by Regina Waters

Matti Ben-Lev is a queer nonfiction writer and poet from Baltimore, Maryland. He has been published by McSweeney’s, Rumpus, X-R-A-Y, HAD, Jake lit mag, and more. Matti was a part of Grub Street staff for Volume 72 and has contributed to Volume 74 and Grub Street Online. He is currently pursuing his MFA in nonfiction from George Mason University where he is the assistant nonfiction editor for their intersectional feminist literary magazine, So To Speak. I had the pleasure of interviewing Matti about how his creative nonfiction work “Phosphene,” published in Vol. 74, came to be.

This interview was conducted over Zoom by Regina Waters and was transcribed and edited for clarity and length.

Regina Waters: What inspired you to write “Phosphene”?

Matti Ben-Lev: I have been working for the better part of three years on a memoir that largely centers my mom and our Greek and Jewish heritage. I tend to write in vignettes, regardless of the size of my project. I write in sections and collect memories, and a couple of the things that I wrote for that memoir I really liked and pulled them out to create flash pieces with. “Phosphene” was one of them.

For the arc of the memoir I’m working on, I was trying to show moments where I could pack context into a scene, rather than context dumping. “Phosphene” was a pretty foundational piece because I realized I can capture so many things. The original piece was longer because it was meant for this other work of capturing something about heritage, something about my grandfather, and the idea of passing something down.

My grandfather taught my mom how to take a picture with her mind. Originally, I had it in there, but with flash I could capture the context of when this was happening and the context of myself in relation to my sister and my mom, and convey such a vivid memory. So many memories are subjective that we can doubt them, and that memory, because of how my mom taught me to remember it, stands out so vividly—I feel like that memory is stronger than something I experienced a month ago. That’s the inspiration for that piece: It was a way to fit context into a scene. I love vivid imagery and language, and when I was editing it to flash, because it was such a limited space, every little piece had to do something for the work.

When it comes to flash, you want there to be a turn and every single sentence and word to serve the piece and the subject to fit in such a tight container like that.

RW: You shortened “Phosphene” for publication. Can you tell us about your writing process?

MBL: I went through and made sure that every single sentence served what I was trying to say. I also had a couple more section breaks because there was more context in the original. I was really asking myself, “What can I delete that will allow me to still tell the same story of this memory?” When I got down to a certain point, I asked myself, “What context is in my larger project that contextualized this piece that I need to still do that work in this piece?”

I was mainly stuck where there was a little bit more explanation about certain things like Varkiza, but I essentially just tried to capture that moment with as little context as possible. So, it’s trying to be one powerful scene where there’s a little context as is necessary to understand the piece.

I’ve heard this from flash fiction seminars I’ve been in: the narrator or the protagonist is supposed to be different from the one who started the narrative. I was thinking about that a little bit as well, like, “how can I imply that there’s a difference?” That implication is zooming out. Some people would call it the turn. Like, “oh, this is a memory that I still have very vividly, where I can remember the sounds and the smells.” You look at the name “Phosphene,” something that when I close my eyes I can still picture, and so I was trying to do that work in a flash piece because that work was already done or going to be done in a longer work.

RW: What craft elements did you implement in Phosphene after learning them from your time with lit mags?

MBL: This piece was written before I started working for So To Speak, but I was leaning on the imagery. One of the things I learned from a bunch of different sources—like Grub Street, being a poetry editor—is the reliance and importance of really strong imagery that sticks and really surprising language in that imagery. I don’t think that this piece was heavily influenced by what I saw. I think if I were to write flash today, it would be very influenced by what I’ve read in So To Speak.

RW: “Phosphene” relies on nostalgia and imagery. How do you typically write nostalgia? Did this piece require a different approach?

MBL: I think with nostalgia it’s very easy to wane into the overly sentimental and overly emotional. While writing should be emotional, you need to understand what’s going on, and it needs to be able to make the reader develop that emotion you’re writing. Especially in flash, where so much of it happens in the action. You want the reader to kind of come to this specific emotion or sense on their own.

