Natalie M. Scala

Associate Professor, Department of Business Analytics & Technology Management, Towson University

Josh Dehlinger

Professor, Department of Computer and Information Sciences, Towson University

Lorraine Black

Graduate Student in Supply Chain Management, Towson University

Saraubi Harrison

Solutions Architect, Amazon Web Services

Katerine Delgado Licona

Juvenile and Economic Crimes Unit, Baltimore County State’s Attorney’s Office

Aikaterini Ieromonahos

Major in Law & the American Civilization, Towson University

Introduction and Motivation

The use of electronic voting equipment in the United States’ elections has been commonplace since the early 2000s, with the idea first introduced by the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (US EAC, 2018). The introduction of electronic voting equipment was, in part, a response to the punch-cards controversy in the 2000 Presidential Election and the subsequent Bush v. Gore court proceedings. The cybersecurity issues related to electronic equipment became of widespread concern during the 2016 Presidential Election, with a report and congressional testimony by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III confirming that the Russian Federation took sweeping and systematic actions, in violation of United States criminal law, to interfere in the election (Helderman and Zapotosky, 2019; Mueller, 2019). Although evidence does not point to equipment and voter records actually being compromised, the Department of Homeland Security revealed that 21 states, including Maryland, were subject to cybersecurity attacks on their voting registration files or public election sites by the Russian Federation (Horwitz, Nakashima, and Gold, 2017). The Senate Intelligence Committee also concluded that election systems in all 50 states were targeted by Russia in 2016 (Sanger and Edmonson, 2019).

Our ongoing, funded, and student-centered research takes a unique systems approach to elections security and specifically considers potential cyber, physical, and insider threats to an election. Cyber threats can exist regardless of an active Internet connection; physical threats involve tampering with equipment; and insider threats stem from human interactions with the process (Price, et al., 2019). This approach distinguishes our research from existing literature, which generally focuses only on cyber threats. We further differentiate from existing research by focusing on local polling places; most existing research is at the state level. We consider varied sources of threat and consider polling places, because those places are where the public actually interacts with the voting process. The experience the public has at a polling place drives overall confidence in voting integrity. For example, if voters have positive experiences at a polling place, they may feel confident in the voting system. However, if the polling place was disorganized or equipment malfunctioned in front of voters, for example, they may not feel confident their votes were accurately recorded. Thus, it is crucial that not only are the actual security and integrity of votes maintained during early voting and on Election Day, but also the public has a positive and affirming experience at the polls.

Our research takes a “see something, say something” approach and develops training modules for Election Judges to identify and respond to potential cyber, physical, and insider threats that may emerge during early voting and on Election Day. The training empowers Election Judges to mitigate emerging security issues or elevate them for proper assistance. Security issues that may emerge at a polling place must be immediately remedied, as elections cannot be redone or rescheduled. An election has one chance to correctly and securely record votes; the confidence in, and health of, our democracy depends on election integrity.

Threats and the Maryland Process

We partnered with the Harford County Board of Elections in Maryland to develop training modules. All counties in Maryland employ the same process and use the same equipment during early voting and on Election Day, and polling places are arranged into the following general sections or stations: check-in, voting booths, scanning unit, provisional voting, and disabled access. Maryland uses a paper ballot on which voters indicate their choice by filling in bubbles with pen marks; those ballots are then counted at the polling place using an optical scanner. The ballots are then retained in bins under the scanner as a paper trail. Various Election Judges are assigned to each station, and a Chief Election Judge oversees the entire polling location. Threats may emerge at any station at a polling place. Threats may evolve from accidents or honest mistakes made by voters and/or Election Judges, or threats may emerge from those interacting with the process with malicious intent. The developed modules train Election Judges to recognize that a threat may be present and equips them with the actions to take to mitigate the threat. The modules also review proper equipment usage, in an effort to avoid an Election Judge inadvertently becoming an insider threat through honest mistakes and improper use of equipment. Examples of threats that may occur at a polling place are outlined in Price, et al. (2019); that paper identifies 25 potential vulnerabilities to the Maryland election process, even though no evidence exists that those vulnerabilities were previously compromised in an election. Other related sources of risk in elections security, categorized into cyber, physical, and insider threats, are discussed in Locraft, et al. (2019).

