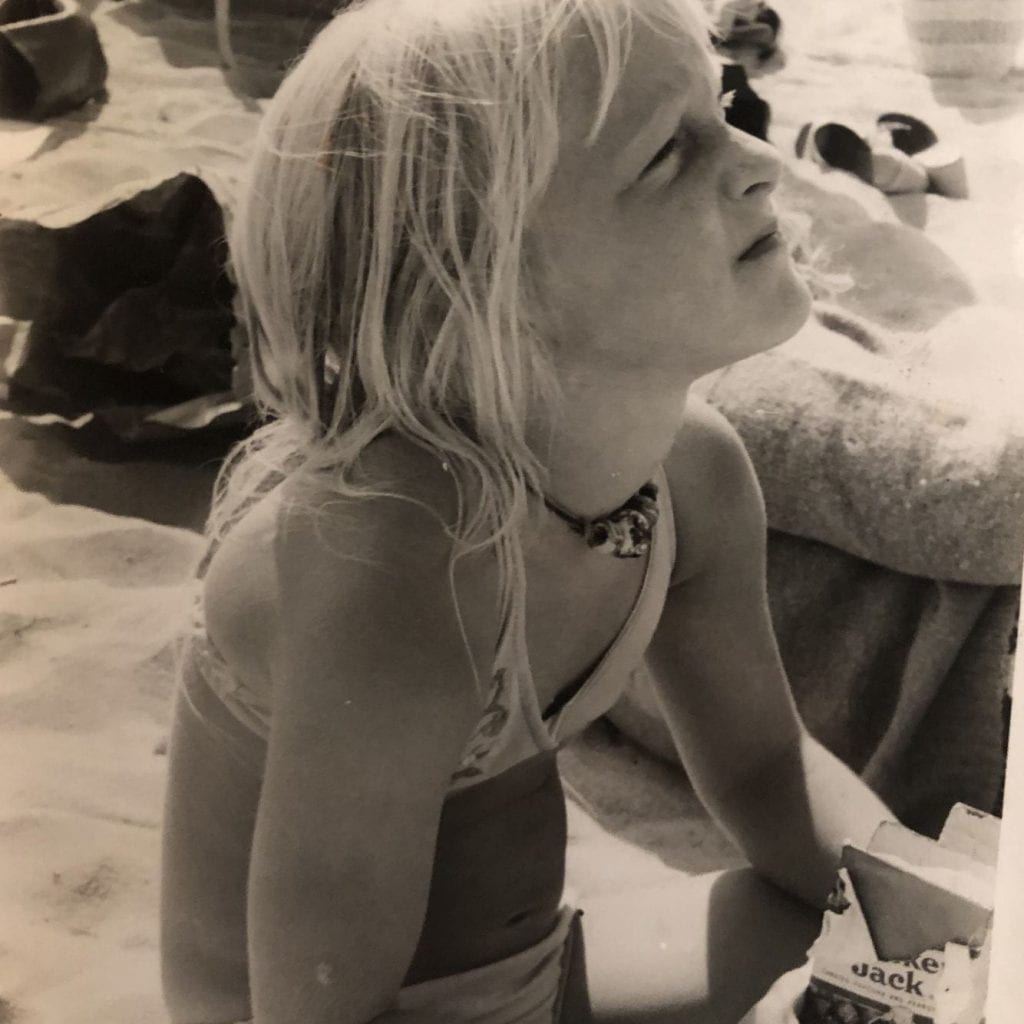

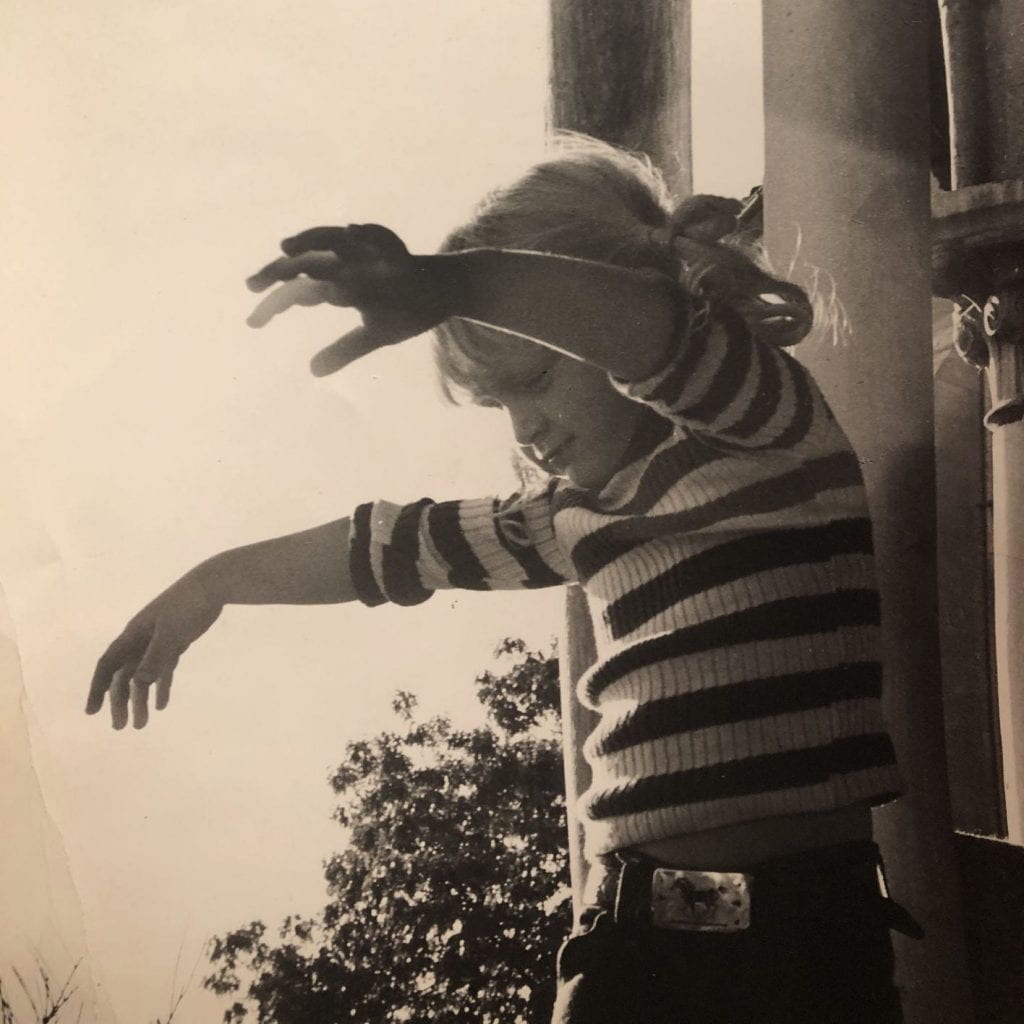

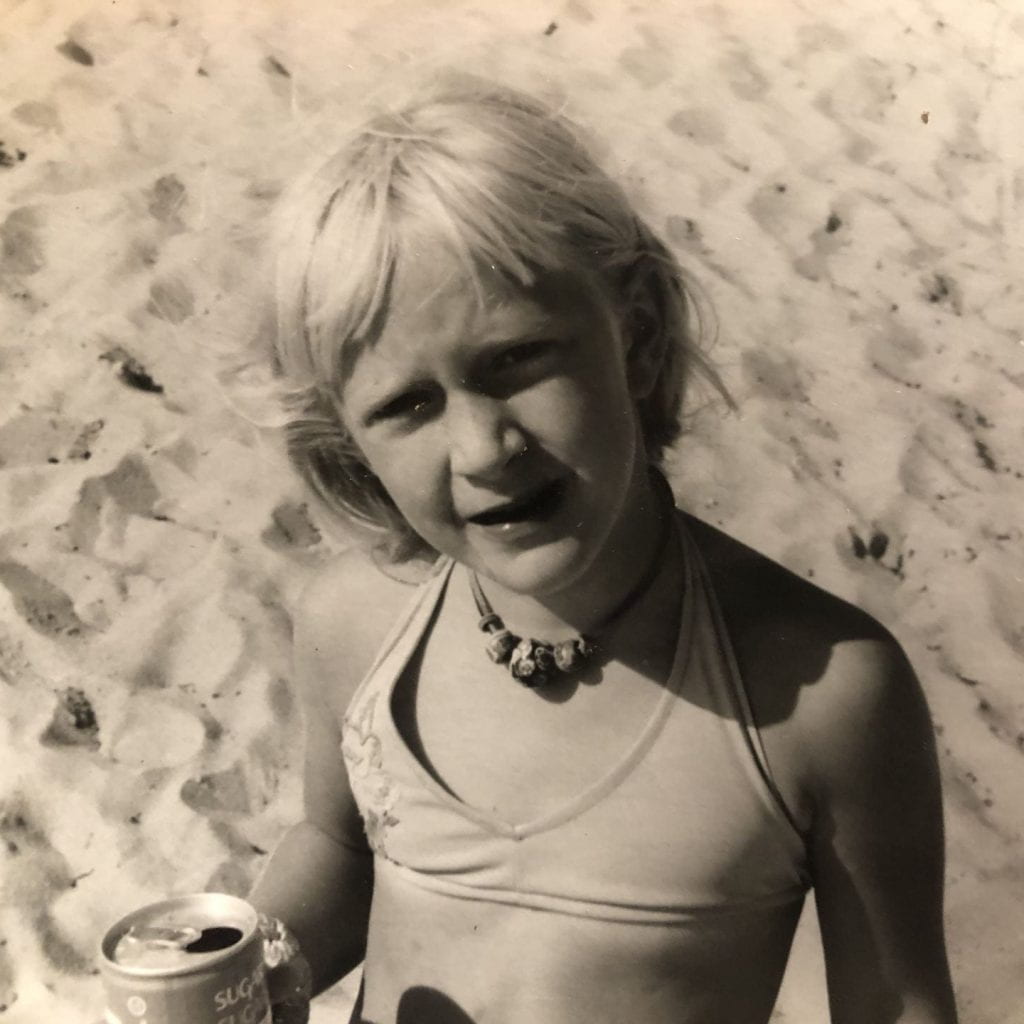

By Tavia LaFollette (pictured)

GHOSTS

When I was around five years old, we lived on East 91st Street in upper Manhattan. It was the 1970s, an era of bell-bottoms, tapestries, skateboards, and polyester. I could smell all of these things when I would hide in my parents’ closet, usually behind Ophelia. Ophelia was the name of our vase-shaped wicker laundry basket. It was not odd to me that our laundry basket was named Ophelia. That was how it was identified to me. I had no idea who “Ophelia” was in literature and art… or the symbolism behind stuffing her with dirty laundry. I am not sure I even knew what a laundry basket was, just that Ophelia got all our soiled clothes.

As I sat with my legs between the bedposts, clutching the brazen brass railing for strength, I would smell the strong cool odor of my parents’ brass bed. This is how I iced my screams of discontent while my mother would try to tear through my straggly blonde hair.

