by Emily Cornett, Towson University

Healthy US civil-military relationships are vital to establishing clear strategic objectives. US involvement in the Vietnam War, and the war’s outcome, was the product of a dysfunctional relationship between the military and its civilian leadership that resulted in “unequal dialogue” and unclear political objectives. This relationship resulted in flawed strategy. The US policy of “limited war” produced an unintended gradual escalation of force resulting in the US failure to achieve its political objective to prevent the spread of communism.

US policy makers sought to prevent the spread of communism in Vietnam but were aware that a full-scale conventional war would be observed and interpreted by the Soviets and Chinese as an act of aggression against them. As Emile Simpson argues “members of the audience will have their own political interpretation of the event”, which is why policy makers pursued a limited gradual response.

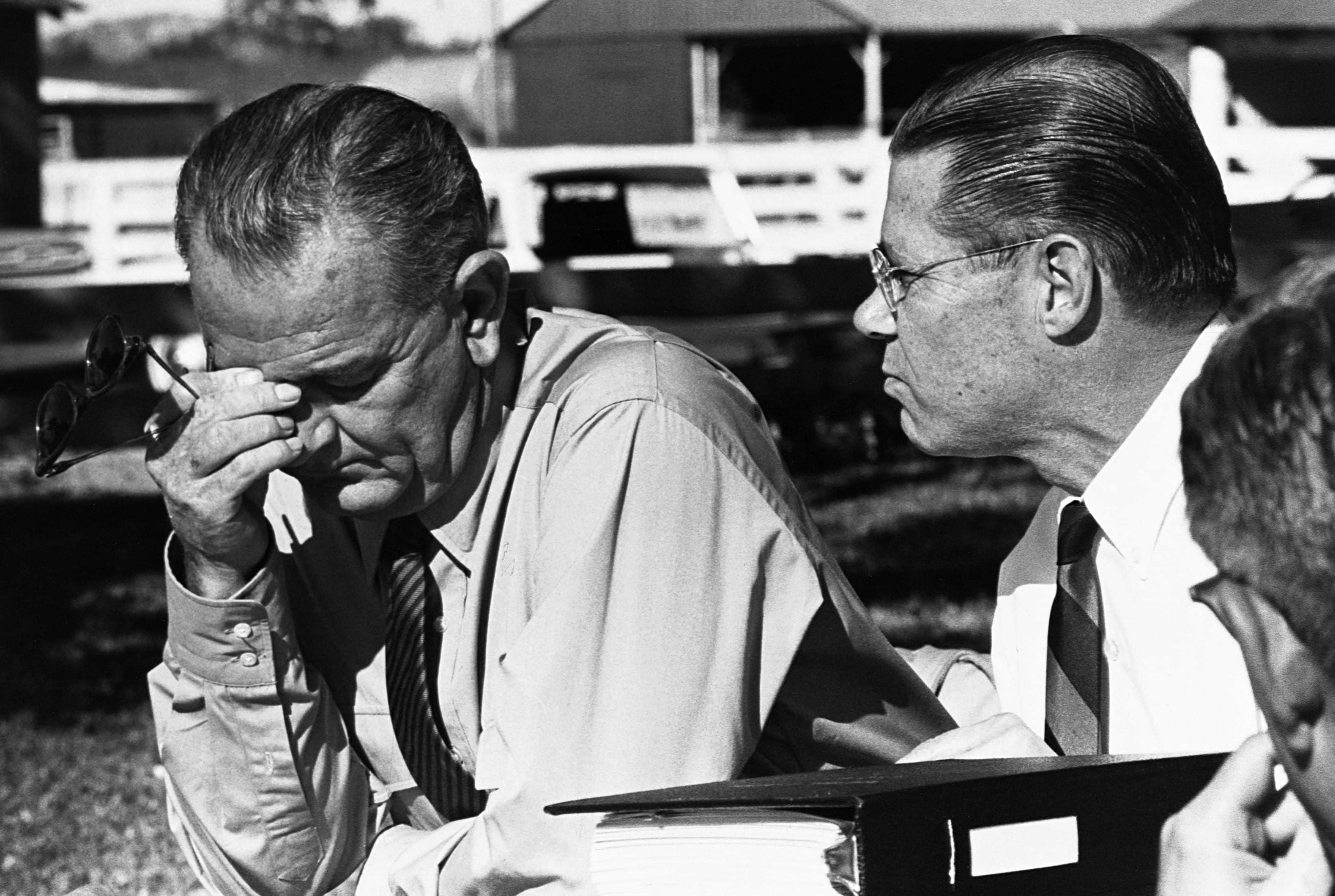

The Johnson Administrations approach in Vietnam, however, was forged with minimal involvement from the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). Andrew Bacevich states, civilians routinely disregarded professional military advice and allowed strategy to by dominated by civilian analysts. President Lyndon Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara “denounced an invasion in North Vietnam, placed whole targets off limits, mandated a foolish policy of gradual escalation, and signaled weakness through periodic bombing halts and peace initiatives.” This strategy was formed through consensus, dissenting opinions were suppressed, and senior military officers chose to “go along to get along”.

JCS chair General Maxwell Taylor sought to elevate himself in the political sphere, this fueled his relentless commitment to the administration’s strategy in Vietnam. General Nathan Twinning stated Taylor was largely responsible for the US involvement in Vietnam, “He was the only advocate of it, all the Navy and Marines and the rest of us were against it. He said we could fight a war, not a shooting war, but we would supply the equipment, the training, and the people to do the fighting for us.” US Army Chief Matthew Ridgeway had earlier warned, limited gradual involvement in Vietnam was dangerous and “would commit our armed forces in a non-decisive theater to attain non-decisive local objectives”. President Eisenhower stated in 1956, “we will not deploy our forces around the Soviet periphery in small wars.” Eisenhower was convinced that military victory in Vietnam was not possible. Despite fierce opposition, the US gradually began to deploy special forces to Vietnam as military advisors.

