded and deep source of pain. In her darkest moments, she worries that there is something seriously wrong with her. Michelle has matched with Doug on a dating website despite specifying an interest in Asian men only. This year, she finally decided to “put herself out there.” She hates how desperate that makes her sound, but she does not want to spend the rest of her life alone.

At first, Michelle corresponds with Doug over email. She learns that he is thirty-two and a native of the state. He does not own a cell phone. He’s only ever met one famous person in his entire life and that was Sylvester Stallone’s mother at a bookstore signing when he was eleven. She was wearing a white turban and bright pink lipstick that looked nearly fluorescent against her heavily tanned skin. Michelle thinks that these are weird details to remember, and even weirder that he’s sharing them with someone he’s presumably trying to impress. Which means he’s either an oddball or terrifically confident, both of which sound equally intriguing.

In person, Doug has a hulking build that has gone soft in the middle, and a non-descript pleasant look about him that feels appropriately Midwestern. When he looks at her, it’s with an intensity that she finds both flattering and discomfiting. Over lunch, he tells her that football was his entire life. He quarterbacked at a local college, but a shoulder injury his senior year ended his career. He’s an arborist now.

She asks him how he came to this particular profession.

“My uncle had a business. I used to work for him in the summer. Then he fell out of a dogwood. A freak accident.”

He tells her that dogwoods are not big trees. His uncle would regularly scale trees two, three times the height without ever having a problem. This one just happened to break both of his legs.

“That’s unfortunate.” She is deathly afraid of heights—just the subject upsets her stomach. She pushes aside the yogurt and granola parfait she’s eating.

She wants to know if he climbs trees too, and if so, why in the world wouldn’t he use a ladder or a crane?

The best arborists get into the tree if they can help it, he says. It’s a way to commune with the tree.

“Do you like poetry?” he asks.

Michelle shrugs. She was a chemistry major in college.

“Auden? William Carlos Williams? ‘I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox’?”

“Plums?”

“Climbing trees is the closest thing to poetry that I know.”

She leans back in her seat. “Huh.”

He asks her what she thinks of Milwaukee so far (clean and flat with many tall white people who say “gee” and “golly” without irony). He asks her how she is settling in at her new condo, the first piece of real estate she has ever purchased. She tells him that she is mostly unpacked, but largely unfurnished, which doesn’t bother her.

As they eat, she notices that he wipes his hands and mouth with a single napkin, which he folds neatly and tucks underneath the side of his plate between uses. He chews with his mouth closed and leans in when he’s speaking. If he’s worried that his breath is bad or that there is spinach stuck in his teeth, he doesn’t show it. She admires his ease. On the other hand, he wears a smirk on his face that puts her on the defensive, like he’s in on some private joke at her expense. She tells herself that maybe he can’t help it, the way some old people always look sad when it’s just gravity and sagging skin at work.

Then he makes a comment that changes her mind.

“You strike me as very, very organized,” he says.

“Excuse me?”

“Let me guess. You were the kid who never turned in an assignment late. When the teacher had you do just the odd numbered problems, you’d do the even-numbered ones too.”

“Hang on a minute.”

“Am I wrong?”

“I don’t like what you’re implying.” She sweeps her trash onto the tray and takes an angry sip of her water. She’s heard every single Chinese nerd stereotype, and she is not here for that. Another afternoon wasted when she could have been binge watching The Victory Garden on Netflix in her favorite pair of stretchy pants.

“I bet you are a magnificent speller.”

“What?”

“Spell apropos.”

He has uncapped his iced tea and watches her now with curiosity, the way you might poke at a puddle on the sidewalk out of boredom. To her surprise, she finds herself softening.

She spells apropos perfectly.

“See?” he says.

“I won a county-wide spelling bee in sixth grade,” she says.

“Now that is something,” he says.

#

When Michelle graduated from college, she moved to Taipei without a plan. This disappointed her parents, who had their whole church back home in New Jersey pray for her. In Taipei, she found work as an English-language tutor and later a copywriter at a plastics company. One day, she ran into a distant cousin on her father’s side who helped her land a job at a company that manufactured and sold chemistry supplies to laboratories, universities, and corporations. Now, ten years later, she is second-in-command to the CEO. It sounds impressive except that the organization consists entirely of ten people. Six months ago, she was tasked with establishing an American outpost of the company in Milwaukee. She is responsible for everything from staffing and setting up payroll and benefits all the way down to ordering the office furniture. Each day she lives in mortal fear of royally screwing something up.