George Mason has this book festival every year, and fiction writer Lydi Conklin came and someone asked them, “What was one of the things you wanted the reader to feel?” Lydi said they wanted their readers to cry. And so, somebody asked a follow-up question of, “How do you make a reader cry?” And Lydi said that telling a reader “This character cried,” will never be as impactful as that character holding in all of their emotion and desperately trying to not cry and bottling it up. The action of crying isn’t particularly surprising, and the reader won’t need to cry because the character is doing that work for them. Lydi’s like, “How do I make the writer do the work for the character?” When I was writing “Phosphene,” I didn’t want to wane into the overly sentimental. I wanted to establish the importance of this memory by highlighting its vividness, not by telling you how I felt. There’s room for that interiority in longer nonfiction, but not much when you have a limited space. I was thinking, “I want to hit hard, I want to hit quickly, I want the reader to feel a certain emotion, and I don’t want to tell them this is what I felt.” For example, with the line, “we’re getting some time together, we haven’t had much since my sister was born,” I’m establishing the context of the importance of this memory without leaning into the overly sentimental or telling you I am being nostalgic.

RW: In the first sentence, you set the scene and introduce the main characters as you and your mother. Why did you introduce these two main characters in the first sentence, rather than the second sentence?

MBL: When you’re writing in such a small space, you need to give all of the context up front as quickly as lyrically possible. I wanted to establish where we were and who we were early, because I’ve read loads of flash, a lot of which I thought was pretty unsuccessful. One of the big pieces that is missing is not establishing context really early. Context needs to be really early, even in longer pieces.

I recently submitted a standalone essay to one of my professors, and in the second paragraph I give introductory context. He literally drew a circle around it and said it needed to be in the first few sentences. This was a full 20-page essay. He’s like, “no, first paragraph.” I’m not saying I wholeheartedly agree with that, but in a piece like “Phosphene,” you want the reader to want to spend time with the narrator, even in such a small space. It doesn’t mean they have to root for the narrator, but you want them to feel like, “this is someone that I want to spend the next 500 words with. I’m going to spend the next couple pages with them.” Part of that is giving that context up front. So, I was intentional when I said “overlooking the rocky beach in Varkiza.” I’m not saying a rocky beach, I’m saying the rocky beach. I’m already setting context, I’m already trying to indicate, “this is a place that I have gone with my mother previously.”

I’m trying to give you my age, and then sensory details to ground you before I go into the narrative, and I want to give that information as quickly as possible so I don’t lose the reader. I had to edit a piece for it to be a flash piece, and I asked myself what context needs to be given. I thought I should put that context in the first two sentences. That was the technical thinking.

I always think of that poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams: “so much depends / upon / a red wheel / barrow / glazed with rain / water / beside the white / chickens.” It could be “my family depends upon…,” “my livelihood depends upon…,” but it is “so much depends / upon / a red wheelbarrow.” I always think of those lines and the idea of the specificity of the red wheelbarrow and the abstract of the words “so much.” So much depends on it. I think about that a lot when I’m writing: “How do I leave that space open for the reader to fill and seek with their own mind?” That’s what I was thinking when I was writing “the rocky beach,” rather than “a beach in Varkiza.” I wanted to ground the reader and invite them to imagine there is one rocky beach in Varkiza, even though it’s not true.

RW: You’ve personified the ocean by writing, “the azure waves pulling in so fiercely it appeared they’d never release, and then thrusting water toward the rocks like a hug—holding tight and letting go.” Your imagery is evocative and imaginative and resembles the coming and going of memory and images. How did you know that you wanted to use the ocean as a vessel to convey this feeling?

