A year after his arrival at the State Teachers College at Towson but before founding the theater program on campus, Dr. Dick Gillespie started a new student group.

“A debating society is being formed this year,” reported the September 28, 1962 Towerlight. It “will be open to all students regardless of experience as an extracurricular activity.” By the time the story came out, a practice debate had already been scheduled with Morgan State College.

From the start, Gillespie envisioned the group would enter and host tournaments. And within the first year, students were already besting more experienced teams on topics such as “Resolved: That the Non-Communist Nations of the World Should Establish an Economic Community” and “Resolved: Federal Government Should Guarantee Higher Education for All Qualified High School Students”.

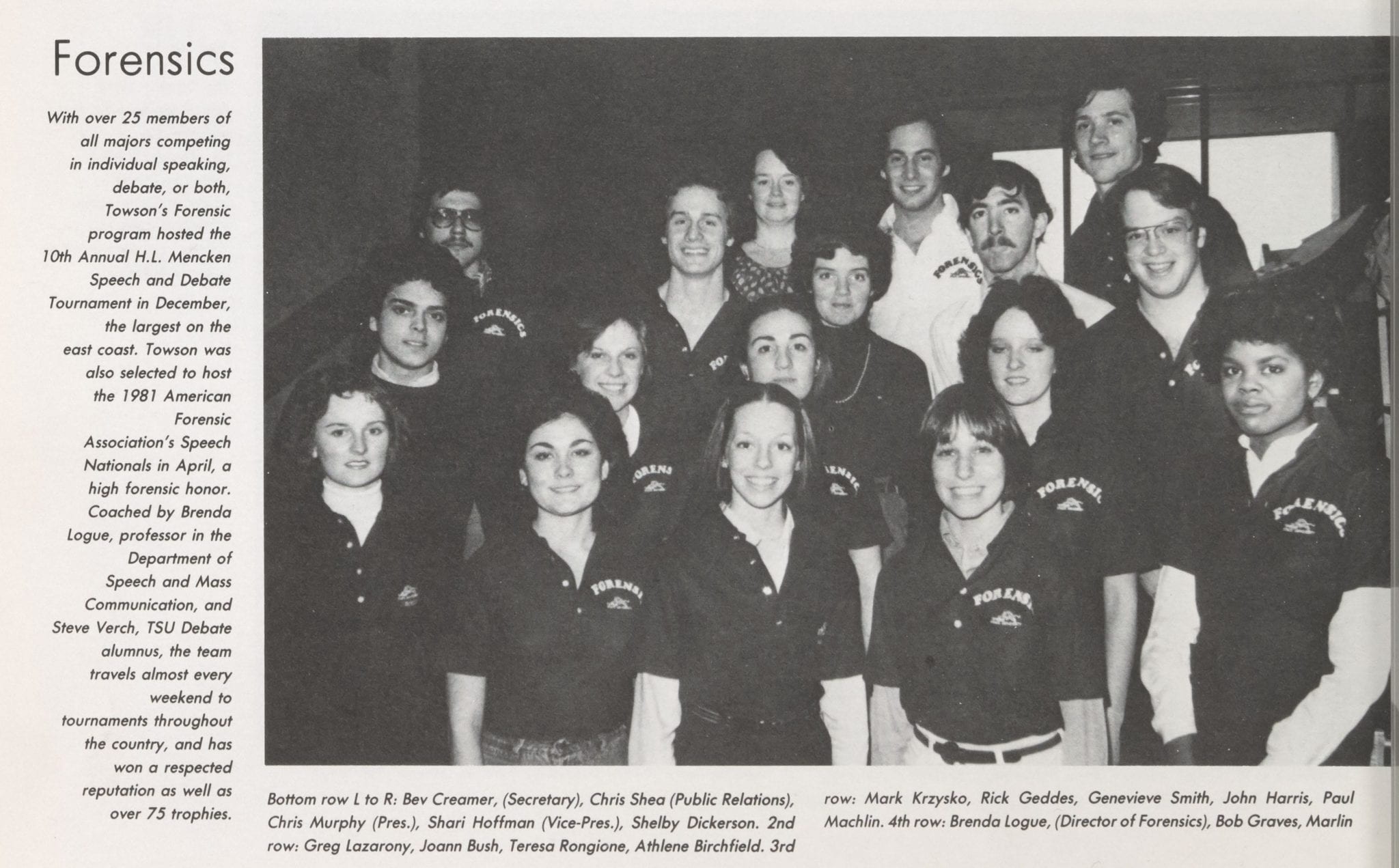

By 1970, long-time coach Brenda Taylor, later Logue, was in place, and the focus of the Debate Council was shifting. The school began hosting the H.L. Mencken Memorial Forensic Tournament which was sponsored by the Baltimore Sunpapers and would remain a fixture on Towson’s campus for about 15 years.