She communicates with her parents mostly via email because the thought of speaking with them over the phone infuriates her. They’d hoped she might go into ministry, attend a seminary, marry a pastor. Despite being valedictorian of her high school class and then graduating magna cum laude from Cornell, they never thought to congratulate her. Earthly accomplishments should mean nothing to us as Christians, they’d say.

Her anger over the years has hardened into a jagged nugget lodged firmly inside of her chest, and when she reads the Bible and prays for forgiveness, she hears nothing. She tries to conjure up sermons about surrendering yourself to the Lord, all the while fighting the urge to balk at the notion. Nothing works, but it doesn’t matter. She refuses to give up on her faith. She’s invested too much in it already, like an insurance policy she has to keep current in case she ever needs to cash out.

#

On their next date, Michelle invites Doug to her place. She’s prepared a bastardized version of a noodle dish her mother used to serve the family, a dish that she’s developed a newfound appreciation of since living in Taipei.

They perch on cushions on the floor, bowls in their laps. He makes the kind of small talk that she would find patronizing coming from anyone else, but there is something playful in the way he does it. At one point, he stretches his feet through dingy white athletic socks, and she feels a flush of embarrassment for having asked him to take off his shoes at the door, like she’d asked him to hang up his underwear.

After dinner, he picks up the books she’s borrowed from the library—books on retirement planning and achieving financial independence. He flips through the pages and returns the books to the coffee table without comment. She notices how nice his hands are. His cuticles are smooth and even, not what she would have expected from someone who performs manual labor all day.

“Do you want to see my garden?” she says.

They step out onto the patio, which is seven floors up, high enough that the chatter of patrons across the street, dining outside beneath the heat lamps at the microbrewery, is muted. It’s a clear, breezeless night. A motorcycle roars down the street.

She shows him the potted tomatoes, lettuces, bell peppers, and cucumbers that she started indoors from seed.

“Wow,” he says. “The things you can grow in the middle of the city.”

She explains the heirloom varieties of tomatoes she’s planted, why she’s chosen these particular strains. She plans to experiment with different soil drainage methods to see which ones encourage the most robust growth. This is the kind of nerd stuff that excites her and keeps her up at night, her brain churning through various theories.

He looks at her with an amused expression, like a grown-up humoring a child. She breaks off in mid-sentence.

“What?” she says, annoyed.

“It’s just that I’ve never met someone so passionate about dirt and vegetables before.”

“Well, I’ve never met someone who climbs trees for a living.”

“I guess we’re even then.” He grins and places a hand on the small of her back. His touch sends an unexpected current through her that she finds unnerving, and she has to take a second to gird herself again.

For religious reasons, Michelle does not believe in premarital sex. She has only ever kissed a handful of men. One was a complete stranger, which she found surprised even herself—a Swedish businessman on a transatlantic flight who seemed strangely fixated on her pores. She’d been feeling maudlin about an upcoming birthday and had had too much to drink in the airline lounge beforehand. In her early twenties, she’d engaged in some intense dry humping with a boyfriend she thought she might marry. Over the years, she has watched friends pair up and procreate, a sifting away process which fills her with longing and sadness, the depths of which have turned her defiant. She teaches herself how to change the oil in her car, she hardly wears makeup, and she will negotiate the price of an appliance, an armchair, or whatever until the other person is in tears. She refuses to look weak because she’s single.

Doug gestures toward a series of shallow plastic bins stacked on top of each other.

“What’s this?” he asks.

“It’s my worm factory,” she says, taking the opportunity to move away from his reach. “You start with your worms and strips of newspaper and then you feed them vegetable scraps and coffee grounds, and they turn it all into dirt. It’s called black gold.”

She has done an extensive amount of research on the subject. The worm factory was the first thing she purchased when she moved to Milwaukee, but she has been adherent to the zero-waste concept for several years now. It’s a comforting thought, the idea of leaving little-to-nothing behind.

He asks her where she gets the worms. She tells him that she buys them online from a farm in California. “They ship early in the week, so they don’t die on the way.” She feels a tug of sympathy as she pictures the worms tumbling around in a box in the dark over hundreds of miles.