MBL: Pretty immediately I realized I wanted to personify the ocean. Emotion between child and parent is not surprising. You can do it really well, but it doesn’t really subvert expectations. So, I was thinking about some of the work that I would do between my narrator and myself and my mom, and how I can put that relationship in imagery. I think when you’re working with flash there’s not as much room for that exposition or interiority. So how do I put that power and meaning onto something bigger? For me, and I think for a lot of people, there’s already something parental about the ocean, even maternal.

The waves receding and pushing back can mimic a lot of relationships. And I was thinking, “Does it mimic this relationship? How can I make it do that work?” It’s almost like the giving and pulling back of affection and love and connection and all the other things that go into any relationship. There is a push and there are moments where we’re on, moments where we’re off. So, I wanted to do that work and demonstrate that relationship without telling you, “Here’s what it felt like when I was a child, here’s this, and this and this happening.” How can I put that work on something much bigger than us that I can use imagery to paint in a beautiful way?

So, personifying the ocean came pretty much the moment I started writing this. I realized I wanted the ocean to represent parts of this relationship, so I don’t have to say it. Even down to the end, “thrusting toward the rocks like a hug—holding tight and letting go,” I was thinking that would be more impactful than, “like a hug from my mom—holding tight and letting go.” If I just went with that image, I want the final image to be the water crashing on the rocks and pulling back and repeating this cycle, and then to connect point A to B. The ending also came really early for me. I wanted to put this feeling on this water, and this motion, and this action. The last image that I leave readers with is not my mom and I hugging, it’s the water crashing and saying, “This is what it’s about. This is what I’m pointing to.”

RW: Since you established the sea as a main image, what is your relationship with the sea and what does it represent to you as a writer?

MBL: This particular beach represents a lot to me as a human, rather than the sea. When I was a kid, I would go to Varkiza, my grandparents lived there; my whole mom’s side of the family is Greek, and pretty much every summer up until I was 13, we would go and stay in Varkiza. Sometimes for a month or two. I would go to this beach every single day. And there’s no sand—it’s all rocks and it’s free and it’s hard to navigate, and there are so many memories there.

I recently wrote an essay, which I hope to get published soon, about my grandfather. He would take me to that beach every single day. I would stare at that water, and I would jump off this huge rock that you can kind of launch yourself off. My mom really did not want me to do it when I was a kid. I did it anyway. She ended up telling me she did the exact same thing as a kid: Her mom did not want her to jump off that rock, and she did it anyway. And so it’s really this beach in particular. I have so many powerful moments with this beach. I look at it as a setting that can do a lot of work for me because in my life it’s done a lot of work for me.This is a meaningful place where a lot of my connection with family and heritage comes in. So, I think whatever setting we can use as something that’s impactful to us and our story, I think we use.

RW: You have a lot of dialogue for a flash nonfiction piece. How did you decide to incorporate this dialogue, and did you remember it as you wrote, or did you move things around?

MBL: I hate writing dialogue, especially in nonfiction. I’ve seen dialogue done really well in fiction, but as a reader, I have a really hard time suspending disbelief when reading dialogue. Even in fiction, characters don’t have unique voices, and more often than not, they do. It’s a personal grudge. This is probably the most dialogue I’ve had in anything I’ve had published. Usually, I don’t even like quotation marks. I like using italics for dialogue. I find dialogue unconvincing, and writing dialogue is very, very hard for me.

This piece wanted dialogue. It felt like I’m centering this relationship, so there needed to be some dialogue, for my mom to have a voice. And I was also thinking, since the voice is a 9-year-old, I want you to take a step back with me, away from Matti as a writer who’s 30, and sit in this 9-year-old’s memory, which is why I use the present tense. One of the ways I do this is by establishing a voice via dialogue. Honestly, knowing more about dialogue and voice and character now, I would probably change some things to make the voices a little bit more unique.