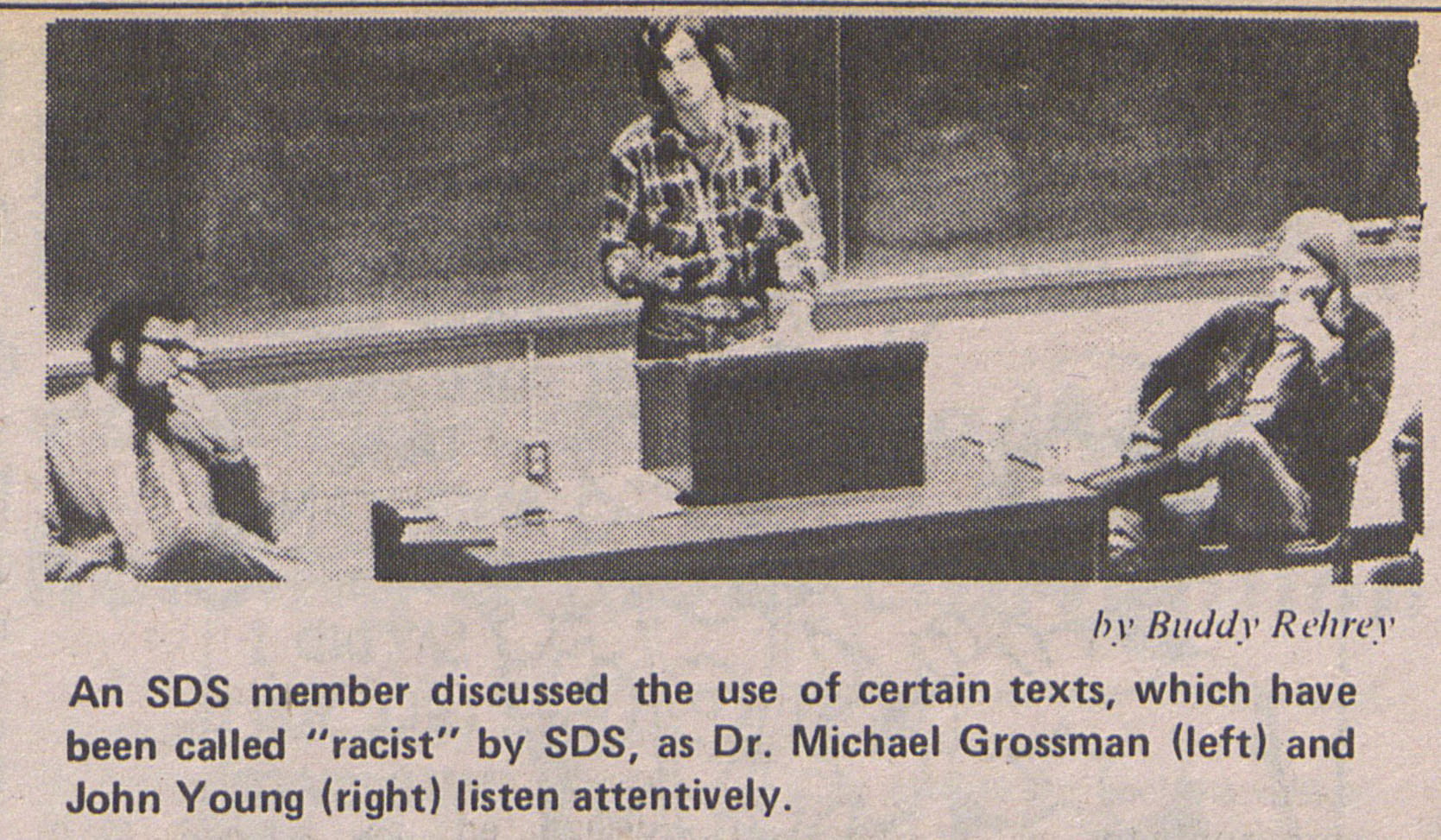

Besides traveling to and hosting debate tournaments, the group also worked with other student organizations on campus to sponsor broader discussions. In 1972, for example, the Debate Council worked with Towson members of Students for a Democratic Society to discuss charges of racism about a book used in a Political Science seminar.

1972 also saw a change in the name of the group, from Debate Council to Forensic Union and was “comprised of the old Debate Council, the discussion teams, and individual events competitors.” As Logue told the Towerlight, “the group was formed to provide involvement in all types of speaking rather than just inter-college debate.”

A March 1981 Towerlight article pinpoints the differences between speakers and debaters:

“The speakers participate in more individual events, where they present informative, persuasive, impromptu or extemporaneous speeches . . . . ‘Speakers need the ability to share information in a comprehensible way,” says Logue. “In persuasive speaking particularly, you need the ability to emotionally and logically convey the information.”

The article goes on to quote Leonard Gutkoska, a member of the debate team. “For debate, you need someone who can think on his feet, is willing to work hard and is able to persuade others to buy his arguments.”

