It happens like clockwork — the days get shorter, there’s a chill in the air, and people contact us here in the Special Collections and University Archives department to ask about Auburn House.

We can understand why. It’s a lovely old house on the edge of campus. You only get to go there for special events. Oh, and it might be haunted. Is it haunted? “Tell us about Martha!” people say. And, well. Let me tell you about the Auburn House first — who built it, why they built it, and how Towson acquired it. Along the way, we’ll get to Martha. You might not like it, but we’ll get there.

The beginning . . .

In Colonial America, a wealthy gentleman named Charles Ridgely II inherited some land from his grandfather, received more when he married his wife, and acquired still more as he grew more and more influential. In 1745, he purchased 1500 acres of land named “Northampton” in Baltimore County.

Here he and his son, Captain Charles Ridgely III, established a tobacco plantation and ironworks. Captain Ridgely began construction of a house, Hampton Mansion, in 1783. The estate was so large that during construction of Hampton Mansion it is reported that the workers would be sent home at about 3 in the afternoon so they could avoid the wolves that still roamed the heavily forested wilderness at the time. Upon its completion in 1790, it was the largest private residence in the United States.

Captain Ridgely and his wife, Rebecca, had no children, and thanks to the laws of primogeniture at the time, his nephew, Charles Canan Ridgely was set to inherit the estate when Captain Ridgely died in 1790, very soon after Hampton Mansion was completed.

Charles Canan Ridgely and Rebecca Ridgely purportedly did not get along. H. George Hahn and Carl Behm in their 1977 book, Towson: A Pictorial History of a Maryland Town write that they “developed an antagonism over his treating her ‘with the Greatest Disrespect and Slights.’ For the surrender of all further claim to her late husband’s property at Hampton, the widow received from her nephew a tract of 244 1/4 acres off the York Turnpike originally called Demitt’s Delight.”

It was here that a dower house for Rebecca Ridgely was constructed and named Auburn House. The name came from a poem by Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village.

Many think that Auburn is a smaller version of Hampton Mansion. Both are examples of late Georgian architecture. Both are constructed of stone with a stucco exterior. And the layout of the rooms on each floor along a central hallway is also similar.

![By Preservation Maryland (Hampton Mansion, exterior) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp.towson.edu/scua/files/2016/10/Hampton_Mansion-1hrwg1m.jpg)

Rebecca Ridgely moved into Auburn House in 1791 and lived there for about 20 years. She died in 1812, and 4 years later, the house was owned by John Yellott, a relative of the Ridgely family. The house then passed to Benjamin P. Moore, and finally was bought by Henry C. Turnbull as a home for himself and his new wife.

Turnbull’s father, William, was a house furnishings merchant. The Turnbull Mansion still stands in the Union Square neighborhood in southwest Baltimore at Lombard and Stricker Street.

Turnbull was very proud of the “Bride” and “Groom” elm trees that stood outside the door at Auburn House. Two English elms were planted during construction of the house and would eventually grow to be 125 feet tall.

As the Towerlight reported in 1985, “One story relates how the Turnbull family . . . purchased an old fire engine from the local fire department whose pump would be used to spray water on the immense trees. The trees even survived a huge fire that struck in 1849, gutting the mansion but leaving the trees basically unscathed.”

On October 29, 1849, there was a terrible rainstorm, and at some point, the Auburn House caught on fire.

The Baltimore Sun, reporting two days later, noted that “As is customary in the country, advantage was taken of the heavy rain to burn out the chimneys of the dwelling. From some cause, perhaps a defect in the chimney, the interior of the roof caught fire; the roof itself being zinc, there was no chance for the flames to burn through and give the rain a chance to act on the fire.”

The house was a total loss.

The only things that survived the fire were the foundation, and three basement doors. Turnbull decided to rebuild an exact replica of the first house.

Turnbull and family owned the house until about 1915 when it was acquired by John Fife Symington. He and his wife renamed the house “Kenoway House”, perhaps after a Scottish village. They seemed very active in Baltimore society and often hosted events at the house. Symington also changed the space, adding a two-story service wing and removing much of the Victorian-era ornamentation that decorated the house.