She pokes at a cluster of worms resting in a mound of dried-out carrot peels. They squirm and stretch.

“Say hello,” she says, smiling down at them affectionately.

“Hello,” he says, and waves.

#

The following Monday, she calls her older sister, Allison, from the office. She’s working late again. It’s eight, and she’s finally taking a break to eat dinner at her desk—leftovers scraped together from her fridge—while the janitor empties the waste baskets and vacuums around her feet.

“How are things in Wisconsin? Eating a lot of cheese?” Allison asks.

“No, but I’m drinking a lot of beer.”

“Better not tell Mom and Dad.”

They laugh. Allison has a better relationship with their parents. She is a pediatric dentist, and it’s Brad who stays home with their sons, packs the lunches, straightens up the house. Together, Brad and Allison are always scheming over their next vacation, debating whether the kids are old enough to be left with Brad’s parents so that they can go on a couples safari instead of their usual weekend excursion to some germy children’s museum.

“Are you completely surrounded by white people?” Allison says.

“It’s not that bad. There’s a girl at my church who’s Korean,” Michelle adds, “But she’s adopted.”

“Well, that’s not the same,” Allison says, and Michelle has to agree. Then Allison asks, “Are you happy?”

What her sister really wants to know is if she’s lonely. Michelle tells her she’s holding up. What she doesn’t say is that there are some days when she’s peeing at work and staring at the drab metal stall door and wondering if she’s made a mistake moving here. No one is rude or mean to her. Yet they circle her with unfailing politeness, as though they don’t know what to make of her. She finds this incredibly alienating.

She worries that she’ll never feel at home here. Maybe she’ll never feel at home anywhere. Even in Taipei, they knew her for what she was: an outsider. She never had to utter a single word. They recognized it in her choice of clothing, the way she styled her hair, even the state of her teeth.

Allison tells her now that she can always move. “You’re not trapped. Though selling the condo will be a pain,” she concedes.

“I’m not worried about that,” Michelle says. “It’s my worms. What would I do with them? How would I take them with me?”

“What do you mean what would you do with your worms?”

She has to explain the worm factory again, how it works, the time and patience it’s taken to cultivate them so far.

“Leave them. Outside. In the dirt.” Michelle can almost hear Allison shaking her head on the other end of the line. “Of all things.”

#

Doug calls on Friday night after nine. They meet in front of her building. Even at this hour, the temperature hasn’t dropped noticeably, and she’s warm, feeling overdressed in jeans. The sounds of the freeway are a constant background hum. Music pours from restaurant speakers and mingles with the sound of laughter and shouts, the unwinding of another work week. Doug’s hair is damp from a shower. She can smell his soap, heightened by the warmth of his skin.

As they start to walk, he points to the maple tree by the building sign out front and says, “That thing’s not looking so hot. You might want to mention it to the super.”

It looks fine to her, maybe a little tilted. “Okay,” she says without really meaning it.

They cross the street. She follows him down a narrow path she’s never noticed before until they emerge onto a wider asphalt path lit every so often by streetlights.

“I had no idea this was here,” she says, amazed. Pedestrians and cyclists weave their way left and right. In the distance, she can hear the sound of water lapping, smoothing away the rough edges of the night.

He steers her to a bench and produces two bottles of beer from his backpack. He pops open the tops and hands her one. It’s cold and slick from condensation.

“Spotted Cow,” he says. “Our finest.”

She takes a sip.

“You can only get it in Wisconsin,” he says.

There’s pride in his voice, like he brewed the beer himself. She holds the bottle up and pretends to admire its contents. She doesn’t know the first thing about beer, or care. People are funny, though, how strongly they associate themselves with the things of where they live, how easily offended they get if you don’t act properly impressed.

“It’s good,” she says.

“Now you’re one of us.”

He clinks his bottle against hers. She can’t help but smile as she takes another sip.

He rubs his chin. “I had this dream last night. I was being chased by a bunch of clowns. I locked myself into a room to get away from them, but I don’t know what was worse, the clowns or the room.”

“Did you escape?”

“I don’t know. I woke up before I could find out.”

“They definitely got you then,” she says, teasing. But he’s not listening. He pinches her earlobe gently between his thumb and forefinger.

“What are you doing?” she asks.