Both speakers and debaters devoted countless hours to research and analysis in order to shore up their points. There were more speakers on the team than debaters, perhaps because, as Logue said “It’s harder to be a debater because you either win or lose, where in speech you are ranked.”

All in all, though, there was agreement that the team worked to support and encourage one another, no matter whether they were speakers or debaters.

In the fall of 1984, the Forensic Team began a column in the Towerlight called “Forensics footnotes”. The idea was to write presentations and speeches that showcased how the team responded to issues used by the Cross Examination Debate Association with that hope that the columns would bring more notice to a team that continued to do well in tournaments, but was not as well-known on campus.

In 1994, Dr. Ken Broda-Bahm became the new Director of Forensics, and within three years, the team was ranked as 8th in the country. And while that was exciting for the team, the lack of recognition by outside constituents meant that funding the team was always a struggle.

Perhaps things would have continued in the same vein — stellar performances by individual students at tournaments and competitions but little recognition from their peers — but in 2008, Deven Cooper and Dayvon Love made the rest of campus take notice.

Cooper and Love both grew up in Baltimore and participated in the Baltimore Urban Debate League. For them, BUDL was a way to do something positive and meaningful, and it gave them the experience to use their own stories as arguments within the debate setting.

As Cooper said in March 2008 Towerlight article, “Unfortunately, Dayvon and I can’t see it as a game all the time because you’re talking about peoples’ lives probably close to us, or have the same historical background as us.” They used this viewpoint to challenge traditional ideas of how one should or should not debate.

In the CEDA national tournament that May, the Towerlight reports that Cooper and Love “deviated from the typical debate style of quoting well-known scholars and politicians, and instead, incorporated the use of hip-hop in questioning the structure of the debate community. Love and Cooper compared the sport of debate to a form of supremacy.”

“‘We think that debate in general relies on traditional academic qualifications to make arguments,’ Love said. ‘We pulled out particular practices in the debate community that bolster white supremacy.'”

Cooper and Love won that tournament, becoming not just the first Towson students to do so, but also the first all-black team to win the CEDA national tournament.

As Cooper and Love continued to debate for Towson, other black students joined the team, like Adam Jackson, Deverick Murray, and Ignacio Evans. And like the members of the Debate Council from years past, they worked together not just to win debates, but to make Towson University a better place for all its students.

Murray was president of the Black Student Union, an organization that has been on campus since 1970, from 2008-2010. During his time as president, he helped organize the Ebony Lounge, and other student focused events. He advocated for the creation of a Black Studies Department on campus. He also helped bring different campus diversity clubs together to discuss how they could overcome small divisions in favor of creating a more unified message.

Evans, another alum of BUDL, was featured in a Washington Post story in 2007. At Towson, he was also the Vice President of BSU.

Jackson was part of the Commuter Activities Board. He became President of a new student group on campus, Brotherhood: Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, which was founded in 2007. He wrote letters to the editor of the Towerlight, bringing attention to racial stereotyping by its contributors. He confronted the SGA about what he saw as willful ignorance about racist attitudes on campus. By 2010 he was writing columns for the Towerlight which focused on the experience of students of color on Towson’s campus.

In November of 2009 multiple student groups, including the Brotherhood and BSU, rallied to commemorate the forty years since the Black Student Union marched on the Administration in 1970, demanding equal treatment.

In 2010, Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle moved from a Towson campus student organization to a Baltimore community organization.

Three of the founders, Love, Murray, and Jackson, are TU alumni. And while they’ve moved off campus, they still advocate for students at Towson.

In 2013, LBS and Debate Team members brought forth allegations that the coach for the Forensics Team was abusive to members of the team. There were also concerns that due to cost issues, the team could not travel for debate tournaments, and members created a GoFundMe to raise money for travel. While the University brought in an outside party to investigate the charges, the coach was removed and the team was allowed to travel to specific tournaments.

With new coaches in place, including Debate Team alum, Ignacio Evans, two members of the Towson University Forensics team once again won the CEDA National Debate Championship, and this time, Ameena Ruffin and Korey Johnson were the first all-black women’s team to do so.

In November of 2015, black students again marched on Towson’s administration offices, and presented a list of thirteen demands to then Interim President, Timothy Chandler. One of the demands from the #OccupyTowson group was a restoration of funds to the TU Debate Team.

By 2016, the team was back on the road.

While Ignacio Evans continues to coach Towson University’s Debate Team, his former teammates continue to grow LBS. The organization hosts events to support and promote businesses owned by black people, advocates for local and state legislation to help black communities, and creates events for the celebration of black culture.

In February of 2018, the organization received a $10,000 donation from J. Cole.

Through its fifty-five year history, debate at Towson has been synonymous with making campus a better place.

And Towson University’s Debate Team alumni show in very real ways how they’re taking that vision out into the world.