Design of Modules

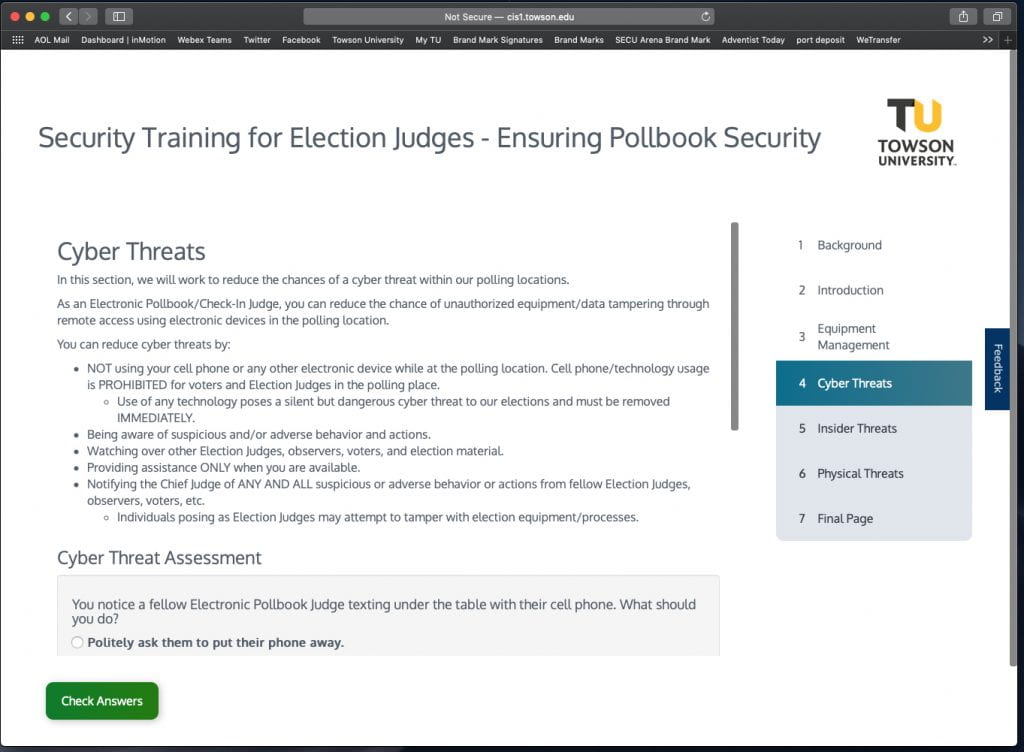

We created a training module for each of the five general stations at a Maryland polling place. Specifically, the modules created are for electronic pollbooks, voting booths, the scanning unit, provisional voting, and ballot marking devices. Electronic pollbooks are digital records of all registered voters and are used to verify voters at the check-in station. Voters mark their paper ballots in voting booths. The scanning unit reads the marked bubbles on ballots and records votes. Provisional voting is reserved for voters whose registration cannot be confirmed at the check-in station. Ballot marking devices are primarily used to assist disabled voters with marking their choices on their ballots, although all voters are welcome to use the marking device. We also created a module for Chief Judges, as they have unique responsibilities to oversee and manage the entire polling location. Each module has four main training sections: equipment use, cyber threats, physical threats, and insider threats. Self-assessment questions are at the end of each section, and a user must correctly answer each question to move on to the next section. Users receive a Certificate of Completion upon completion of the entire module. As an example of module design, Figure 1 provides a screenshot from the cyber threats section of the electronic pollbooks module.

As noted in Price, et al. (2019), a cyber threat may be related to phones used on-site containing existing malware or other cyber-related concerns. Thus, the electronic pollbooks module addresses that threat by instructing Election Judges not to use their cell phones or any other electronic device while at the polling location. Similar approaches are taken in all modules for each type of threat. Furthermore, the equipment section identifies proper handling and use of equipment before, during, and after the polling place is open. Considering threats over time (before, during, and after) supports other research we have in development that takes a Markov chain approach to assess overall threat and risk (Price, et al., 2019; Locraft, et al. 2019). Educating Election Judges on equipment use should help to mitigate against threats that may emerge from mistakes and improper handling. Equipment use may also address more nuanced threats, such as a lack of synchronization between multiple pollbooks that, if persisting, may indicate malfunctioning or compromised equipment.

Election Judges are our first line of defense to the security of our elections. Our training modules instill self-efficacy in Election Judges and Chief Judges regarding identifying and mitigating cybersecurity threats.

