Shanshan Qian, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Department of Management, Towson University

Nowadays, a majority of university-level programs are intended to increase entrepreneurial awareness and to prepare students for becoming aspiring entrepreneurs (Weber, 2011). It is noted that education for awareness focuses on the students who had no experience of starting a business so the purpose of this awareness-based entrepreneurship education is to enable students to develop entrepreneurial skills and to assist them in choosing a suitable career (Liñán, 2004). The objective of this paper is to offer suggestions and insights on entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions by building on this awareness-based entrepreneurship education that is designed for the students who had not already decided which career to pursue (e.g., employment versus entrepreneurship) or who had not experienced starting their own businesses prior to enrolling in entrepreneurship courses. Entrepreneurial intentions refer to one’s desire to own one’s own business (Crant, 1996) or to start a business (Krueger, Reilly, & Carsrud, 2000).

Entrepreneurship education consists of “any pedagogical [program] or process of education for entrepreneurial attitudes and skills” (Fayolle, Gailly, & Lassas-Clerc, 2006, p. 702). The types of entrepreneurship education vary across specific target audience (Liñán, 2004).Entrepreneurial intention is a robust predictor of entrepreneurial behaviors, which has been supported by a series of social-psychological studies that assume the intention is the single best predictor of actual behavior (Bagozzi, Baumgartner, & Yi, 1989).

Regarding the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions, human capital theory (Becker, 1975) and entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Miao, Qian, & Ma, 2017) are the two theories/lenses that suggest a positive relationship between them.

Entrepreneurship education, as one category under human capital accumulation investments, should cultivate students’ attitudes and intentions toward entrepreneurship and thus prepare them for new venture creation (Liñán, 2008). Second, entrepreneurship education influences one’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy through which individuals’ entrepreneurial intentions may be enhanced (Wilson, Kickul, & Marlino, 2007).; hence, it is known as a factor that affects one’s entrepreneurial intentions (Segal, Schoenfeld, & Borgia, 2007). Further, entrepreneurship education could augment entrepreneurial self-efficacy via exposing individuals to examples of successful business planning or proactive interaction with successful practitioners (Honig, 2004).

Major Findings in Bae, Qian, Miao, and Fiet’s (2014) Meta-Analytic Review

In my coauthored paper “The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review” published in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, we tested a series of important research hypotheses related to entrepreneurship education, such as the effect of duration and specificity of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention, and cross-cultural differences in entrepreneurship education – entrepreneurial intention relationship.

Specifically, my coauthors and I found that educational format of entrepreneurship education (e.g., semester format versus workshop format or business planning versus venture creation) did not condition the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. Nor did students’ personal characteristics (e.g., entrepreneurial family background) condition the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention.

