Apr 9, 2018 | networking, trends

As Facebook reels from a privacy scandal, some of its most popular users are lashing out over declining traffic, policy changes and financial complaints.

Source: Facebook’s Other Critics: Its Viral Stars – The New York Times

Apr 9, 2018 | algo, mobile, trends

“We are on the verge of a new era of human-computer interaction,” says Keiichi Matsuda, Leap Motion’s VP of design and global creative director.

Source: Leap Motion’s “Virtual Wearables” May Be The Future Of Computing

Apr 4, 2018 | mobile, networking, trends

Facebook said Wednesday that most of its 2 billion users likely have had their personal information scraped and shared by third-party developers without their explicit permission.

Source: Facebook said the personal data of most of its 2 billion users has been collected and shared with outsiders – The Washington Post

See also: Accessing Your Facebook Data

Apr 4, 2018 | trends, video

What’s really going to kick the addressable revolution into overdrive is the rise of ACR (automated content recognition) data. If you’re unfamiliar, ACR is a technology used to automatically detect and index content that is playing on television in real-time. As a result, brands are able to use this information to determine when a given consumer sees their ad. As ACR data becomes more widespread, the sky’s the limit for addressable TV.

Source: How an Acronym You’ve Probably Never Heard of Will Change TV Advertising Forever – Adweek

Mar 31, 2018 | networking, trends

The difference between getting news from an RSS reader and getting it from Facebook or Twitter or Nuzzel or Apple News is a bit like the difference between a Vegas buffet and an a la carte menu. In either case, you decide what you actually want to consume. But the buffet gives you a whole world of options you otherwise might never have seen.

Source: RSS Readers Are Due for a Comeback: Feedly, The Old Reader, Inoreader | WIRED

Mar 31, 2018 | mobile, networking, trends

The more benign leaks merely cost Facebook a bit of competitive advantage. We’ve learned it’s building a smart speaker, a standalone VR headset and a Houseparty split-screen video chat clone.

Yet policy-focused leaks have exacerbated the backlash against Facebook, putting more pressure on the conscience of employees. As blame fell to Facebook for Trump’s election, word of Facebook prototyping a censorship tool for operating in China escaped, triggering questions about its respect for human rights and free speech. Facebook’s content rulebook got out alongside disturbing tales of the filth the company’s contracted moderators have to sift through. Its ad targeting was revealed to be able to pinpoint emotionally vulnerable teens.

In recent weeks, the leaks have accelerated to a maddening pace in the wake of Facebook’s soggy apologies regarding the Cambridge Analytica debacle. Its weak policy enforcement left the door open to exploitation of data users gave third-party apps, deepening the perception that Facebook doesn’t care about privacy.

Source: The real threat to Facebook is the Kool-Aid turning sour | TechCrunch

Mar 31, 2018 | algo, audio, networking, trends

A diagram included with an Amazon patent application showed how a phone call between friends could be used to identify their interests. Credit United States Patent and Trademark

Amazon and Google have filed patent applications, many still under consideration, that outline how digital assistants can monitor more of what users say and do.

Source: Hey, Alexa, What Can You Hear? And What Will You Do With It? – The New York Times

Mar 30, 2018 | mobile, networking, trends

How accurately can you be profiled online?

Source: How Cambridge Analytica’s Facebook targeting model worked — according to the person who built it – Salon.com

