In February of 1944, M. Theresa Wiedefeld, President of the State Teachers College at Towson (STC) and member of Class of 1904, co-authored a letter with the Alumni Association President, Myrtle Markley Groshans, and published it in a special newsletter called the “Alumni Victory News”.

They were making the case for the establishment of the Alumni Victory Pool Fund.

“We, like all colleges and universities throughout the country, are concerned about the future of our men now on combat duty,” wrote Wiedefeld and Groshans. “We know that we must make post-war plans to rehabilitate them socially and spiritually. The change brought about in them by the experiences of this horrible war will make it difficult for them to adjust to civilian life. Unless those of us at home prepare to help them there will be a repetition of conditions which followed World War I. Then, too many men became greatly embittered by what they found. They accused those who stayed at home of profiteering on the altar of their sacrifice. They cursed the nation for which they had suffered and many felt that their sacrifices had been in vain. We must not permit a repetition of that condition. We cannot do much. We can do something.”

Wiedefeld’s concern about the treatment of soldiers after World War I was not without cause.

So follows a quick and probably incomplete history lesson about things not exactly related to Towson:

At the end of World War I President Calvin Coolidge refused to pay bonuses to veterans. The bonus pay was a practice begun in 1776 to try and compensate soldiers for what they could have earned had they not enlisted. In 1924, Coolidge stated “Patriotism which is bought and paid for is not patriotism” and vetoed a bill which would have awarded veterans additional pay.

However Congress overrode Coolidge’s veto and the World War Adjusted Compensation Act came into law in May of 1924.

The bonuses, however, were more like IOUs. They were certificates averaging about $1500, but they were set to mature in 20 years, not offer immediate pay-outs.

Financing the war meant a quick increase in government spending — although the US was only involved for 19 months of the war, by the time it ended over 4 million people had served. This meant contracts for munitions, transportation, food, clothing, etc. After the war ended, much of that productivity went into steep decline, and the world’s economy followed suit. Multiple recessions and depressions rocked the globe, ultimately bottoming out in the Great Depression which struck the US in 1929.

For returning veterans, these problems just compounded the usual issues with re-entering civilian life, particularly the problem with unemployment. A certificate that matured in 20 years was not useful to people who needed help more immediately.

And so rose the Bonus Army a protest movement of at least 15,000 veterans and their families which gathered in DC for a month and a half in the summer of 1932 and demanded immediate payout of their certificates.

Ultimately, four men lost their lives as the US Army cleared the camp they’d occupied.

In 1936, Congress passed the Adjusted Compensation Act which meant the bonds could finally be redeemed for cash.

I’m certain that in 1944, just a few short years after the Bonus Army got their payment that the experiences of the WWI veterans weighed heavily on Dr. Wiedefeld’s mind.

The Alumni Association’s desire to build a swimming pool in honor of the veterans of the State Teacher’s College at Towson was just the most visible mark of how the school community responded to the WWII crisis.

In other, more subtle ways, the school had been supporting soldiers almost from the very start of the war.

In 1941, Rebecca Tansil, the registrar and business manager for the school wrote a newsletter to members of the armed forces. She wrote it because a staff member of the Tower Light, the school newspaper, had decided to send copies of the paper to every member in the service.

We only have a draft of that first newsletter, and it’s chatty and informative. Tansil includes information about school enrollment — down, as it would be during the entire war. She reports about the soccer season as many of the servicemen had played under Doc Minnegan. There are reports about the new gymnasium being constructed — ultimately it would be completed and named Wiedefeld Gymnasium, but the war-time economy slowed the progress.

This first newsletter sets the tone for what would come. Soldiers far from home hungered for news about the familiar and the faculty and staff and students at STC were doing their best to keep the service members up-to-date.

But the newsletters began to take on a different role other than a chatty diversion from the monotony of training or the chaos of the battlefield. They became information centers. “The newsletter today is quite different from the first one I wrote in the summer of 1941 when it went to five alumni!” Tansil wrote in 1943.

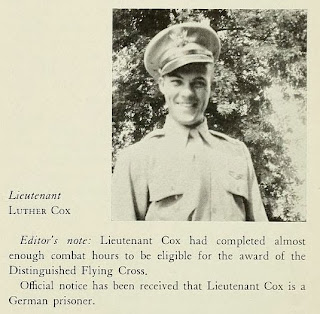

Tansil reported not only what was happening at the school, but shared information about where service members were — if it could be divulged. “I never thought I’d be the least bit interested in where any fellows were” wrote John McCauley as reported in a newsletter in 1943. “But I was really anxious to know where those STC classmates of mine had been scattered.” Tansil reported who had died, who was missing in action, who had become a prisoner of war.

By December of 1942, the school had almost 100 names on the “service rolls” and expected to add many more. And Tansil talked about what was going on at Towson to aid the war effort.

In the spring of 1943, she writes “It has been difficult to keep janitorial help, dormitory help, and farm help and students now help out in many emergencies.” Students and faculty grew Victory Gardens. The elementary students raised ducks and chickens which would later be sold to their families to help food production. “Tuesday night,” she writes later in the newsletter. “the Glee Club is going down to the U.S.O. headquarters to sing for the boys.”

And the service members were grateful. “I welcomed my copy of the Newsletter today as if it were an old friend from home” wrote James O’Connor in the summer of 1943. “When I opened it an officer, noting the ten typewritten pages, remarked, ‘That’s the kind of letter to receive!'”

When those in service visited the school on furlough, often in uniform, the staff made sure to take a photograph and the alumni and staff worked together to create a scrapbook with one page for each service member.

As the war waged on, the effects on campus as reported to the service members were great.

In 1944 Dr. Wiedefeld gave a radio address for WCAO before the Glee Club sang: “Ladies and gentleman — On previous occasions when you listened to a Teachers College Glee Club program you heard a chorus of mixed voices. Today you miss the tenors and basses. The women students are carrying on without the help of their male colleagues”. (We have a recording of that performance but it is on a huge 78 rpm records.)

By August of 1944, Tansil had joined the United States Naval Reserve and the newsletters were taken over by Doc Minnegan, who taught Physical Education. However, Minnegan himself went to work with the Special Service Division, Athletic Branch, at the very end of the war.

In June of 1945 — after the Allies took Europe but before the war was over in the Pacific theater, Minnegan reported “This war-time ceremony was different from the traditional graduation exercises. Many graduates simply took time out from regular teaching jobs to attend the commencement. Only 52 graduates were awarded the B.S. degree. Not a man received a diploma. The parking lot was empty.”

The newsletters ended after September of 1945, as the school and nation turned their focus towards a post-war reality. But they had done their job, connecting the entire community with those in the armed forces so their sacrifices would never be taken for granted.

“We are trying hard to hold things together for you,” Wiedefeld wrote in January of 1945. “Feeling sure at all times that you will be so far ahead of us in so many ways that we can never be ready for you.”

The newsletters, correspondence, and photographs have all been preserved in our World War II collection.

Today, Towson University’s Military & Veterans Center works to support veteran students with advice about financial aid, student groups, and career counseling.