“Oh, stop acting like a Jap.” My mother snapped one morning, we were late and I was not helping the situation.

I distinctly remember thinking this thought, but didn’t dare give it a voice at the time:

Why was my mother calling me Japanese? Do they tend to get terrible tangles too?

How does a kid, growing up in New York City, in a family of artists and activists who fought to change the world during both the civil rights and the peace movement, have a vocabulary with ethnic slurs like “Japs”? These slurs, post-World War II, insults referred to the Japanese and “J.A.P.,” a Jewish American Princess. I was confused.

When the pandemic first put us on lockdown, I was haunted by the people before me. If quiet enough, you can listen to the land which still breathes the indigenous civilizations, metropolises of knowledge that were disintegrated by similar diseases—transported through handshakes. And if not fragmented and spread by the wind via plague—than by slavery and forced assimilation.

These Knowledge Keepers are still here. Can we as a country, learn to listen?

My father’s family came to NYC when New York was still New Amsterdam and my mother’s side traces back to the Mayflower. Through my family tree, I can connect at least three 10th great-grandfathers that fought in the Pometacomet’s Rebellion (First Indian War/King Philip’s War). Zabriskie Point is named after another one of my relatives who desecrated the sacred desert, turning ritual into a lucrative scrubbing agent to the pots and pans on wagon trains. As the vice-president, he helped to produce BORAX and the “20 mule team” that moved the scared sand out of Death Valley. My grandfather was part of a special regiment charged with experimenting how biplanes could be used in war and he chased Poncho Villa up and down the Mexican border.

I am the settler. I am the colonizer. But wait, this is meant to be a piece about silver linings!

Okay, during this pandemic, I found myself grateful. Grateful for the first time that the 45th president was elected. It was clear to me the BLM movement; the racial reckoning and disparity awareness could not have gained such power under a different situation.

