Before turning full-time to writing and then to teaching writing, I earned my living through the visual arts. Mostly I did editorial and corporate illustration, but I also sold paintings and worked as a typographer and graphic designer. Until recently, those two loves of mine—writing and visual art—had little if anything to do with each other.

But then I designed a cover for the literary journal put out by the graduate program here at the university where I teach in Georgia. This led to my designing other covers for the same journal, and to a broader interest in cover design. Soon I was designing covers for books, including some of my own. In book cover design, I discovered the perfect means to unite my two heretofore segregated passions.

One morning, I awoke with an idea, or rather a challenge. How would I design—or redesign— the covers of some of my favorite books? Starting that day, I undertook the following mission: design 20 covers for 20 famous novels in 20 days and write a little something to go with each of them. Here are [some of] the results.

To begin with, Lolita, a novel that, owing to its transgressive subject, has vexed publishers, readers, censors, and cover designers since its first appearance in print. How could one then convey the novel’s theme while respecting its literary merits? There’s even a book on the subject, Lolita, The Story of a Cover Girl: Vladimir Nabokov’s Novel in Art and Design, by John Bertram. In it, eighty renowned graphic artists take on the challenge, with results running the gamut from sublime to obscene.

Since I happen to think Nabokov’s novel is about pedophilia the way Moby Dick is about the whaling industry circa 1840, my solution errs on the side of sublimity. As I interpret it, Lolita is an embodiment of the émigré narrator’s infatuation with his newly adopted language. It’s that fresh fledgling language that Humbert Humbert has his way with across the continental USA and 300 pages.

Instead of a pair of crossed pubescent legs wearing saddle shoes or any allusion to a young girl, I chose to depict the eponymous heroine using a flowing cursive font colored with candy stripes superimposed on a sober background: half mauve (refinement), half black (mournful), with the author’s name in staid serif ALL-CAPS. The tragic collision of attracted opposites—of callow innocence and oppressive cultivation—sums up what, for me, is Lolita’s core theme.

When I first read On the Road,I was sixteen years old. I had just gotten my driver’s license. With no scarlet Corvette or Alfa Romeo Spider Veloce of my own and the Interstate off-limits, I was reduced to my father’s rusty white Pinto and local thoroughfares. Mentally, Kerouac’s novel lifted the latter restriction. Through its pages, I crisscrossed the US, experiencing all of the romance, glory, and freedom of the highway minus the nausea, boredom, and filthy restrooms. A few years later, when I read it again, On the Road so infected me with wanderlust that I dropped out of college and hit the road—not with my father’s Pinto or with an Alfa, but with my thumb. It took another five years and two and a half cross-country trips to scratch the itch planted in me by Kerouac’s second novel. It was that powerful.

By conventional standards, On the Road isn’t a very good novel. Sentimental, repetitive, and with no plot to speak of, as one early reviewer observed, it effectively takes readers on the road, “but it is a road … that leads nowhere.” Apart from Dean Moriarty (the autodidactic character Kerouac based on Neal Cassidy) the rest of the novel’s personae are thinly drawn. Its women are mainly ciphers, as is the narrator, Sal Paradise. The novel’s freewheeling prose (composed, according to legend, on a 120-foot paper scroll in three weeks, though in fact Kerouac wrote it off an earlier draft), has a hypnotic effect. But like most narcotics, it promises revelations that it doesn’t deliver.

But read unconventionally—as it was doubtlessly meant to be read—On the Road is a stunning performance. No need to take my word for it. Google “Steve Allen” and “Kerouac” and watch the YouTube video of the author reciting the end of On the Road as Allen tickles the ivories on his piano. At its best, On the Road is meant less to be read than to be sung—or not sung but wailed on a tenor sax. It’s about as close as words will ever come to improvisational jazz.

Hence my “jazzy” cover, which owes something to the original Viking hardcover, designed by Bill English featuring a small geometric abstract illustration in red, white, and blue on an austere field of pure black. For my cover, I kept the black background, which fills the negative space carved out by the title’s hand-drawn, closely-packed, primary-hued letters—jazzy bright notes in a dark smoky nightclub. If the novel’s main theme—movement for its own sake— is expressed at all, it’s by those arrow tips appended to two of the letters. If those indicators are too subtle, it’s okay with me, since as far as I’m concerned, On the Road is as much or more about jazz as it is about travel.