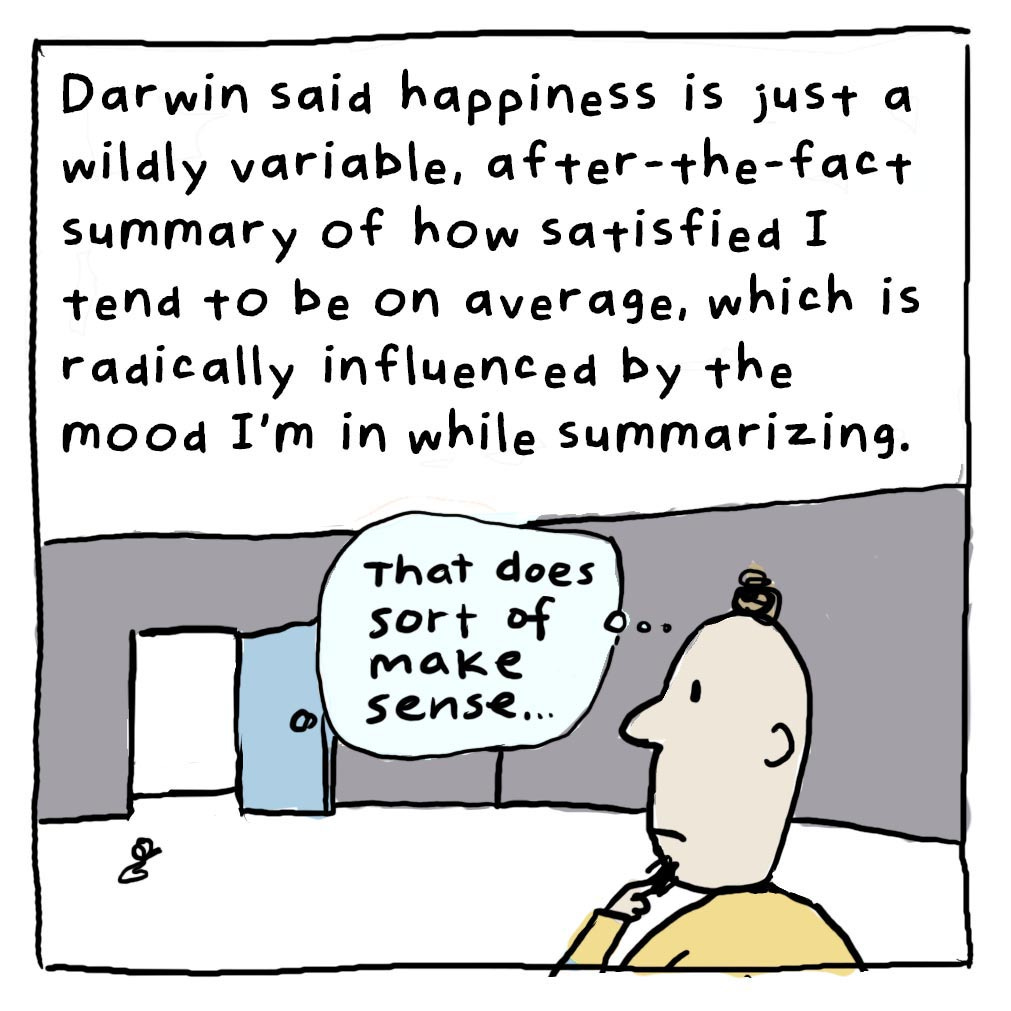

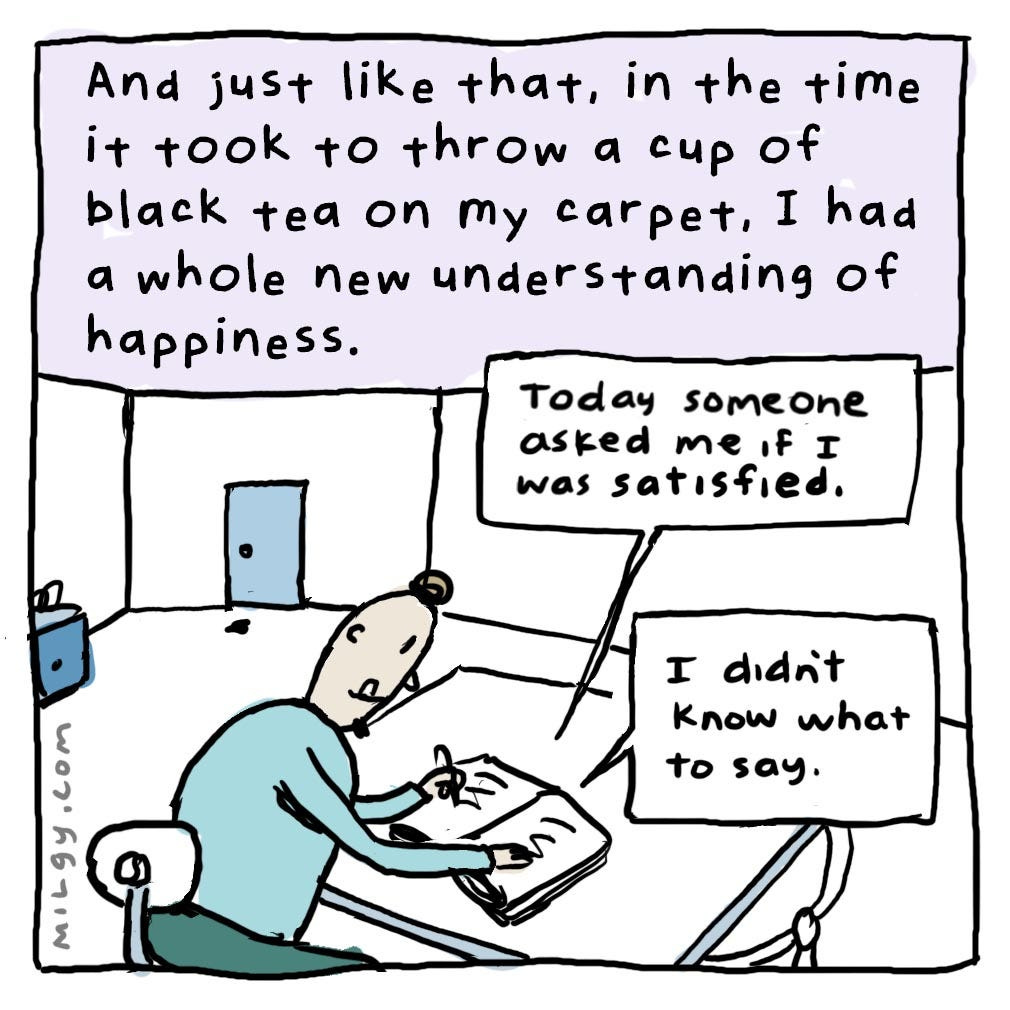

The truth is, with nonfiction, unless you’re writing about your life, there’s really no such thing as nonfiction because memory is so subjective. When I wrote this piece and sent it out, I read it to my mom and she remembers this differently than I do. She remembers some of the things that were said, where we were, what was happening, and the emotion differently. So, really, when you’re constructing dialogue in nonfiction, all of it is an approximation of the truth, and the internal question we have to ask ourselves is, “Is what I’m conveying honest?” I think we have a duty as nonfiction writers to uphold a type of emotional honesty. “Is this true to the story? Is this true to the emotion?” Rather than, “Does this dialogue map exactly what happened?”

This was 21 years ago. The dialogue is not exact, but this is how I remember it for the most part; it’s an approximation. I have that line, “I can tell you how to take a picture,” and I cut my mom off. That really captures my 9-year-old voice with my mom. Like, the me know-it-all, “I know what you’re gonna tell me,” and her saying “you’re wrong, that’s not what I’m gonna tell you, let me finish.” That feels authentic to our personalities and our voices as people, rather than, “Did every line of dialogue get said like that?”

Regina Waters is a senior at Towson University pursuing a degree in English. She currently serves as the Editor-in-Chief of Grub Street Online.