FUCHSIA HAND-ME-DOWNS

Before we migrated here from Chicago, my twin boys were the only white kids at their preschool and the only US president they knew, was a black man. As a parent, it is so hard not to fantasize about bringing them up in a world where you get to create reality.

I got a tenure track position at Towson. I was grateful. We moved to Baltimore City, I was happy to be back on the East Coast and sent Max and Calder off to kindergarten.

I will never forget the day they came running home saying, “Mom! Mom! Did you know that black people used to be enslaved by white people?!” I could hear my heart cracking open and spilling my leaky watered-down narrative all over the place.

Having long blond hair and hand-me-downs in fuchsia, these boys were often assigned gender by others. They didn’t mind because it was normal. We taught them about evolution, how we are all from Africa, and that assigning a color to gender would be like assigning food to gender. Mommy gets to eat all the chocolate because she is a girl! Since I got pregnant late and the boys arrived early, they were asked to participate in a study. We agreed and took advantage of the perks that came along with it. Nurses would come to our home, observe, and track the boys’ development through cognitive tactile tests. They did beautifully until their last session, the exit interview when they “lost a few points”.

Having long blond hair and hand-me-downs in fuchsia, these boys were often assigned gender by others. They didn’t mind because it was normal. We taught them about evolution, how we are all from Africa, and that assigning a color to gender would be like assigning food to gender. Mommy gets to eat all the chocolate because she is a girl! Since I got pregnant late and the boys arrived early, they were asked to participate in a study. We agreed and took advantage of the perks that came along with it. Nurses would come to our home, observe, and track the boys’ development through cognitive tactile tests. They did beautifully until their last session, the exit interview when they “lost a few points”.

The researcher was different this time and she brought with her this rubber doll family that looked like it came from the 1960s. Very generic. Very Western. Very rubbery. They could be twisted into unnatural positions. I remembered them from the doctor’s offices when I was a kid. She gave the dolls to the boys, who immediately started playing with them. She asked them who the mother and who the father was, and each boy was able to discern this from the size of these strange new creatures (who were definitely assigned gendered colors!). Then she asked who the girl was and who the boy was. Max and Calder just kept right on playing with the dolls. She asked the question again, called them by name, but they still did not answer. She then asked each boy, if they were a girl or a boy. Again, they did not answer but kept on twisting the rubbery dolls into strange positions and experimenting with bounce ability.

The researcher then turned to me in horror and asked, “Don’t they know if they are a girl or a boy?!”

The researcher then turned to me in horror and asked, “Don’t they know if they are a girl or a boy?!”

I laughed and said, “Well, they know that have a penis. I mean, it never really came up.”

Although I have now lived in Baltimore for over 5 years, I have yet to make it to the Inner Harbor to see the fireworks on the 4th of July. I love fireworks, but not crowds. A few years ago, when a friend invited us to his community to see the fireworks, I jumped at the opportunity. It was classic, with swimming pools, hot dogs, and sweet sticky summer hands of little boys. After the fireworks, we carried sleepy little bodies into the back of the car and Calder asked, “Where were all the black people?”

“Excellent question, Calder!” I was so proud—but also horrified. Because I didn’t even notice…

A year or two later, we were taking piano lessons up the street. I was running late, as usual, and little kids never help things speed up.

As the boys were climbing out of the car, in my military mom’s voice I said, “Go! Go! Go! And Max, pick up your stuffed panda from the bottom of the car floor. He is getting even dirtier!”

Max turned to me with great fierceness and said, “How do you know Panda is a boy?! That is racists!”

As with Calder, I was so proud of him, and we were running late already, I just said, “Thank you, Max. You are right. And please continue to keep pointing those things out to me.”

BE THE SILVER LINING

Personally, I believe all the things that are broken about us, are what make us the most interesting. I have done lots of terrible things. I wished for this pandemic. I wanted more time with my boys and less time working. And that is, the best, worst thing I have done! Our jihad (spiritual/inner struggle) is a gift, a bridge to our humanity. It is how we practice gratitude and humility. It is how we ask for forgiveness for ourselves and our ancestors—who no longer can.

Personally, I believe all the things that are broken about us, are what make us the most interesting. I have done lots of terrible things. I wished for this pandemic. I wanted more time with my boys and less time working. And that is, the best, worst thing I have done! Our jihad (spiritual/inner struggle) is a gift, a bridge to our humanity. It is how we practice gratitude and humility. It is how we ask for forgiveness for ourselves and our ancestors—who no longer can.