In 1944, the house was deeded to Sheppard Pratt Hospital. It was used as a family residence by the medical director, Dr. Harry Murdock, for twenty years. And then John Moro, the plant supervisor for Sheppard Pratt, moved his wife Emma and their children into the house from 1965 until 1971.

In 1971, Towson State College (TSC), which had been a near neighbor of Auburn House since the school’s move to Towson in 1915, acquired 23 acres of land from Sheppard Pratt, and the house was included in that parcel. The idea was that the school would use the land to build additional parking and athletic fields and ultimately it is where the stadiums and child care center would be constructed.

Auburn House’s existence on the land seems to almost be an afterthought, but it became much more important once President Fisher moved his family out of Glen Esk and off of campus. Glen Esk had been the place on campus for the President to entertain, but with his move Glen Esk transitioned from a place where the President entertained to the badly needed space for the Counseling Center. The natural next step was to use Auburn House for the President’s gathering space, but there was opposition.

STC’s Advisory Committee decided that a dining club should be formed and offer memberships for faculty, alumni, andstudents, as well as members of the local community. This would generate not only income for the institution, but also create networking opportunities for interested parties. The Development Office invited people to join this new venture called the Towson Club through direct invitations and ads in the Towerlight.

At first it was thought that Glen Esk would be the meeting spot and so the club was granted a license to serve alcohol at that location. But when the school acquired Auburn House, it asked the Baltimore County Liquor Board to transfer the license there.

Neighborhoods close to that area of campus opposed the transfer of the license as did other bar owners in Towson, and eventually the transfer was denied. An appeal was also denied, and so the club had to apply for a new license altogether. In the meantime, the Board of Public Works was working out what the state would charge the club for rent of the building. In 1972, the Towerlight reported “A $12,000 yearly lease was placed upon the Club. Reasons were submitted as to the invalidity of this cost. In September, 1972, the rent was lowered to $6,000 provided the club profited sufficiently to pay it.”

As the house sat vacant waiting the outcome of both of these decisions, it became a target of vandals. By December of 1973, the Towerlight reported “it is estimated that over $100,000 will be needed to put the house in suitable condition.” The story goes on to quote Bill Brown, member of the office of Federal and Foundation Programs: “When I first saw the house about one and a half years ago, I would have estimated that $30,000 would have put it back in shape, but now, with all the vandalism that has been done both inside and outside the house, the sum is beyond reach without outside help.”

It was decided that one way to save the house would be to have it listed as a historical site. Doing so would not only give the house cache, it would mean there would be money to help restore it. However, the request was rejected as it was thought that Auburn House was not significant enough to the nation’s history. Meanwhile, Hampton Mansion had been designated as a National Historic Site in 1948, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and would be acquired by the National Park Service in 1979.

By the fall of 1975, these barriers were all but cleared. The liquor license was granted the previous spring. The Towson Club began signing up members in August and had 400 by the end of October. And a lease between the state and the Towson State College Foundation, Inc. had been agreed to by both parties and the Foundation was preparing to begin restoration with an eye at opening the house in July of 1976.

When all was said and done, the money for the repairs and refurnishing of Auburn House totaled over $500,000 — the equivalent of over $2,000,000 in today’s money. It was named to the National Register of Historic Places and received $20,000 in federal preservation funds. The rest of the money that restored the house came from the fees and dues from the Towson Club members.

