Adapted from a presentation given during a reunion of Lida Lee Tall school students on November 19, 2016.

Much like Towson University, sometimes still called Towson State University, or even Towson State College, the school that would finally be known as the Lida Lee Tall School went through a variety of names.

- 1866-1879: Model School

- 1879-1886: Training School

- 1887-1908: Elementary Department

- 1909-1914: Model School

- 1915-1917: Practice School

- 1918-1925: Elementary School

- 1926-1940: Campus Elementary School

- 1941-1961: Lida Lee Tall School

- 1962-1965: Lida Lee Tall Laboratory School

- 1966-1971: Lida Lee Tall School

- 1972-1991: Lida Lee Tall Learning Resources Center

As the school program transformed and changed direction and scope, the name changed, too. It’s not unusual to hear the school referred to by any one of these names.

While it was the model school, students of the Maryland State Normal School (MSNS) used the facilities only to observe professional teachers in action. Because most MSNS students weren’t up to the academic standards demanded by Professor Newell, he would not allow them to actually teach the elementary students.

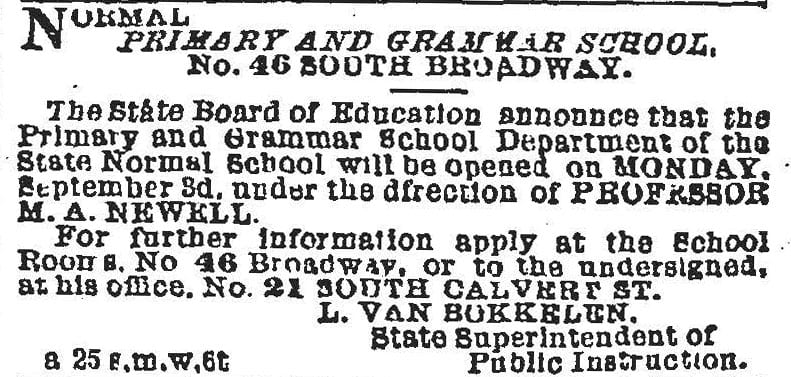

However, from the start, the problem of location was a great difficulty for the schools. When the Model School first opened its doors in September of 1866, it was at 46 Broadway, 2 miles from MSNS’ location at Paca Street. When the model school was so far away, there was little daily interaction between it and the Normal school, which wholly defeated the purpose of having a model school in the first place.

By 1876, both Model and Normal Schools would be in place under one roof with the opening of the Carrollton Building.

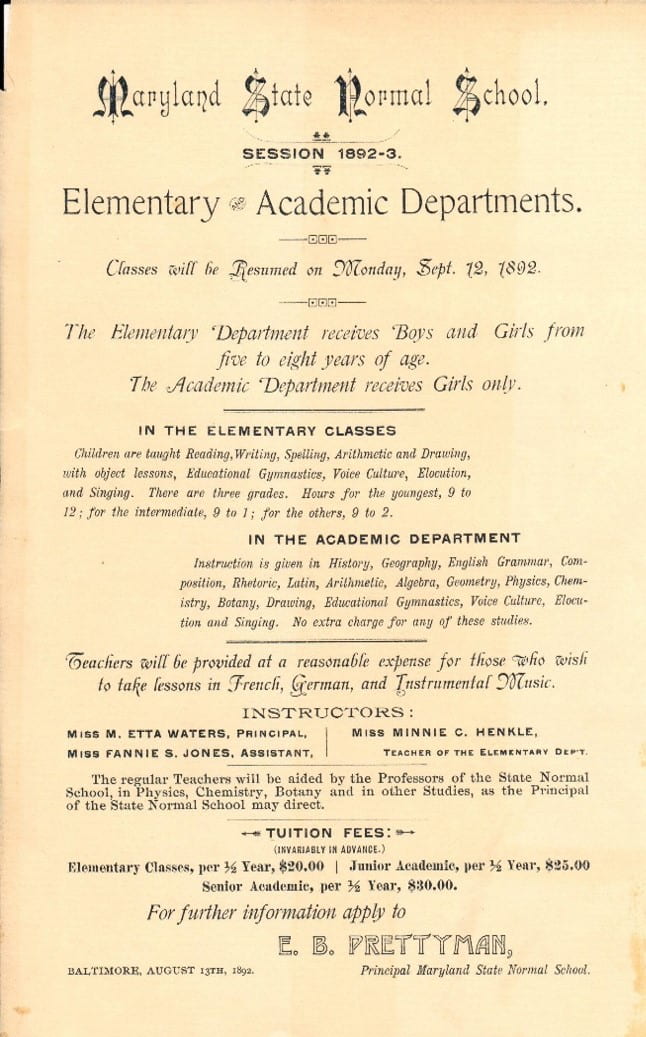

Professor Newell was succeeded by EB Prettyman in 1890, and his tenure was less progressive than Newell’s had been. In fact, the first year that he was in office a graduate named Mary Scarborough said, “We had very little contact that year with the model school.”