If you came of age around the time I did, the two great African American novels were Richard Wright’s Native Son and Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. If James Baldwin didn’t make the cut, it’s because Baldwin wasn’t at his best in the novel form. Though it had been around longer than the other two novels, as of 1975, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God had only just been rescued from critical purgatory. Richard Wright was among its harshest critics, accusing Hurston in his review for The New Masses of pandering to racist stereotypes. Alice Walker had yet to publish The Color Purple, her finest novel, and Toni Morrison was just starting to make her mark as a serious literary novelist and remained to be canonized.

It may be sheer fancy, but I suspect that back around 1975, young book lovers like me divided neatly between fans of Invisible Man and fans of Native Son, with the twain rarely meeting. For me, hands-down it was Native Son, the story of Bigger Thomas, whose fate plays out metaphorically in the novel’s first pages, wherein a rat is pursued, cornered, and crushed to death with the heel of a shoe by the novel’s protagonist who has no idea that he is his own executioner. From the rude awakening of a clock alarm going off with which it opens, to the “faint, wry, bitter smile” on Bigger’s face as the caged door of his death row cell slams shut, Native Son is wall-to-wall drama (or, as some critics had it, melodrama).

If Native Son’s M.O. is drama, Invisible Man’s target is satire. Though its theme and underlying message are serious, the story itself is anything but earnest. Except for Mark Twain, what American fiction writer has served up sassier satire than the scene in which the novel’s unnamed protagonist—employed by the Liberty Paint Factory, whose claim to fame is a superior brand of “pure” white paint (“Optic White”), the whitest in the world—learns the secret as it is revealed to him in the following exchange between him and a fellow employee tasked with showing him the ropes:

“…[P]ut in ten drops of this stuff,” he said. “Then you stir it ‘til it disappears. After it’s mixed you take this brush and paint out a sample on one of these.” He produced a number of small rectangular boards and a small brush from his jacket pocket. “You understand?”

“Yes, sir.” But when I looked into the white graduate I hesitated; the liquid inside was dead black. Was he trying to kid me?

“What’s wrong?”

“I don’t know, sir . . . I mean. Well, I don’t want to start by asking a lot of stupid questions, but do you know what’s in this graduate?”

His eyes snapped. “You damn right I know,” he said. “You just do what you’re told!”

“I just wanted to make sure, sir,” I said.

Invisible Man’s satirical nature, together with its loosely-structured, picaresque, rogue’s progress plot best explains why at fifteen the novel failed to catch fire with me. Bugs Bunny cartoons and MAD magazine notwithstanding, satire requires more sophistication than most adolescent boys can claim, and I was no exception. Invisible Man’s layered ironies were lost on me, as was its considerable wit. Still, I loved the prologue that begins, “I am an invisible man,” and goes on to describe the underground chamber in which the narrator has taken refuge from American society—a burrow festooned with hundreds of bulbs illuminated with wattage pilfered from “Monopolated Light.”

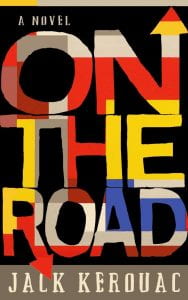

Since I’ve alluded to it, I guess now is as good a time as any to present my cover for Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston’s second and most celebrated novel. Written in 1936 when she was forty-five and published a year later, though now consistently ranked among the best English language novels, when it first appeared, Hurston’s book was poorly received. As Hurston herself notes in her autobiography Dust on the Tracks, a good part of the blame for the novel’s initial critical and commercial failure can be laid at the feet of her unwillingness to contextualize her all-black cast as victims of segregation and racism. While novels like Native Son and Invisible Man found their raison d’être in white oppression, in Hurston’s novel white people and their prejudices occupy roughly the same space as mammary glands on a bull.