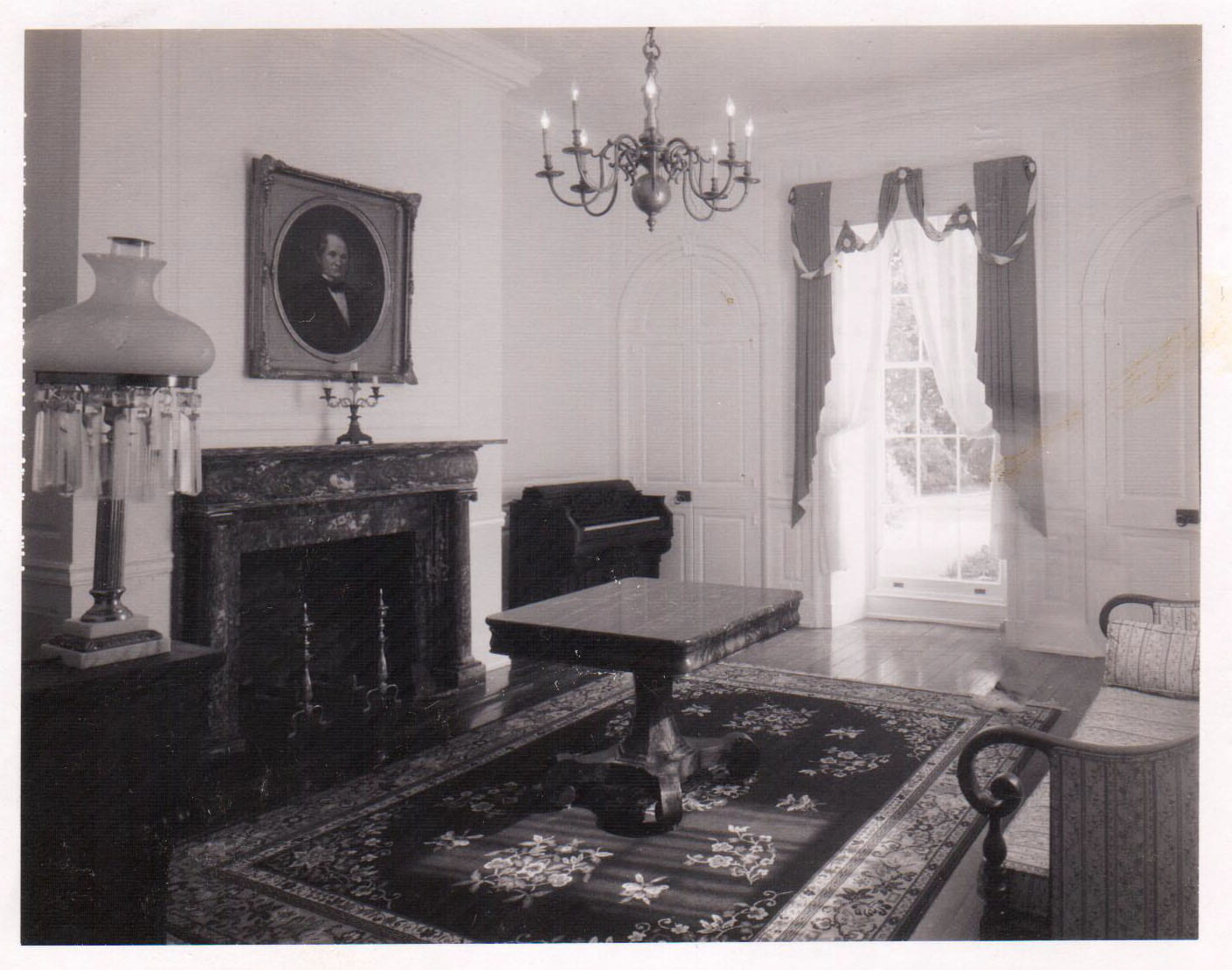

Th house itself wasn’t ready for entertaining until that November. Part of the basement was turned into a bar named the Rathskeller. It featured exposed brick and stone walls to give it a rustic feel. The rest of the basement and the first floor was used as a dining club with white linen tablecloths and a upscale fare. “The menu,” reported in the Towerlight in November of 1982, the food offerings were”is a small but boastful one, offering the members filet mignon, chateaubriand, and cordon bleau.” There were also burgers, crab cakes, and lighter fare including salads and fresh fruit.

By that 1982 story, the club had been renamed as the University Club. It had about 1400 members It hosted special events like trips to watch the Preakness and trips to Atlantic City, NJ. Themed dining events attracted alumni guests. As the Towerlight reported in that same story:

On Wednesdays, University Club features a luncheon fashion show. Kitty Dale, founder and proprietor of the Kitty Dale Modeling Agency, explains, “It’s informal tea-room modeling. The girls model fashions from local shops.”