Model Become Practice

In 1905, the new principal at MSNS, Dr. George Ward, overhauled much of the administrative and academic standards, including making it mandatory that student teachers do more than just observe at the model school. By 1906, every senior taught one lesson during his or her term of observation and soon the work of student teachers would become much more rigorous. A report noted that “Observation of actual teaching in both Normal and Model Schools with notes and written reports thereon is required of every class.”

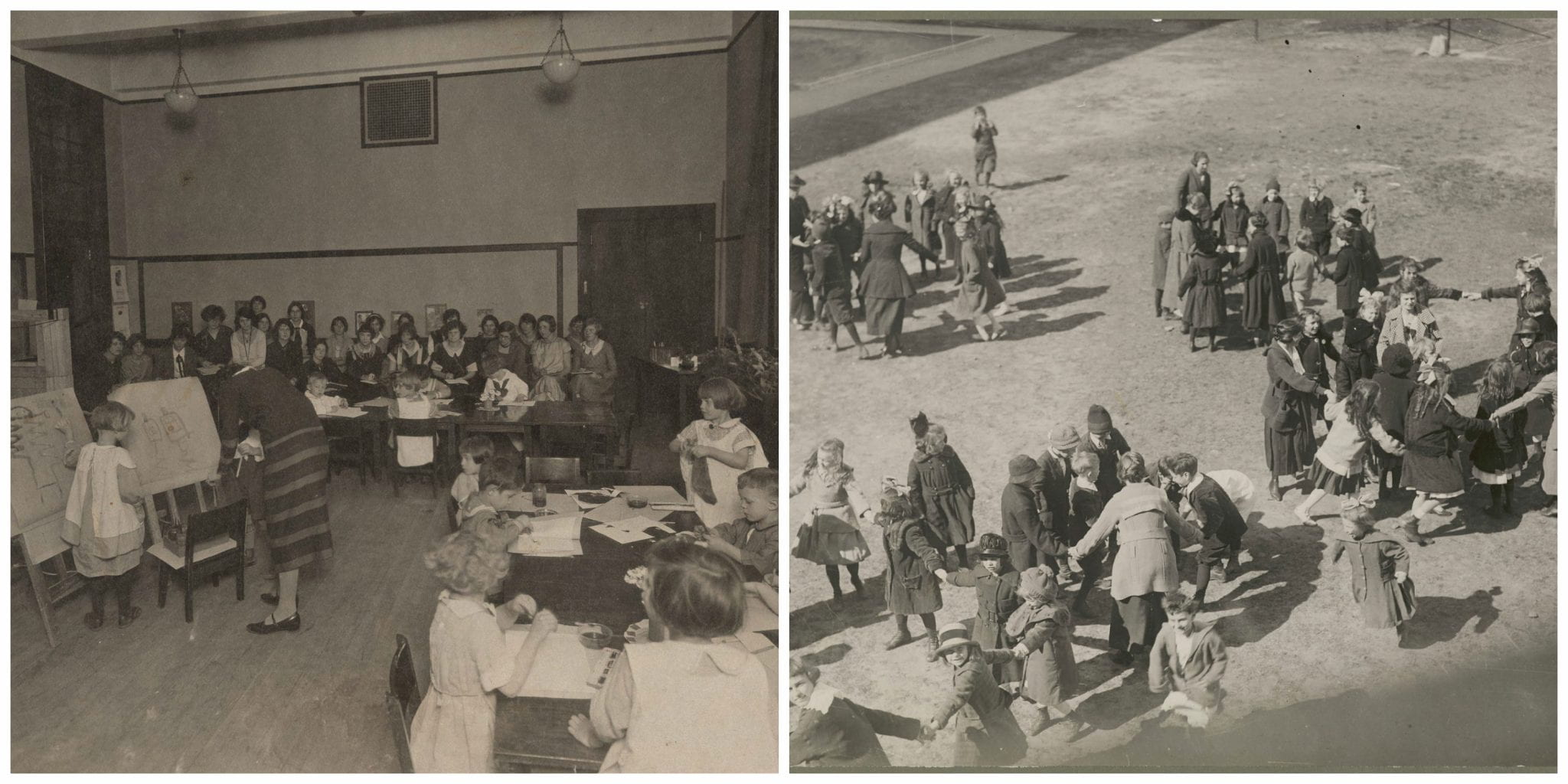

The move to Towson in 1915 improved many things for the school. Not only would more children be able to attend, but there was also now a cafeteria, and a library devoted to the Practice School. Of course, the wide expanse of land also allowed for even more time to be spent doing field work outside the classroom.

The school itself was located on the first floor of what we now call Stephens Hall. The first year, there were 50 pupils, but that enrollment doubled by the following year.

This move also placed the Practice School under the public school system which meant that there was no longer any tuition. Baltimore County paid an amount designed to cover several teachers salaries while the state made up the difference.

At first only students who lived nearby attended, but eventually the school was open to any student who could manage transportation.

Finally in 1932 a separate building was constructed on campus for what was then called the elementary school. Now known as Van Bokkelen Hall, it’s been through its own series of name changes. But it also was not large enough to accommodate the demand. Each class was limited to 30 students and while anyone was welcome to apply, the wait-list was long.

While it was known as the Campus Elementary School when the building was constructed, it became the Lida Lee Tall School in 1942, in honor of Towson’s sixth school leader.

Almost 40 years later, a second building was constructed and christened the Lida Lee Tall School. Designed to fit within the hilly campus topography, the building was somewhat circular. It was designed to accommodate over 400 students and anticipated that 1,440 college students per semester would have training in teaching there. There were twelve classrooms and a kindergarten, a music room, assembly room, an art room, a cafeteria-kitchen, play room, science room, health suite, library, administrative quarters, and group conference rooms. It was an innovative building designed for both the comfort of the children who were schooled their and those who would do research on educational practices.