Mar 29, 2018 | games & graphics, networking, trends

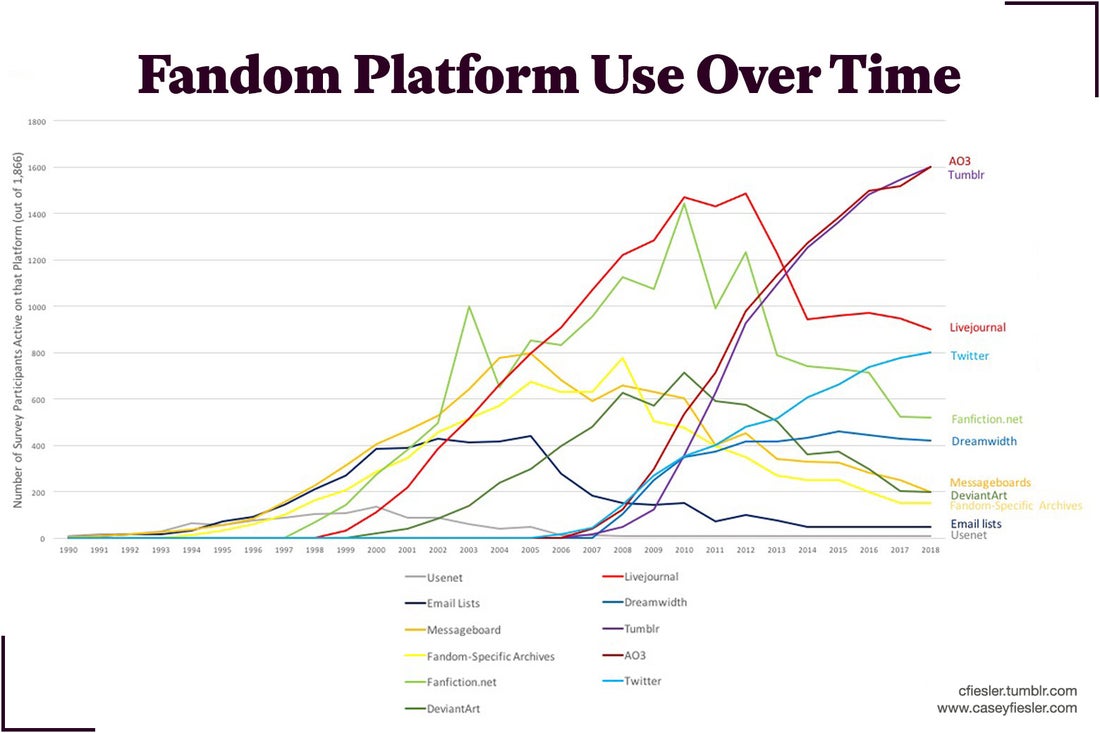

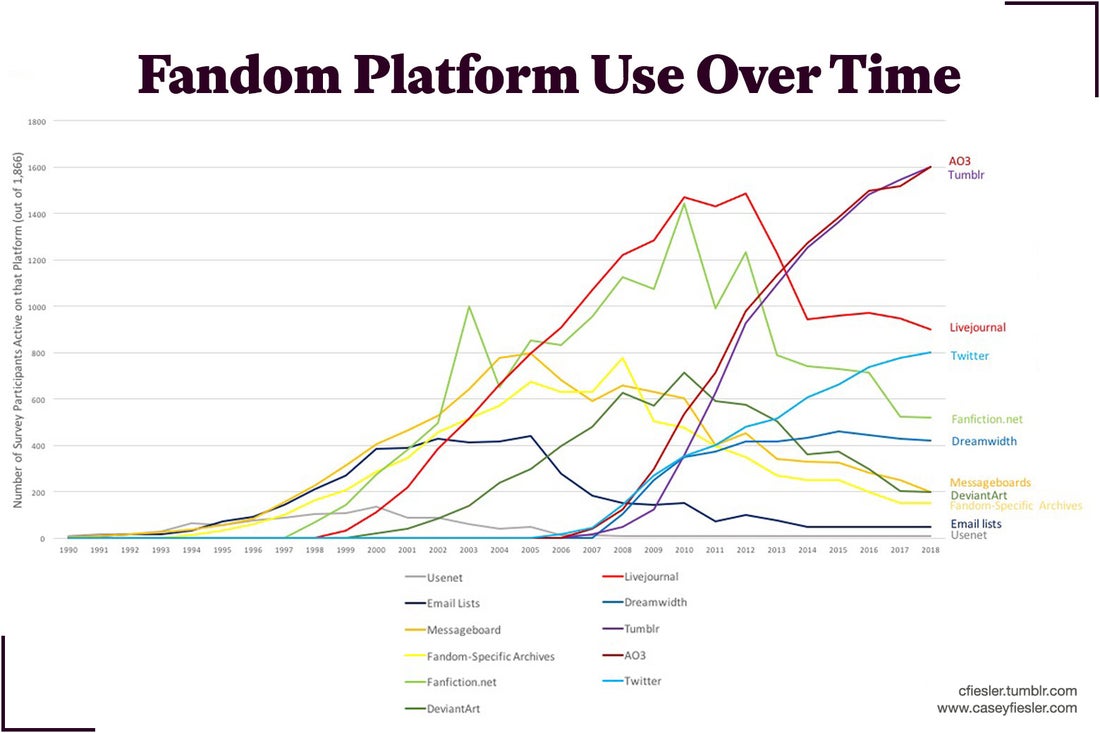

A fascinating survey details the migration patterns of pop-culture obsessives.

Source: Why did fans leave LiveJournal, and where will they go after Tumblr?

Mar 29, 2018 | networking, trends

They exploit our data and make us unhappy. They spread misinformation and undermine democracy. Is salvation possible for social networks?

Source: Can Social Media Be Saved? – The New York Times

Mar 22, 2018 | mobile, networking, trends

An “app,” in the eyes of your average consumer, is something you literally download onto your phone or computer. It’s a piece of software in your possession. Implied in this mental model is a sort of containment. An app is like a caged tarantula we can take out now and again. But when we put it away, it stays put away, because no one wants to wake up in the middle of the night with a giant arachnid on their face.

When Facebook began allowing apps to connect with its service to expand what users could do on the social network in 2007, this model was destroyed overnight. You were no longer downloading a piece of software that you somehow owned or that you somehow could unplug. You were connecting to a service that lived on servers, an omnipresent entity that was always there and always watching, even after you long stopped tending those Farmville crops or responding to those Words with Friends requests.

Source: Facebook Has An App Problem