They walk from table to table, show the particular piece they’re wearing and answer any questions. It’s more of a social activity than any kind of high-pressure selling.

And on Thursdays, the University Club hosted “International Night”, exploring cuisine from different cultures.

Attempts were made to entice students to come to Auburn House. As the 1982 story continues, “During Homecoming, Colonel White, the president of the club, offered free beer to Towson State students if Towson won the Morgan State game. Towson won, but there wasn’t the large crowd the Rathskeller anticipated.”

“‘Most students aren’t familiar with the club and have very little interest in it,’ said one Towson student.”

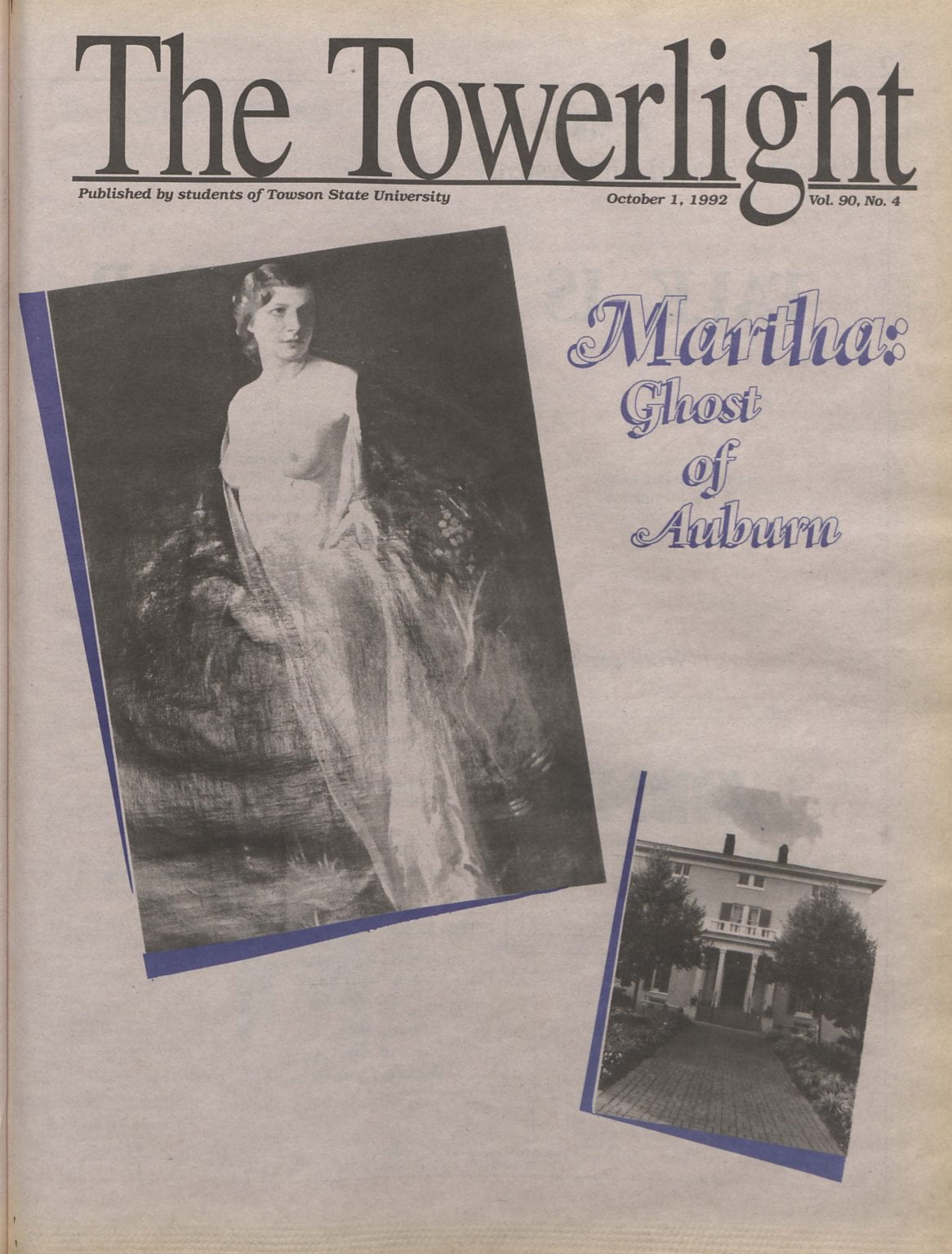

This article is also the first where there is mention of a ghost.