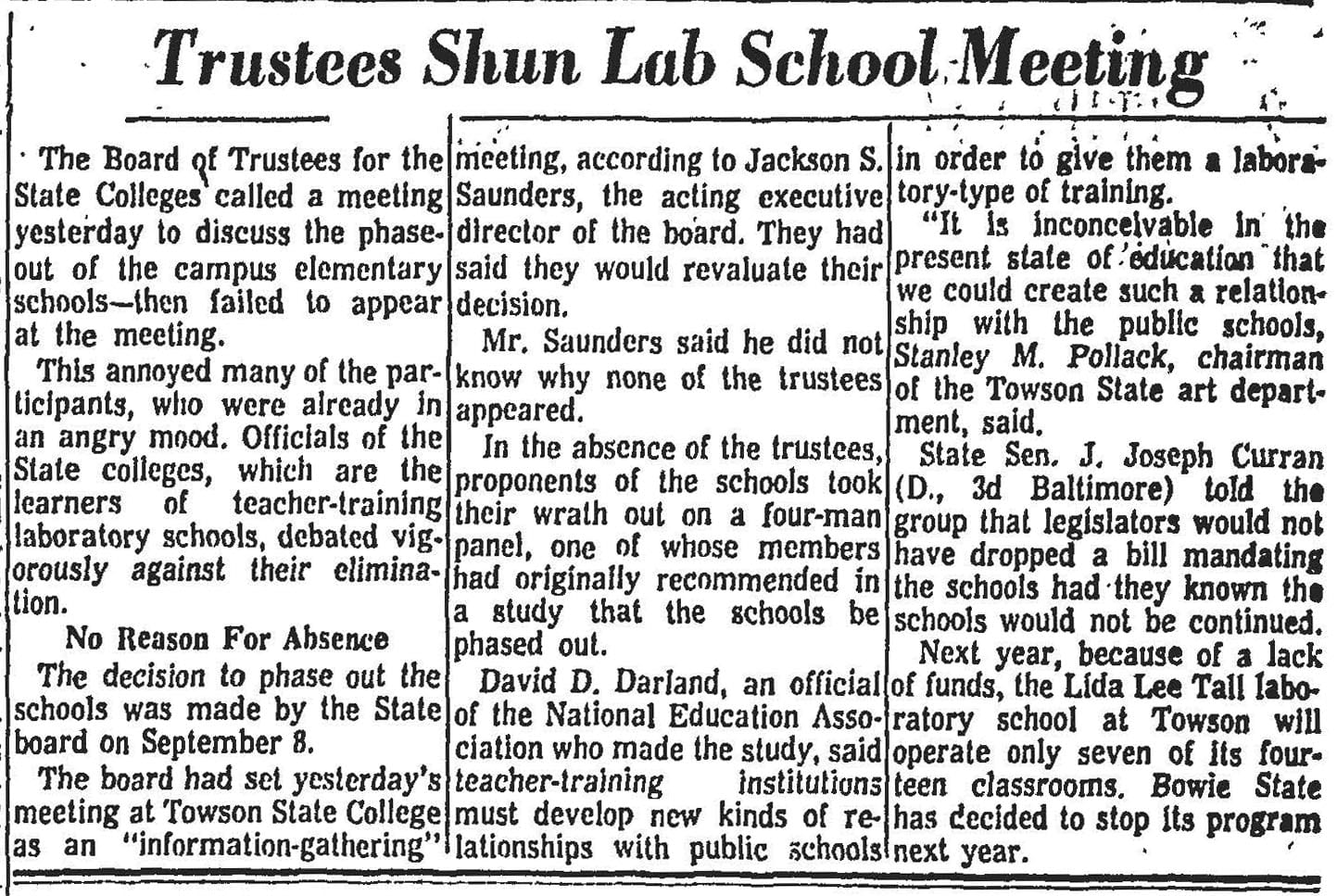

A report from Dr. David Darland, a consultant who worked for the NEA, stated that student teachers needed a variety of school settings from which to learn and given the fiscal constraints, it didn’t make sense for colleges to keep operating laboratory schools which showed only one kind of very unique setting.

It was an argument that had been made time and time again. Dr. Ward himself had said as much in 1908 when suggesting that those who could afford tuition made the school “a select school”.

While the school survived this particular threat, it forever changed how the school would be used by succeeding students.

Part of the fallout from the Darland report was the transformation of the school into a Learning Resources Center. A full-time research coordinator was employed by the school to help facilitate projects run by researchers. A magazine, “Probe”, published the results of many of the experiments run in the school. Observation and demonstration components were still part of the program. The financial woes, however, would continue to mount. The school was again threatened with closing in the 1980s, but was again saved by staunch supporters. At this time the school was placed under control of the Maryland Educational Coordinating Committee.

Eventually, the state budget woes overwhelmed the efforts to keep Lida Lee Tall operating. In the spring of 1991, Governor William Donald Schaefer did not put funding for the school into his 1992 budget, shutting down a 125 year institution. After that the building continued to be used as an early child care center until its demolition in 2006. A new child care center was constructed on campus over by the stadiums on Osler Drive.

Knowledge of Things: What Made the School Unique

Professor Newell was adamant that the old way of doing things was not the most advantageous. He wrote “The traditional order of studies – Alphabet, Spelling, Reading, Writing – has been completely reversed, and the new order is Writing, Reading, Spelling”. The argument was that by writing first, reading and spelling would naturally fall into place. Newell also was adamant that the “ ‘extras’ of the boarding school” – languages and arts – were part of the regular curriculum for the students of the Model School.

