To celebrate the inauguration of Kim Schatzel as Towson University’s 14th leader, we are looking back at the past leaders of the school. These essays are from a book we helped craft, Towson University: The First 150 Years.

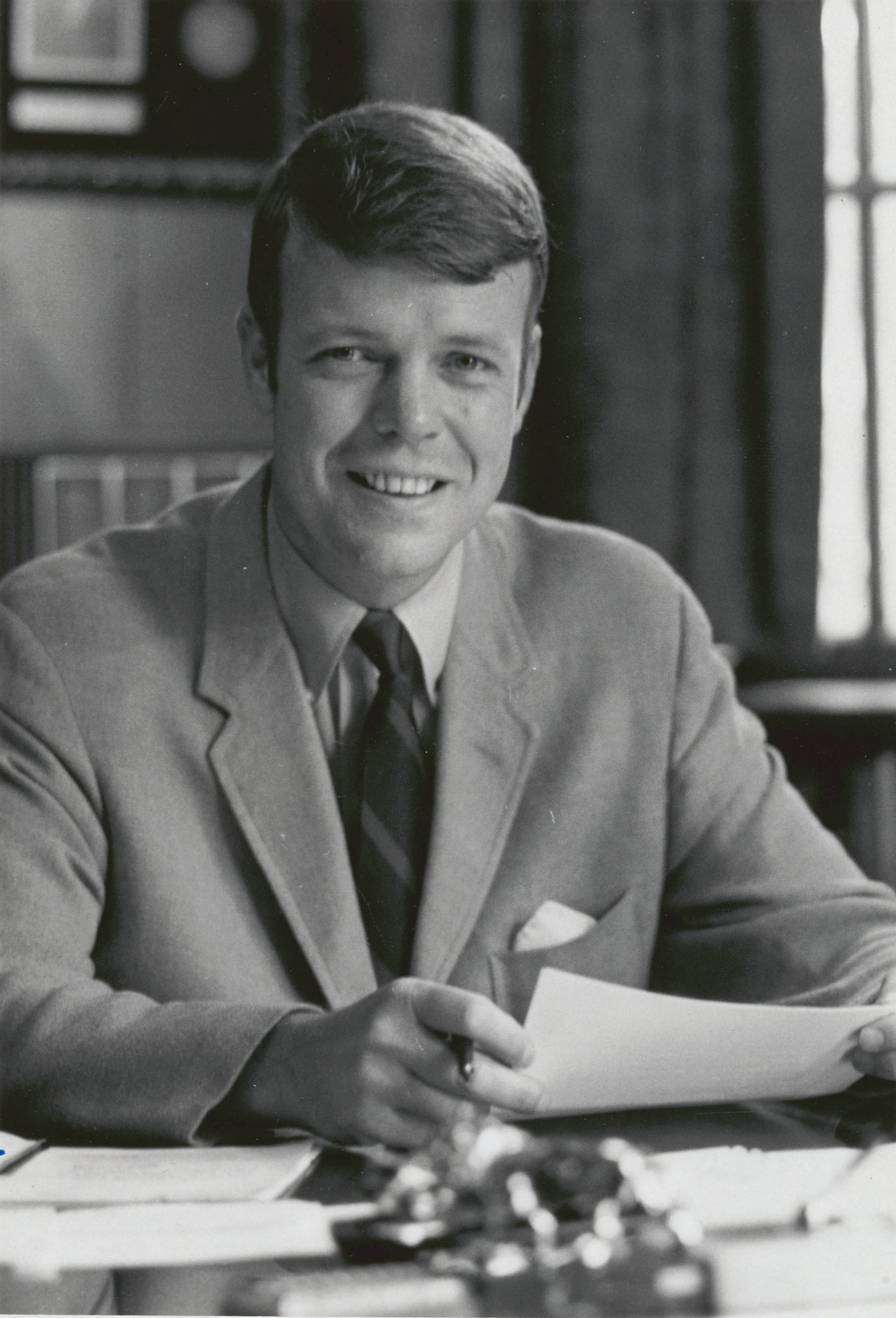

In 1969 Hawkins retired and handed the leadership over to the first president whose experience in education lay outside the state of Maryland and the first whose background did not include teacher education. Born in Illinois, Dr. James Lee Fisher took time off from his education to serve in the Marine Corps Intelligence from 1951-1954, finished an undergraduate degree in history from Illinois State University, taught in high school, then joined the administration at Northwestern University while finishing his doctorate from the same institution. When he accepted the presidency at Towson State College at age 38, he had served six years at Northwestern University, including two years as a vice president.

When Fisher arrived at Towson, it had already gone through the transition of becoming a liberal arts college and was expanding rapidly. While Hawkins expanded the campus footprint with 11 new buildings and its enrollment from 600 students to 8,000, Fisher added another 11 buildings and saw enrollment climb to over 15,000 students.

It was Fisher who expanded the administrative offices of the college, creating four vice-presidential positions, establishing five academic deans, founding the Academic Council as a legislative and advisory body of faculty and students, and creating the Office of Institutional Development. In terms of enhancing academics, Fisher also oversaw the addition of a winter session, expanded graduate and continuing education programs, and added new programs in nursing, occupational therapy and business.

But whereas Hawkins oversaw growth during a time of relative peace, Fisher’s presidency occurred at a time of great national and local turmoil. In 1970, after the shootings at Kent State, colleges scrambled to address the growing unrest on campuses across the country. Fisher met with students to listen to their views and to keep the campus safe in the midst of such turbulence. He was appointed as a consultant to Robert Finch, a White House adviser to [President] Nixon who was charged with making recommendations regarding campus protests. That same year, members of the Black Student Union on campus marched to the Administration Building and presented Fisher with a list of demands regarding integration on campus. Fisher denied the hanging of an exhibit by photographer M. Richard Kirstel. The artist hung the show on campus anyway and was arrested for trespassing. In 1972, reacting to individuals protesting the presence of United States Marine recruiters on campus, Fisher had the protesters arrested for trespassing. Although he was a firm proponent of the right to civil disobedience, he also insisted that protesters be accountable for their actions.

Fisher pursued a high profile as a college president and sought the same high profile for the college, which many believed had been too often ignored by state government and by others in Maryland higher education. The general public tended to continue to view Towson as a small teachers college rather than a growing arts and science college.

Fisher’s frustration with what he perceived as the state’s disregard for Towson’s potential was underscored by the fight to have the name changed in 1976. Fisher maintained that the name change was necessary to attract prospective students and add credence to the work done on campus. Governor Mandel vetoed the change, fearing it would lead all the other state colleges to want name changes. After specific guidelines were created to establish the difference between a college and a university, Towson State College became Towson State University on July 1, 1976.

By 1978, when Fisher resigned to become the president of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education in Washington, DC, Towson State University had grown to become an institution much different from its roots in the state normal school. It continued to be the leader in preparing teachers for Maryland schools, but it was now much more than that.