About Martha . . .

And here is where the legend of Martha, the Auburn Ghost, most likely came to life, spurred by the history of the 1849 fire. There are thoughts that the ghost was a serving girl caught in the fire. Some even say that Martha was holding a child in her arms when she died. There are stories of lights going out, footsteps, pages turning in books, and open windows. There’s even a painting that is supposedly of Martha, but it’s dated 1931, so that’s well after the fire.

Here is the rest of the Baltimore Sun account of the night in question: “From the density of the smoke, it was impossible for any one to approach the place of conflagration in time to be of service. The only thing that could be done was to save the furniture, etc., which was done, subject, of course, to all the damages of a hasty removal and a drenching rain. The loss is estimated at $6,000”.

There is no mention of anyone perishing in the fire. Given that the story is buried on page 2 of a very densely written newspaper, and that the story right after this is about a runaway horse in Saratoga, New York, I think that if a maid (and maybe a child!) had died in that fire, there would have been a much more sensational headline than the one it bears: Destructive Fire in Baltimore County.

So. If there is a ghost, she may very well be Martha, but she didn’t come from that 1849 fire.

In the 1982 Towerlight article where the ghost is first mentioned the building manager, Mark Williamson, says “The reports of ghosts are pretty infrequent if existent at all.”

(Sorry. Please don’t be mad.)

Back to our non-spectral story . . .

By 1985, the University Club was in trouble. While it had attracted some members, there wasn’t enough profit to pay the lease as well as debt owed to the state for use of the athletic facilities by club members, and to continue to keep the place open. And what few profits there were came not from membership dues but from the fees paid to the club for holding receptions and luncheons at the house.

In the meantime, the two beautiful English elm trees that stood outside the club entrance were scheduled for removal. Dr. Lois O’Dell, a Biology professor at TSU was interviewed by the Towerlight in November of 1985 about the loss of the trees to Dutch elm disease. She “stated that the trees ‘probably would have died anyway’ due to what she termed ‘improper pruning technique’ referring to a pruning the trees had undergone approximately three years ago. When she saw the trees after the pruning, she states that she ‘shook my head in dismay. I knew the trees were doomed.'”

Two trees were planted in their place and continue to grace the entrance of Auburn House.

In the spring of 1986, the University Club re-opened. It had come to an agreement for a plan with the state to pay off the debt it owed in nine years. But the club wouldn’t last that long. Ultimately, the goal of a club with members of faculty, students, alumni, and community members wasn’t able to succeed at Towson. By 1992 when it finally closed, it had only 900 members.

The Auburn House became the Alumni House at Auburn, a place reserved for special events, whether it be alumni or school events, or rented out to the public. By then the Rathskeller had moved to the University Union, and the bar in the basement of Auburn House was called “Martha’s Pub.” For a while, Martha’s Pub was open to the public even as the rest of the house was reserved for specific events. But more and more University events were being held at Pub Smedley, now known as The University Club at the Towson University Marriott Hotel. Pub Smedley at the time was decorated with a TSU sports theme.

Eventually Martha’s Pub closed its weekly operations and was open only for special events.

In 1999, the house became the home to the Auburn Society, an “Institute for Learning in Retirement”. The society was open to individuals over the age of 50 and offered non-credit classes and study groups as well as opportunities for travel. The group had to pay a fee for use of the Auburn House as well.

Eventually the Auburn Society began meeting in a different building on campus, and by 2006, the name was changed to the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute because of a grant from the Bernard Osher Foundation.

Today, the house is managed by the President’s Office, and continues to be used for special events like pre-game receptions and private parties and weddings. And in keeping with its new role, it has been decorated with many of the portraits of past school leaders.

Auburn House will undergo a renovation this spring, adding some better accessibility solutions.

After 45 years, it has become a true piece of Towson University’s history.