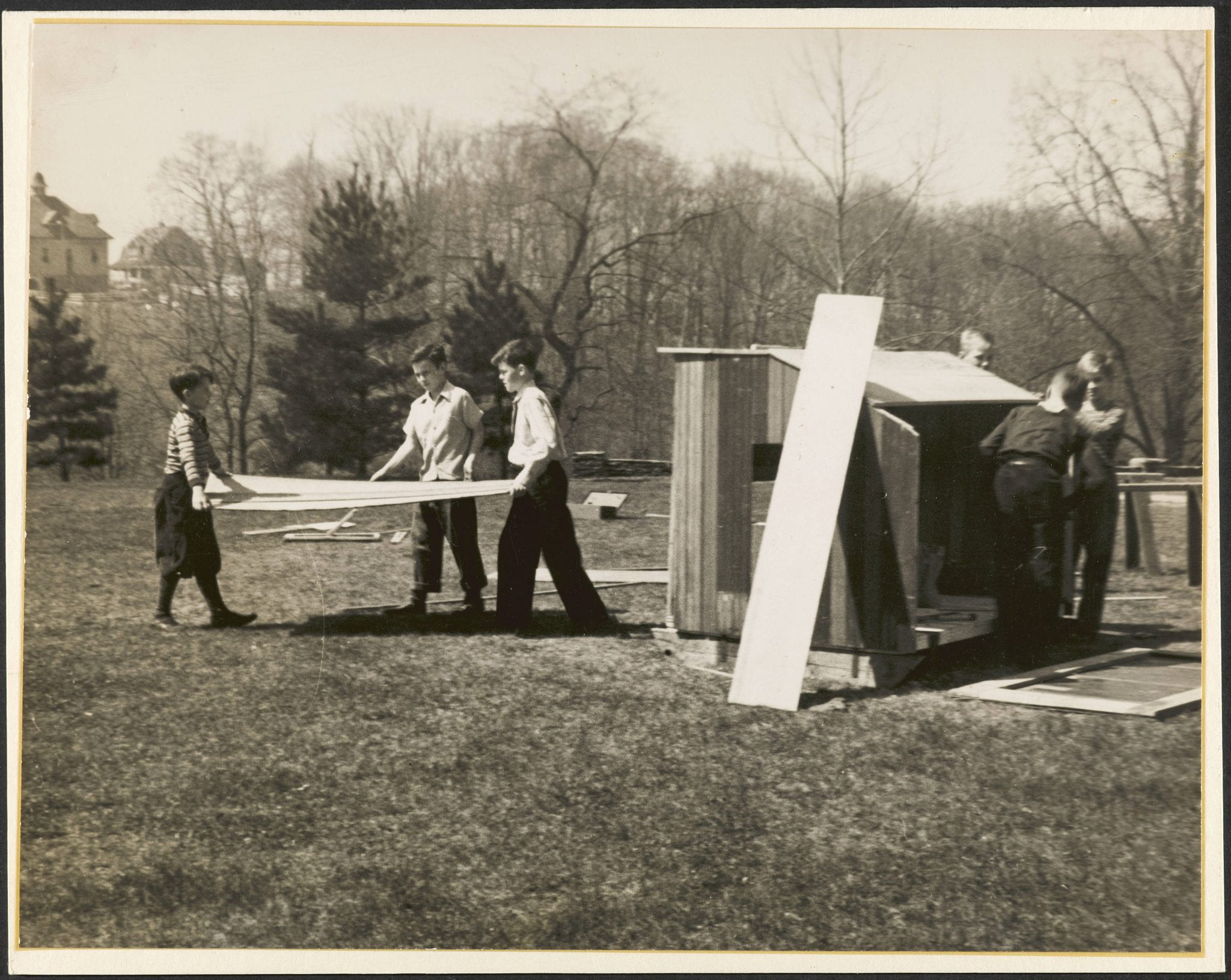

This is the crux of what made this school so unique, what John Dewey called “learning by doing”. From the very start, students were encouraged to understand through exploration. Whether it be building a chicken coop to understanding soil conservation or even just helping maintain the bathrooms. A Baltimore Sun article from 1949 described all the projects the classes were undertaking and they included making hand-dipped tallow candles, creating a rock garden, and even many field trips around the campus and beyond. That article also talked about how the children were often so busy out and learning that you wouldn’t find them within “the confining four walls of the classroom”.

But that freedom of exploration came with the acknowledgement that these students were also, in some ways, test subjects. While the first 30 years or so were devoted to just observing the elementary students, eventually student teachers were making their first instructional forays by practicing with the elementary students. And ultimately, after the creation of the Learning Resources Center, researchers began testing out their theories of educational practices on students, not just practicing the craft of teaching itself.

And finally, Te-Pa-Chi was a significant partner in the running of the school. This organization supported events like Glen Day and parent breakfasts and even began child education classes for parents of the elementary school children. The school’s continued endurance in the face of so much financial pressure is due in no small part to the steadfast loyalty of this group who lobbied both the Towson administration and state legislators to continue to fund Lida Lee Tall.

Today, as so many schools try to find the magic fix for education, the University of North Carolina has mandated that eight of its institutions open laboratory schools in low-performing public school districts.

So while Lida Lee Tall is no more, I know that the legacy of that school, and the schools like it that blossomed up during the 19th and 20th centuries, continues.

We’ve recently created the Lida Lee Tall School Legacy Fund to help us continue to collect and preserve materials from the 125-year history of the school. And we hope to have many more reunions with former LLT students in the future. Contact us at spcoll@towson.edu if you want to be included in those plans!