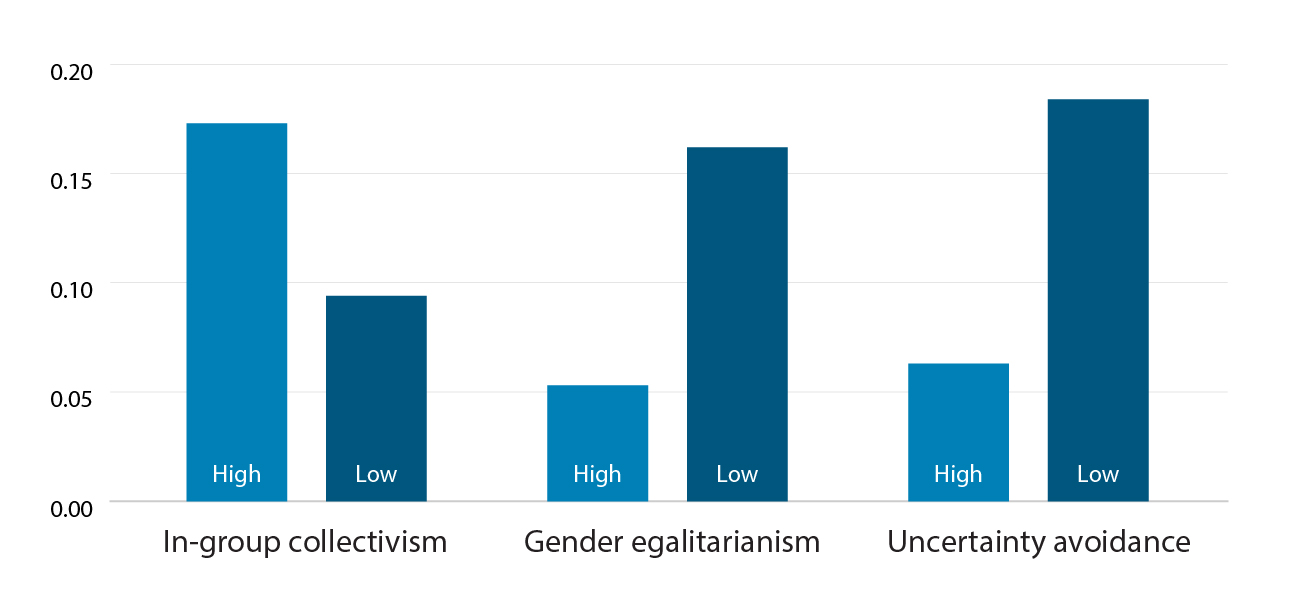

Regarding cultural contexts, the positive relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions is stronger in (1) high in-group collectivistic countries, (2) low gender egalitarianism countries, and (3) low uncertainty avoidance countries (Figure 1). In-group collectivism refers to “the degree to which individuals express pride, loyalty, and cohesiveness in their organizations or families” (House et al., 2004, p.12). Gender egalitarianism is the “degree to which an organization or a society minimizes gender role differences while promoting gender equality” (House et al., 2004, p.12). Uncertainty avoidance is “the extent to which the members of an organization or a society strive to avoid uncertainty by relying on established social norms, rituals, and bureaucratic practices” (House et al., 2004, p.11).

Figure 1. A cross-cultural comparison of the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions

Entrepreneurship Education at Towson University: An Example of Application of Research Findings

Department of Management in College of Business and Economics at Towson University sets a great example in preparing students for being future successful entrepreneurs. After receiving training in a variety of courses, students will obtain critical skills that allow them to successfully start their own businesses and will develop entrepreneurial spirits which help them effectively work in small businesses or family businesses.

With respect to course design, Department of Management offers entrepreneurship major (targeting toward business students) and entrepreneurship minor (targeting toward non-business major students). Entrepreneurship minor program was recently established and this program provides entrepreneurship skill development programs to students who are from non-business majors. This program offering coincides with my research findings that non-business students are very willing to take entrepreneurship education because they are keen on understanding the methods to integrate their major background and knowledge with entrepreneurship.

Schools nowadays offer entrepreneurship education in either semester or workshop format. The main difference between these two program offerings is the absorption time between class meetings. Programs of semester format can help students remember and retain new materials and positively influence students’ learning (Cepeda et al., 2006). Entrepreneurship programs of semester length are usually comprised of both theory training and practice training for students. For instance, these programs prepare students for learning foundational knowledge in entrepreneurship which covers idea development, entrepreneurship and society, family business and so forth. More importantly, students can learn real-world entrepreneurship cases, attend business plan competitions, and do internships from semester-length entrepreneurship programs. These programs are effective in developing students’ knowledge and skills related to entrepreneurial tasks.