He leans over and whispers into her ear, “You’re pretty.”

She laughs because she doesn’t believe him. But the words still make her happy.

They finish their beers and walk some more. Their hips knock together lightly at intervals. Michelle tells him about an order at work for 100,000 pipettes. The order is stuck in customs, and she’ll have to contact the German embassy on Monday to try to get it unstuck. Doug looks at her intently, like he’s waiting for her to say something entertaining or amusing. But she’s not one for current affairs or politics or jokes. Then his mouth is on hers, their teeth bump, ouch.

After a minute, she says, “Can we try that again?”

#

Later that night, she can’t sleep. She walks out onto the balcony to check on her worms. They’re hiding in the dirt, which is now festooned with curled up, yellowed leaves of kale.

She sends a text message to Allison to see if she’s up, but there’s no reply.

She checks her email. There’s a message from Doug.

He asks her if she’s ever been in the middle of a dream only to realize she was actually inside of it. That’s what happened to me with the clowns the other night, he writes. I was running from them, and then suddenly I was watching myself running from them. All of the fear and panic I had just disappeared because I knew they couldn’t actually hurt me. He writes, I’m not here to mess around. I want to get married, have kids, get a dog, all of it. I don’t know if it’ll be you, but maybe it will be, and if so, wouldn’t that be cool?

She writes back.

I can’t remember half of my dreams. They slip away from me most of the time, and sometimes that’s a relief and sometimes it’s sad because I suspect they are good, the ones that escape. Come to think of it, it seems that the ones I remember are the dreams that frighten me or make no sense, like I’ve got to paddle a boat across a river filled with Cheerios and I’m panicking because my bladder feels like it’s about to burst. I think it must say something about my personality, that I’m cynical or too high-strung or glass half-empty, but I’d like to think that I’m better than that. That dreams are a repository for all of the negative things we want to bundle up and expel so that what’s left behind is just the good.

She thinks she should write something else in response to the other thing he said, but she doesn’t feel ready to articulate something so intimate. Instead, she sends off what she has and in the morning finds another email from him.

That there, he writes, is poetry.

#

Over the next several weeks, they cook meals together and watch movies on her couch with the lights off and the windows open. He massages her feet. She’s embarrassed by the fact that her nails are unpainted and her heels are white and flaky. When she tries to pull away, he plunks her feet back onto his lap without glancing away from the screen.

He tags along on really boring errands to the drugstore for dental floss or multi-vitamins. She finds his corny jokes oddly delightful, the way he tells them with a wink.

One day, she comes home from work to find him kneeling outside the front door to her unit, going at the hinges with an old rag and a bottle of olive oil. They were squeaking, he explains.

The fissures start to present themselves, too. It hasn’t quite been two months. He doesn’t clean off the knife when he switches between the peanut butter and the jelly jars. She has to constantly remind him to take his shoes off at the door, and she can’t help but think in the back of her mind that if it’s this hard now, how hard will it be later? Sometimes, she can tell that he doesn’t get her humor, but he smiles tolerantly as though it might hit him at some future point if he gives it enough time.

On one particular evening, he complains about the temperature in the condo and turns up the air conditioning, which sets them bickering. She doesn’t think it’s hot at all. He says he can’t concentrate. What do you need to concentrate on, she wants to know? He tells her she doesn’t need to be so cheap, which makes her so mad she orders him to leave.

He does, but then comes back an hour later. She won’t let him upstairs. She’ll only talk to him through the intercom.

“I’m sorry,” he says.

“I don’t like being called cheap.”

“Why?” he asks.

“My parents refused to buy a dryer for our clothes when I was a kid. We had to hang them up to dry on a line in the basement, and sometimes they ended up smelling like mildew, and I got made fun of for it. Even when I’m old, or I’ve become successful and rich and famous, it won’t matter. That’s the kind of stuff that sticks with you forever.”

The intercom crackles as he disengages his finger. All she’s left with is an unbearable silence.

“Hello?”

“I was engaged to this girl in college, and then I wrecked my shoulder. I was a big deal, and the next day, I wasn’t. She broke it off, and that messed with my head. Did she love me for me or was it because of what I could do on the field? What am I without football?”

Outside, a gusting wind has started. It rattles the tree branches. She remembers the maple tree that Doug had pointed out, and apprehension grabs hold of her.