Mar 21, 2018 | networking, trends

Things are getting worse for Facebook — WhatsApp co-founder Brian Acton jumped on the #DeleteFacebook bandwagon on Tuesday evening.

Source: #DeleteFacebook becomes a movement as former Facebook insiders turn on the company – Business Insider

Mar 14, 2018 | mobile, networking, trends

Automaker General Motors is said to be planning a new peer-to-peer car rental service, similar to existing offerings by Daimler-backed Turo and startup Getaround, to debut as early as this summer.

Source: GM said to pilot peer-to-peer car sharing through its Maven brand | TechCrunch

Mar 8, 2018 | networking, trends

For all categories of information — politics, entertainment, business and so on — we found that false stories spread significantly farther, faster and more broadly than did true ones. Falsehoods were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted, even when controlling for the age of the original tweeter’s account, its activity level, the number of its followers and followees, and whether Twitter had verified the account as genuine. These effects were more pronounced for false political stories than for any other type of false news.

Source: How Lies Spread Online – The New York Times

Mar 7, 2018 | networking, trends

Despite popular assumptions that young adults are social media-obsessed, new data suggests that many have considered a temporary—and even permanent—reprieve from their newsfeeds.

Source: Are Young Adults Growing Tired of Constant Social Connectivity? – eMarketer