At first not only was Hurston’s novel dismissed or ignored, to some measure it was condemned mostly by fellow African American authors like Richard Wright, who felt that by not directly or even obliquely confronting racism, Hurston had not only abdicated their cause, but injured it by suggesting that Jim Crow wasn’t such a big problem for black folk after all, but that they had other fish to fry. Asked why she hadn’t confronted race in her novel, Hurston replied, “Because I was writing a novel and not a treatise on sociology. … I am not interested in the race problem, but I am interested in the problems of individuals, white ones and black ones.”

Ironically, Hurston’s refusal to participate in what she called the “sobbing school of Negrohood,” to which most of her fellow Harlem Renaissance writers were committed, resulted in her and her work being marginalized by leaders of the so-called “New Negro Movement.” Her refusal to write about discrimination caused her to be discriminated against. It’s reassuring to know that Hurston lived long enough to see her novel survive most of its dutifully polemical—and duly forgotten—brethren. Politically motivated authors take note!

And though Hurston’s novel doesn’t take racial discrimination as its theme, it dramatizes another form of suppression: the objectification and subordination of women by men. Indeed, it has been argued that through the cruelties and injustices inflicted on women by men in Hurston’s novel, racial discrimination is represented by proxy with the inequities visited upon the novel’s men in the hidden white world beyond the novel’s scope imported into it in the form of domestic abuse and other strains of sexual mistreatment. If Their Eyes Were Watching God dropped the ball on racism, it scored a goal for feminism at least in the black community.

For my cover design, I had in mind two things: a wood– or linocut print of black faces (preferably women’s) and a bright earthy color scheme. The color scheme was no problem; Adobe Illustrator would supply me with all the colors I needed. The print was another matter. I set about searching online. As luck had it, I found the perfect image: a linocut of five African or African-American women, seen from the neck up and grouped tightly together. Titled “Faces á la Picasso,” it’s the work of African-American artist Margaret T. Burroughs (1917-2010).

In addition to her work as an artist, Burroughs was an educator and a prolific author of books and articles especially for black children, to help them appreciate their cultural roots while increasing their awareness of art. In the early 1950s, she founded Chicago’s Lake Meadows Art Fair. She was also co-founder of the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago, Illinois.

The print I found (whose appearance online is courtesy of the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art) was signed in 1993. It is owned by a private collector.

Published by Scribner’s in 1926, the first edition featured a Hellenistic jacket design illustrated by Cleonike Damianekes. The illustration, printed in a medley of beiges and browns, depicts a loosely-robed, exhausted-looking woman inclined against an even more tired-looking tree. Her head is resting on her shoulder, her eyes closed, both shoulders and one thigh exposed, cupping a golden apple in one hand, and a pan’s pipe resting by her sandaled foot.

What this image has to do with the plot of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, let alone with its characters (who have as much in common with classical Greece as The Three Stooges) is anyone’s guess. But Hemingway’s editor, Maxwell Perkins, felt that the illustration “breathed sex” and would therefore appeal to female readers. Whether owing to this or not, the first print run of Hemingway’s first novel—5090 copies —sold out within two months. Subsequent larger runs sold out even faster.

The plot of Hemingway’s novel can be summed up thusly: a group of expat louts travel to Spain from Paris to run with the bulls in Pamplona. Lest you take umbrage at my characterization of the novel’s dramatis personae, a recent nonfiction book by Lesley Blume that unravels the real story behind Hemingway’s novel is titled Everybody Behaves Badly.

In fact, the novel began its life as, if not a memoir, something very close to one. An early draft version of the narrator character who would become Jake Barnes was named “Hem” while other characters bore the names of their true-life counterparts. And if the final draft exemplified Papa’s “iceberg theory” (“The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water;” i.e., the less said and the more implied the better), it was largely thanks to F. Scott Fitzgerald, who, having read the draft manuscript, persuaded him to cut the other seven-eighths.