“Then I started thinking about it the other way around,” he says. “What am I with football? I’m still me either way, right? I can throw or I can’t throw.”

Michelle is silent for a moment.

“I wish I had your confidence,” she says.

“You don’t need my confidence.”

She shrugs. “Yeah. Well. I don’t know about that.”

“I think you’re great,” he says in a way that doesn’t invite argument.

He tells her that he’s leaving her something. Downstairs, she finds a tied-off plastic shopping bag filled with old food scraps for her worms. She opens the bag to inspect the contents. She finds apple cores and banana peels, the top of a fennel bulb and ginger root shavings, plus a few things she can’t identify. It gets her a bit choked up, these gifts he’s given her.

#

Allison calls early Sunday morning while Michelle is brushing her teeth and still waking up.

“Brad and I are getting a divorce,” she announces.

Michelle is too stunned to respond. By now, she’s witnessed the break-up of a few scattered marriages, but the thought of her sister and Brad splitting up is unfathomable. She can’t think of two people more suited for each other. Even their spats have an air of predictability about them, a promise not to get too messy or spill outside a certain confine.

“Are you okay?” Michelle finally says.

“It was a long time coming,” Allison explains, her voice even. “He’s living in the basement for now so the kids have no idea. Also, don’t say anything to Mom and Dad. You know how bad that conversation’s going to go. I’ve got to figure out my approach first before I break the news to them.”

Michelle pauses and then says, “You didn’t answer my question.”

A funny noise travels across the line, like the gurgling sound of someone drowning.

After they hang up and for the rest of the afternoon, Michelle feels unsettled. She washes the dishes and manages to break a glass in the process. She sweeps the pieces into a dustpan and watches them tumble into the abyss of the garbage can. If her sister’s separation from her husband was a long time coming, then why hadn’t Michelle seen it? The question keeps playing in her mind as she tries to watch television or read a book, but she can’t make sense of any of it.

In the evening, she and Doug go to the big music festival in the city. Lights festoon the trees, and the sweet, hoppy scent of beer fills the air. The mosquitoes bother her legs, but she slaps them away. They find an empty square of grass and set up their blanket. Doug says he’s going to find food, maybe one of those sausage dogs with peppers and onions and he asks Michelle if she wants one too, but she says no. The band on stage finishes its set and another one takes the stage. A small-yet-determined crowd surges forward as the next band launches into a song that everyone seems to recognize except for her.

Doug returns with his sandwich and a cola. The air has grown heavy with humidity. The music is too loud, and she can feel a headache coming on. He eats in silence, oblivious to her sour mood. When the next performer comes on, he jumps to his feet in excitement. The first several chords rip through the night and the drummer starts pounding on his kit, the music quickly building towards a frenzy.

Doug leans down and shouts into her ear, “I love this band!”

He wags his head to the beat like a dog shaking rain from its fur. His feet move, too, but as though on a tape delay from his upper body.

He reaches down. “Dance with me.”

“No, thanks.”

“Come on. I’m already making a fool of myself. Might as well join me.”

He pulls her to her feet and puts his arms around her, bringing her close. He presses his forehead to hers so that she can feel the sweat sliding against her skin. “Hello, beautiful,” he says.

She tries to turn away, but he forces eye contact. With his gaze, he tries to communicate something weighty and significant, something that supersedes words, and she feels herself suffocating underneath the burden. All around them are other couples—holding hands, laughing, kissing—doing what people in love do. Except that beneath the happy exterior lies an invisible interior life that’s muddled and messy and conflicted.

Doug is still studying her with that painfully earnest look. Wanting something she can’t live up to, and neither can he, she realizes with a sinking feeling. She starts to panic.

“Let me go,” she says, nearly gasping.

She makes an excuse about the bathroom.

He calls after her, but she ignores him. She hurries towards the signs directing her to the Porta Potties and finds a long line. Her place isn’t too far from here. She decides to walk back and use her own toilet. Just to get some air, she tells herself. She cuts across the green, which has grown slippery. She spots the maple tree in the distance and uses it to guide her back home. Still standing, she thinks to herself when she passes underneath its canopy.

Back inside the condo, she takes her shoes off and sets them neatly by the door. She hangs her purse up on the hook inside the closet and breathes a deep sigh of relief. She uses the bathroom and then goes to the balcony to find her worms hiding from sight. She pokes at the loam, which sets the soil line to undulating.