Relative to semester-length programs, workshops have also provided great benefits to students. In addition to semester-length courses, entrepreneurship minor program at Towson University launched a series of activities and events on campus opening to all students and the public. For example, innovation calisthenics which operate under workshop format have ten weeks long training sessions and last for 90 minutes once a week for each training session. These programs cover topics including sounding board, design thinking, business model, and pitch practices. Students participate in hands-on practices with mentors. They also learn about idea development from the initial stage. The schedule and training of innovation calisthenics are integrated with entrepreneurship competitions at Towson University. This way of training, named as learning-by-doing that was mentioned by Minniti and Bygrave (2001), consists of “repetition and experimentation that increases [an] entrepreneur’s confidence in certain actions and improves the content of his stock of knowledge” (p. 7).

Entrepreneurship competition, an important feature of the entrepreneurship program at Towson University, allows students to present business ideas to the public and to gain awards according to judges’ evaluation. The competitions include three sub-competitions, including Big Idea Poster Competition, Tiger Cage Pitch competition, and Business Model competition. Students take steps and compete to gain access to next stage and its corresponding awards. These entrepreneurial opportunities help students nurture their initial ideas into mature ideas and actionable plans and stimulate students’ entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors.

Towson University sincerely cares about minority and entrepreneurship program in Towson University clearly reflects it. For example, entrepreneurship program in Towson University cares about female students and entrepreneurs and hosted Entrepreneurship Unplugged by inviting both male and female entrepreneurs as speakers. It is noteworthy that in Fall 2017, entrepreneurship program hosted Women+Minority Entrepreneurship Conference by inviting Dr. Leola Henry who is from R&D at McCormick & Company.

Suggestions for the Future Entrepreneurship Education

As Towson University is expanding and is home to nearly 500 international students from over 80 countries, I provide a few suggestions regarding entrepreneurship education in a culturally diverse academic environment in accordance with my research findings.

First, students who come from high in-group collectivistic cultures are more likely to exhibit consensus with their peers in their cohort because they are inclined to conform to social norms and to maintain harmony with others in their cohort (Singelis, 1994). If they work in teams, they are more likely to be followers due to their propensity to develop a high sense of team connectedness. As educators design team projects related to entrepreneurship, they may consider students’ cultural backgrounds when assigning students into groups.

Second, individuals from countries where gender egalitarianism is low are prone to relate entrepreneurship with socially constructed gender differences. Hence, educators need to mitigate students’ perception of gender inequality when delivering entrepreneurship education. Doing so should have profound beneficial effects on students who are from low gender egalitarianism countries.

Third, students may be less interested in entrepreneurship when they realize the uncertainties associated with entrepreneurship. This phenomenon may be more prevalent in high uncertainty avoidance countries. One of the proven effective approaches is to provide students with training, mentorship, and practice in order to mitigate students’ fear of failure.

Finally, my research significantly contributed to the entrepreneurship education field with respect to the finding that pre-education entrepreneurial intentions explained a majority of variance in students’ post-education entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, if the goal is to enhance students’ entrepreneurial intentions, educators should be advised to implement enrollment screening processes to select the students who already have had high entrepreneurial intentions.

References

Bae, T. J., Qian, S., & Miao, C., Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217-254.

Bagozzi, R.P., Baumgartner, J., & Yi, Y. (1989). An investigation into the role of intentions as mediators of the attitude-behavior relationship. Journal of Economic Psychology, 10(1), 35–62.

Cepeda, N.J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J.T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354–380.

Crant, J.M. (1996). The proactive personality scale as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(3), 42–49.

Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., & Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006b). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: A new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(9), 701–720.

House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Leadership, culture, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., & Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411–432.

Liñán, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccola Impresa/Small Business, 3, 11–35.

Liñán, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 257–272.

Miao, C., Qian, S., Ma, D. (2017). The relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and firm performance: A meta-analysis of main and moderator effects. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(1), 87-107.

Minniti, M. & Bygrave, W. (2001). A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(3), 5–16.

Segal, G., Schoenfeld, J., & Borgia, D. (2007). Using social cognitive career theory to enhance students’ entrepreneurial interests and goals. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 13, 69–73.

Singelis, T. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580–591.

Weber, R. (2011). Evaluating entrepreneurship education. Munich: Springer.

Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406.