Many consider The Sun Also Rises Hemingway’s best work. Had Hemingway been half as good a novelist as he was a short story writer, that would be an even more impressive claim. Anyway, it’s a powerful novel, the sort of novel that burns its descriptions into your senses while forever changing your view of certain things. Among such descriptions is this one that finds the narrator fly fishing in Spain’s Irati river:

… I hooked another and brought him in the same way. In a little while I had six. They were all about the same size. I laid them out, side by side, all their heads pointing the same way, and looked at them. They were beautifully colored and firm and hard from the cold water. It was a hot day so I slit them all and shucked out the insides, gills and all, and tossed them over across the river. I took the trout ashore, washed them in the cold, smoothly heavy water above the dam, and then picked some ferns and packed them all in the bag, three trout on a layer of ferns, then another layer of ferns, then three more trout, and then covered them with ferns. They looked nice in the ferns, and now the bag was bulky, and I put it in the shade of the tree.

—a description so solidly organic you can shuck out its insides. And notwithstanding Gertrude Stein’s contention that “remarks are not literature,” there are quite a few formidable ones aired by Mr. Barnes, to wit: “I mistrust all frank and simple people, especially when their stories hold together”—which alone is worth the price of admission.

For my cover, I engaged the help of a compact, fiery-eyed, adamantine Andalusian artist named Pablo Picasso. Dating from 1962, the colored linocut print (full Spanish title: “Picador et Torero Attendant le Paseo de Cuadrillas”) shows a picador and a matador in their suits of lights astride a horse. Though otherwise unaltered, I enhanced the background with some vertical bands of color and a setting (or rising) sun. The image struck me as fitting in more ways than one as Hemingway and Picasso seem to have been, as it were, made for each other. Both occupied the avant garde of their disciplines, both drank a lot, and both were supreme womanizers. They were cruel SOB’s who projected themselves into the bullring: Hemingway as the matador, Picasso as the bull. Finally, the less one knows about each, the better for their art.

Should Mr. Picasso’s heirs see my cover, and should they object to my doctoring the master’s work, they may take some comfort in the fact that this cover will in all likelihood never be used. Nor have I been compensated by so much as a nickel for it, so there’s no point in suing me.

Who was Homer? Though his name appears on the cover of every edition of the second-oldest extant work of Western literature (the oldest being The Iliad, likewise attributed to him), no one really knows. The supposedly blind bard from Ionia is no less a legendary and mythic figure than Buddha or Christ, though about the latter two we know much more.

Though every college sophomore is familiar with The Odyssey’s famous prequel, few are aware that it had a sequel. Unlike its two predecessors, however, the Telegony isn’t attributed to Homer, but to the one Cinaethon of Sparta. Nor does it exist apart from a few fragments.

As to whether Homer actually wrote either or both of the first two epics, that’s the subject of a long-standing scholarly dispute with some ascribing both creations to a single author, and others holding that the poems arrived at their final forms through countless revisions and elaborations made by many contributors over decades if not centuries. For all we know, The Odyssey has as many authors as the Bible or (according to some) Shakespeare’s oeuvre, while “Homer” may be as much of a contrivance as The Monkeys.

Complicating matters further is the fact that there’s no one “Odyssey”—at least not for those of us who can’t read Homeric Greek, let alone the poetic dialect in which its over 12,000 lines of dactylic hexameter were originally transcribed. Instead we have (at last count) seventy-five English translations, in prose and verse (including one by T.E. Lawrence, aka “Lawrence of Arabia”), so your Odyssey may be unrecognizably different from mine.

For my book cover I chose a very recent translation, the first ever in English by a woman, a young British classicist named Emily Wilson. Her version of The Odyssey begins:

Tell me about a complicated man.

Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost …

Wilson’s choice of the word “complicated” is telling. In the original Greek, the word used to characterize the epic hero is πολuτροπον or polytropon, with the prefix poly meaning “many” or “multiple,” and tropon meaning “to turn” or “turned,” suggesting that Odysseus has returned from the war a “turned” or transformed man of complex character. But while other translators have used “resourceful,” “versatile,” “restless,” “ingenious,” “man of many wiles,” and “endlessly cunning” to characterize him, Wilson chose “complicated,” a word conveying cautionary praise or softened censure, thereby, by a single stroke, establishing Odysseus as an ambivalent, ambiguous hero.

For my color scheme, I chose a stark palette of blue and white, the colors (more or less) of the Greek flag, which itself conveys the sun-bleached starkness of an Augean island. The figure of Odysseus lashed to the mast of his ship I appropriated from the ancient pottery vase known as The Siren Vase, now in the British Museum. The font is called, fittingly, “Archeologicaps.”