About

Originally from New York City, Tavia La Follette is a director, designer, curator and performance artist, and professor in the Department of Theatre Arts at Towson University. Tavia earned her MFA in Performance-Pedagogy from the University of Pittsburgh and her PhD in Leadership and Change through Culture and the Arts at Antioch University. She has taught, directed and designed at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, the Carnegie Museum, Colby College, Point Park University, Carnegie Mellon University, Earlham College, the University of Pittsburgh, Chatham University, and at the University of Virginia via the Semester at Sea program. Tavia is the Founder and Director of ArtUp, a non-profit arts organization whose mission is to bridge a language of peace through the actions of art. Currently, Tavia is the director of COFAC CoLab, an incubator for ideas, projects and collaboration. Read more

Originally from New York City, Tavia La Follette is a director, designer, curator and performance artist, and professor in the Department of Theatre Arts at Towson University. Tavia earned her MFA in Performance-Pedagogy from the University of Pittsburgh and her PhD in Leadership and Change through Culture and the Arts at Antioch University. She has taught, directed and designed at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, the Carnegie Museum, Colby College, Point Park University, Carnegie Mellon University, Earlham College, the University of Pittsburgh, Chatham University, and at the University of Virginia via the Semester at Sea program. Tavia is the Founder and Director of ArtUp, a non-profit arts organization whose mission is to bridge a language of peace through the actions of art. Currently, Tavia is the director of COFAC CoLab, an incubator for ideas, projects and collaboration. Read more

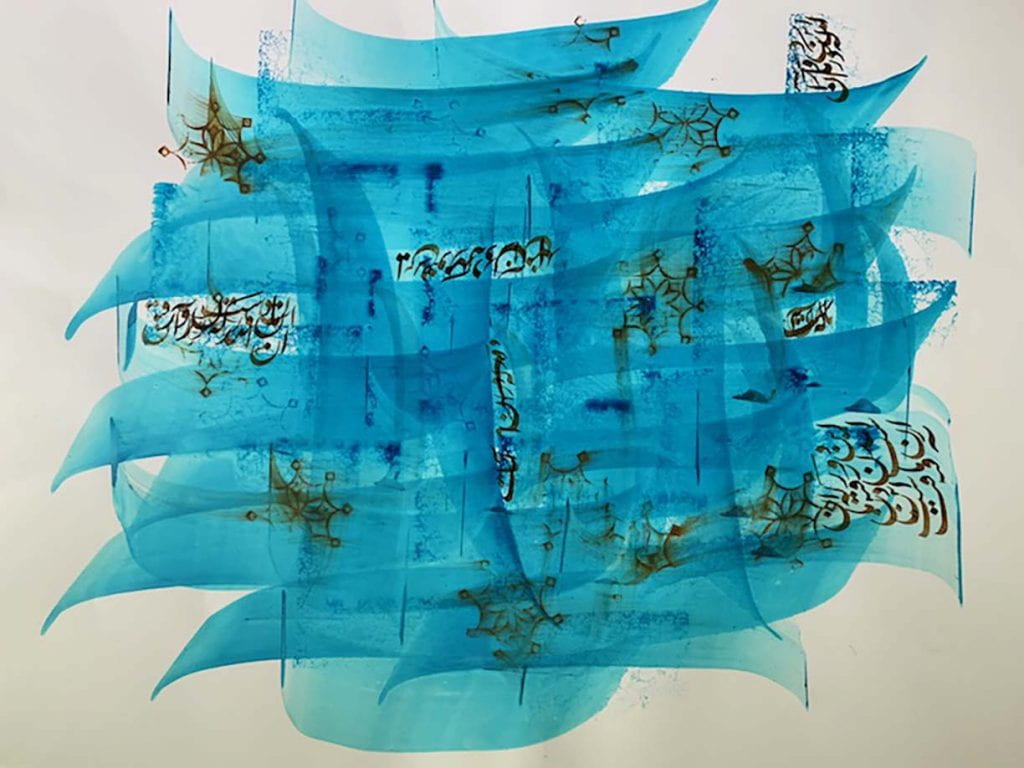

Nahid Tootoonchi

Nahid Tootoonchi