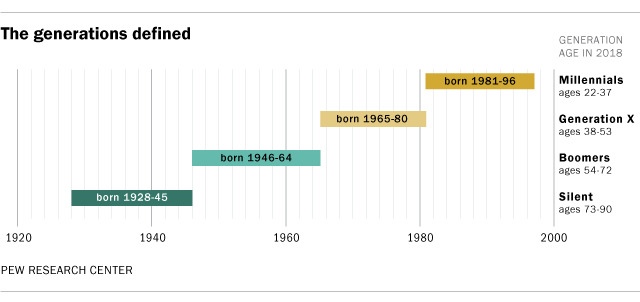

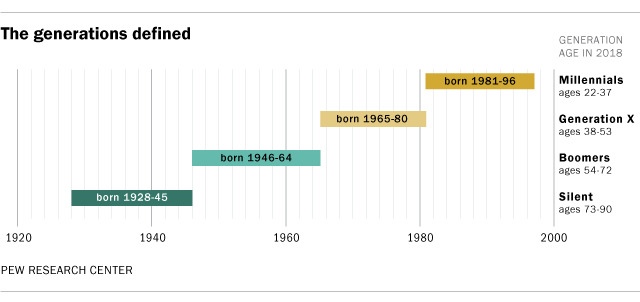

Mar 5, 2018 | trends

In order to keep the Millennial generation analytically meaningful, and to begin looking at what might be unique about the next cohort, Pew Research Center will use 1996 as the last birth year for Millennials for our future work. Anyone born between 1981 and 1996 (ages 22-37 in 2018) will be considered a Millennial, and anyone born from 1997 onward will be part of a new generation. Since the oldest among this rising generation are just turning 21 this year, and most are still in their teens, we think it’s too early to give them a name – though The New York Times asked readers to take a stab – and we look forward to watching as conversations among researchers, the media and the public help a name for this generation take shape. In the meantime, we will simply call them “post-Millennials” until a common nomenclature takes hold.

Source: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin | Pew Research Center

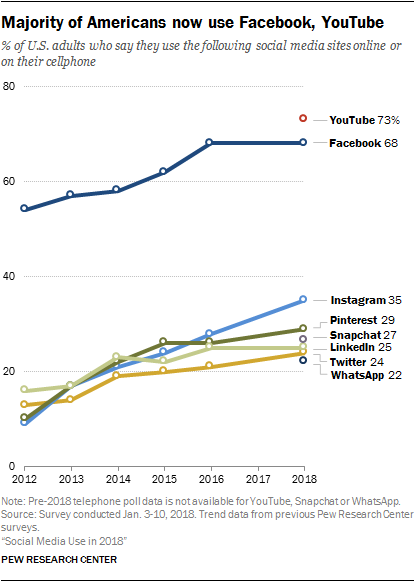

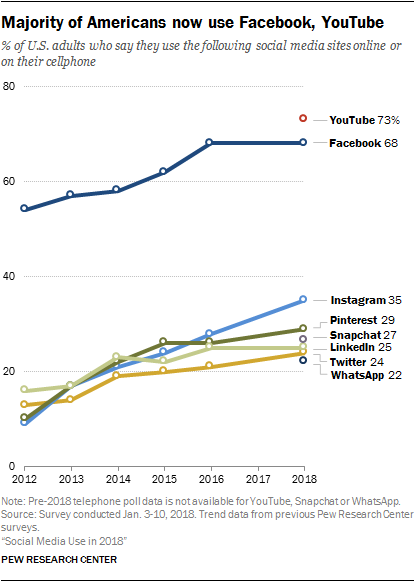

Mar 5, 2018 | mobile, networking, trends, video

A majority of Americans use Facebook and YouTube, but young adults are especially heavy users of Snapchat and Instagram

Source: Social Media Use 2018: Demographics and Statistics | Pew Research Center

Mar 1, 2018 | mobile, networking, trends, video

As automated advertising has matured, the structure of programmatic auctions has become more confusing. In 2018, marketers are looking to break through the clutter to understand what’s going on under the hood.

Source: Understanding Programmatic Auction Pricing Is a Major Priority for Marketers – eMarketer

Feb 28, 2018 | algo, trends

Google’s new Clips camera uses artificial intelligence to find cute moments with kids and pets. Is that helpful or terrifying?

Source: Google Clips camera review: The AI-powered camera takes photos and video for you. If you trust it. – The Washington Post

Feb 28, 2018 | networking, trends

E-commerce videos are a precision advertising tool which could put the nail in the coffin of traditional television adverts.

Source: How e-commerce video advertising will strike yet another blow to commercial TV