“Earthquake,” she whispers.

She lays down on the sofa, thinking how tired she is. She’ll just rest for a minute. Traffic is picking up outside. People are leaving the festival, jamming up all of the major arteries of the city. She thinks about Doug still waiting for her, and suddenly her legs feel like lead. She should go back for him, knowing that she won’t and knowing that that’s a crummy thing to do to him. She’s safe here cocooned into the cushions.

Behind her closed eyelids, she sees lights flashing green, yellow, red.

#

The next day, when Michelle returns home from work and unlocks the door, the first thing that hits her is the sweltering heat. The heat index is forecasted to be well into the hundreds. She plays around with the thermostat, stabbing at the buttons, but nothing happens. She calls the super. He tells her that a good portion of the building has been down, and that they’re working on getting the air conditioning back up again.

When she hangs up, her body goes numb from pure dread. She runs to the worm bin, which she’d dragged inside the previous night, only to find every last one of her worms has died.

She calls Doug, but he doesn’t pick up. When she hears his voice over the answering machine, a floodgate opens inside of her, and she begins to sob. She stumbles over her words.

“Please come. Quick.”

Later that night when she doesn’t hear from him, she writes him an email.

I’m sorry about leaving you at the festival. You’re mad, aren’t you?

She looks around the pristine condo that she cleaned just two days before. The sofa still smells like new upholstery. The sun shines through the blinds and illuminates not even one speck of dust. She has never imagined she could feel this utterly alone.

She strips down to her underwear, pulls back the comforter and lays down on top of the sheets. She presses a bag of frozen corn to her forehead as her only relief. She should leave the house, maybe walk to the bar across the street and get a cold drink, but the task of pulling herself together and looking presentable to the world seems insurmountable at the moment.

Two days pass. When she goes to work in the morning, she finally finds a response from Doug.

I’m sorry about your worms, but I can’t do this anymore. We want different things. Actually, I don’t know what you want, and I don’t think you do, either. You need to figure it out. Not for me, but for you.

His words sting. That’s it? She calls his apartment, but there is no answer. She tells her boss that she needs to take an early lunch break. She drives to his place and knocks on his door, but no one answers. The curtains are drawn.

She dials him at intervals throughout the day.

After work, she drives to his place again. She sits in her car and eats a vegetarian burrito, then manages to doze off, only to wake an hour later with a start. The sun is setting and the sky is the purple of bruised fruit. She feels a terrible throbbing in her chest that simply won’t stop.

Doug’s apartment is completely dark.

She’d pictured a much different future for her worms, one in which they grew fat and long and sleek, in which the rich, dark soil multiplied day after day until it could hardly be contained.

The next day, she replies to Doug’s email.

Remember what you told me that night, about how you thought your life was going one way and then it went another way? I have a hard time negotiating the turns. I want a map, but there isn’t one, and then I get lost. Where are you now, Doug? Please call me.

She sends the email off, and then goes for a run. She veers down an empty side street off her usual route and passes a consignment store, a tax office, and a piano tuner’s shop, all closed because it’s Sunday. At the end of the street a homeless man squats with a large dog at his feet, the kind they warn you will bite your face off if you’re not careful. This one simply looks bored and listless. It’s too late to turn around though. The man lumbers to his feet as she passes, and her throat constricts with fear. She picks up her pace.

“Don’t be scared, honey,” he says. She hazards a glance at his face as she runs past. His breath smells boozy, and he flashes a big smile to reveal several missing teeth. Suddenly, she’s reminded of the clowns from Doug’s dream. After she’s passed him, she looks back to see the man raise a bottle in salute. She recognizes the Spotted Cow logo, and suddenly her fear vanishes. Tears prick her eyes and blur the sidewalk in front of her.

Back home, she cleans out the worm factory. She drops the dead creatures over the side of the balcony. The first one lands on the sidewalk below before she realizes that it’ll get crushed by resident foot traffic, a thought too heartbreaking for her to bear. She flings the rest of the worms into the air one by one like confetti. A celebration of their lives, she imagines herself explaining to an invisible audience. The worms land in the grass and in the shrubs and in the canopy of the nearby trees.