Module Deployment

To deploy our modules, we use the established Security Injections@Towson e-learning system (Taylor & Kaza, 2011). The Security Injections@Towson project has developed an ecosystem of over 50 teaching/training modules that introduce cybersecurity in computing classes; each module is packaged and hosted within the system. Our library of training modules, along with a supportive ecosystem of materials and resources for election officials will be housed on the project website. The Security Injections@Towson project is increasingly recognized as a model for introducing secure coding in lower-level programming classes. As of 2019, over 360 faculty, across 221 institutions, including 91+ community colleges and several high schools, have completed more than 3,100 cybersecurity modules (Cyber4All, 2019). We anticipate similar accessibility and opportunity for use by counties and Election Judges pertaining to our training modules.

Goals and Conclusions

The goal of these training modules is to empower Election Judges to identify and mitigate threats that may emerge at a polling place during early voting or on Election Day. Harford County Election Judges participate in in-person training in the months leading up to an election. However, the in-person training currently does not include training on cyber, physical, and insider threats outside of active shooters. Therefore, we advise that the online modules to be administered two to three weeks prior to Election Day or Early Voting so that Election Judges can have a refresher on how to use the equipment as well as an opportunity to gain knowledge on identifying and mitigating potential threats. In some Maryland jurisdictions, such as Baltimore City and Prince Georges’ County, hiring Election Judges on the day of the election is not uncommon. In those cases, a poll worker has no previous training before having access to and interacting with the process. As a result, we advise day-of hires to interact with the module before beginning their work. In that scenario, an Election Judge can have a basic introduction to equipment use along with the crucial cyber, physical, and insider threat awareness training.

Election Judges are our first line of defense to the security of our elections. Our training modules instill self-efficacy in Election Judges and Chief Judges regarding identifying and mitigating cybersecurity threats. Knowing that Election Judges are equipped to address threats if they occur at a polling place and that they clearly know how to handle the voting equipment should increase the public’s confidence in and improve their experience at polling places. Managing cyber, physical, and insider threats enable the integrity of votes to be maintained throughout the entire process.

We are currently conducting a follow-up study to assess the degree to which Election Judges learn about equipment use and cyber, physical, and insider threats from interacting with the training modules. The study employs pre- and post-tests to assess learning. Preliminary results show, with statistical significance, that Election Judges do learn and become aware of threats and mitigations while interacting with the modules.

These modules will be used by Harford County during the 2020 Presidential Election cycle. We encourage all Maryland counties and cities to adopt these modules as part of their poll worker training. Together, we can ensure the security of our elections.

Acknowledgments

Towson University’s School of Emerging Technologies and the BTU Initiative partially funded this research and module creation. The authors would especially like to thank the Office of Civic Engagement and Social Responsibility at Towson University for their support of the follow-on learning assessment study. The authors would also like to thank Cynthia Remmey and the Harford County Board of Elections team for their ongoing support of and engagement in this research.

References

Cyber4All. (2019). Security Injections Home. Retrieved from https://cis1.towson.edu/~cyber4all/index.php/security-injections_home/

Helderman, R. S., & Zapotosky, M. (2019). The Mueller report: Presented with related materials by The Washington Post. New York: Scribner.

Horwitz, S., Nakashima, E., & Gold, M. (2017, September 22). DHS tells states about Russian hacking in 2016 election. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/HorwitzEtAl

Locraft, H., Gajendiran, P., Price, M., Scala, N. M., & Goethals, P. L. (2019). Sources of risk in elections security. Proceedings of the 2019 IISE Annual Conference. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/LocraftEtAl2019

Mueller III, R. S. (2019). Former Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election. U.S. House of Representatives Committee Repository, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IG/IG00/20190724/109808/HHRG-116-IG00-Transcript-20190724.pdf

Price, M., Scala, N. M., & Goethals, P. L. (2019). Protecting Maryland’s voting processes. Baltimore Business Review: A Maryland Journal. Retrieved from https://www.cfasociety.org/baltimore/Documents/BBR_2019%20Final.pdf#page=38

Sanger, D. & Edmonson, C. (2019, July 25). Russia targeted election systems in all 50 states, report finds. The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/25/us/politics/russian-hacking-elections.html

Taylor, B., & Kaza, S. (2011, June). Security injections: modules to help students remember, understand, and apply secure coding techniques. In Proceedings of the 16th annual joint conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education

(pp. 3-7). ACM

United States Election Assistance Commission. (2018). Help America Vote Act. Retrieved from https://www.eac.gov/about/help-america-vote-act/