Soon after seeing the jacket art for what would be his most famous novel (really a novella, if you want to get technical about it), F Scott Fitzerald wrote a letter to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, on August 5, 1924 beseeching: “For Christ’s sake don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me.”

The artwork in question depicts a woman’s eyes and lips floating on a cobalt blue sea that forms the night sky. The image looms over what, with its fanfare of bright colored lights, looks like Coney Island or a carnival. In place of an iris, each heavily made-up eye holds a miniature, Matisse-like reclining nude. The lips are heart-shaped, bright red, and preternaturally small according to the epoch’s concept of feminine beauty.

The illustration was the work of a commercial artist from Barcelona named Francisco Coradal-Cougat, Francis Cugat for short. Like the novel whose cover it would adorn, it was destined to be its creator’s most celebrated creation.

Though you might assume, as others have that Cugat’s illustration took its cue from the novel’s description of a pair of giant, faded-blue, bespectacled eyes peering out over the Valley of Ashes from a billboard notice promoting the ophthalmological services of a Dr. T.J. Eckleburg (which in turn are said to symbolize the eyes of God looking down in judgment on decadent American society), it is more likely the image refers to an utterance by Nick Carraway, the novel’s narrator, at the end of Chapter IV: “Unlike Gatsby and Tom Buchanan, I had no girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs [of New York City by night].”

Not everyone felt as strongly about the image as Fitzgerald. As recalled in A Moveable Feast, when Ernest Hemingway first saw the cover, he thought it was garish and better suited for “a bad science fiction novel.” This of course is the same Hemingway who, as time went by, had ever fewer nice things to say about “poor Scott”—or anyone else who had ever done him a good turn. On the other hand, Fitzgerald’s own feelings about the Cugat cover can’t necessarily be trusted either, not when you consider that the same man who wanted it for his novel also wanted to name that novel “Trimalchio in West Egg.”

Though I like Cugat’s original cover, for my own design, I took an entirely different direction, namely: yellow. Chalk it up to a case of “literary synesthesia,” but to me The Great Gatsby is, always has been, and always will be a yellow novel. That’s the color that instantly fills my mind whenever I think of it or its title: a rich warm buttery yellow.

And just what, you ask, has “yellow” got to do with the story of J. Gatsby? Well, though it’s described by the coffee shop owner Michaelis as “light green,” Gatsby’s car (which depending on which authority you appeal to, is either a Rolls Royce or a Duesenberg), the so-called “death car”—the one that, with Daisy Buchanan at the wheel, strikes and kills Myrtle Wilson—is yellow. In fact, yellow—not green, as you might expect (the color of that pulsing light on the end of Daisy’s dock) —is the most frequently occurring color in the novel. Dr. Eckleberg’s enormous spectacles are yellow, as is the “golden” necktie Gatsby wears the first time he meets Daisy at her home. At his parties, according to Nick, Gatsby plays “yellow cocktail music.” Daisy is herself described as a “golden girl.” In its golden state, yellow is, of course, also a symbol of luxury and great wealth.

I am not alone in seeing yellow when I think of Gatsby. No fewer than a half-dozen previous covers have been yellow, including one featuring a giant dollar sign, one with a string of pearls, one with a daisy (not the character: a flower), one with the front grill of a Duesenberg (or a Rolls Royce), and one depicting a man—presumably Gatsby—wearing a suit and reclining in a chair, his top half in shadow as he sleepily contemplates a half-empty (or half-full) martini glass.

For my own yellow Great Gatsby cover, I wanted to avoid overt representations of characters or objects. Just the title in an art deco font on a yellow field. My one concession to representation is a black bowtie I added at the last moment with the title occupying roughly the place where the bowtie-wearer’s head would be.

Fitting, I think, given Gatsby’s distinction as the greatest cipher ever produced by literature. A protagonist who exists—to the extent that he exists at all—primarily as the ideas that other people have about him, and that he does nothing to discourage. Hence The Great Gatsby, our great American novella, is a doughnut with Gatsby as the hole in its center.