Below, the maple tree has taken on a hangdog appearance. Its leaves are spotted, and the edges are brittle looking and curled. It’s finally obvious to her how sick it is.

#

Over the next week, she watches the evening news after work. At the office, she refreshes the local news website. She listens to the radio everywhere she goes. If there is a car accident or a murderous rampage or news of a body fished out of a lake, her body tenses up until she learns that it’s not Doug, but someone else.

She hears the bad news of everyone everywhere within a fifty-mile radius, but there is still no sign of Doug.

Some things aren’t meant to be, she thinks to herself, and the disappointment is both familiar and a relief.

A few days later, she comes home at dusk. She’s worked late yet again, and her brain feels like mush. The temperature has finally come down to the point where she is shivering a little in her sleeveless top. She begins the trek up the stairs outside of her condo complex and finds herself startled by the sound of a chainsaw coming to life. She becomes aware of a bright orange cordon set up around the perimeter of the diseased maple tree.

She looks up. Doug is in a knit wool skull cap in the middle of the tree’s canopy, his legs hugging a thick, gnarled branch. There’s a chainsaw in one hand, while the other hand grips the branch that he’s just cut.

“Doug? What are you doing?” Michelle says.

He doesn’t answer her. He inches along the branch, moving farther from the trunk. The branch sags underneath his weight. There is a happy hour gathering on the rooftop terrace of the building. Young professionals in loosened ties and creamy silk blouses gather at the railing to watch Doug work. Some of them whistle and jeer, which makes Doug’s lips thin with concentration, and Michelle’s heart jump up into her throat.

She wants them all to shut up. She feels lightheaded all of a sudden, seeing him so high up like that. She is afraid she’s going to vomit at any minute.

A young couple with a small child walk by. The child, when he catches a glimpse of Doug in the tree, refuses to take another step. More and more people gather on the sidewalk like one giant ball of lint.

“Doug. Please come down.” She tries to keep her voice even and calm.

“Your super hired me to take care of this tree.”

“You’re scaring me. I don’t like heights.”

“I’ve got a job to do, Michelle. So, let me do it.”

“We need to talk.”

Doug says, “If it’s the trunk that’s damaged, it will be nearly impossible to save the tree. From what I can tell, though, it’s just a branch or two. That means there’s hope.” He starts the chainsaw back up again, and it bucks in his hand, making the entire branch he is wrapped around shudder along with it. The crowd gasps.

He shouts something that gets drowned out by the sound of the chainsaw. He brings his arm down and the chainsaw along with it. One of the smaller branches is now down on the ground.

“I can save this tree, Michelle. Do you believe me?”

She is unable to speak. Her legs have turned to water. Something inside of her unclenches. Danger pulses through the air. It electrifies her, opens up her lungs.

“Yes,” she says.

“What’s that?”

She raises her voice. “I said, yes!”

He cuts power to the chainsaw and cups a hand to his ear. “I can’t hear you,” he says at the same time she says yes again. This time her answer comes out as a shout that carries across to every onlooker on the rooftop terrace and sidewalk. It travels to the residents of the various units who have opened their windows and are leaning out to watch.

“Yes!” She says it again at the top of her lungs without hesitation or shame. “You can do this!”

He looks down at her from the tree. Their eyes meet and hold for a second. He inches backward and starts the chainsaw back up. He goes to work. Branches pop and crack and fall to the ground. Parents hold their children closer. The sun shifts imperceptibly in the sky.

Doug has worked his way to the trunk, and now he stands at a V-intersection where the trunk splits into two main arteries. He must grip the chainsaw with both hands and successfully take down the last branch, which is as thick as Michelle’s waist. He braces his body against one side of the trunk. He lifts the saw above his head. She readies herself, waiting for him to swing the saw down like a sledgehammer. Instead, he touches the blade to the wood with a gentleness and tenderness that she doesn’t see coming at all. The saw whirs and spins and grinds for one minute and then two. It keeps going. It seems to her as though there is no progress being made, even as sawdust floats to the base of the trunk. Then finally there comes a deep groan as the wood begins to crack and separate, a moment when it teeters and hangs. Everyone holds their breath. All the commotion of the city seems to shut off. There is one final resounding break, a thud, and the branch is down.

Doug’s body relaxes into the tree. Michelle closes her eyes in relief. The evening swells with the sound of cheering.

#