Without significant military consideration, the Johnson Administration believed strategic bombardment (Operation Rolling Thunder) and US training of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) would result in the surrender of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Yet, the US failed to understand its adversary and their capabilities, General Bruce Palmer states “we didn’t understand the Vietnamese or the situation or what kind of war it was. By the time we found out it was too late.” The US trained the ARVN to fight in a conventional war with the perception that the main threat to South Vietnam was not from within its borders but from the NVA. Emile Simpson states political space and interpretation must be controlled as there are external observers of conflict. Without control of wars’ interpretation, you will create new allies for your enemy. The Viet Cong (VC), an insurgency group within South Vietnam, did not accept US and South Vietnamese political objectives. The US and the South Vietnamese were unprepared to fight a counter-insurgency war and gradually the VC guerrilla units gained control in rural areas.

Strategic bombardment did not force the VC or NVA to surrender and the training of ARVN forces failed. For fear of wider geo-political implications, US Operation Rolling Thunder did not select bombing targets that would undermine NVA and VC capabilities. Bombing halts failed to disarm the enemy or render them powerless rather the NVA waited for conditions to improve because they were aware it was temporary. The NVA and VC rebuilt their strength and sought opportunities to catch the US and ARVN off guard in “hit and run operations” American advisors continued to denounce counterinsurgency operations because the military bureaucracy did not do what it was told to do, rather what it knew how to do.

Clausewitz argues that “war is an act of force and there is no logical limit to the application of that force, each side compels the other to follow suit, a reciprocal action is started which must lead, in theory, to extremes.” The US was forced to deviate from their strategy in order to match the use of force by NVA and VC opposition. The US increased the deployment of ground troops and resources, becoming directly involved in the Vietnam conflict. The Johnson administration refused to utilize military reservists leaving American forces undertrained and inexperienced, fighting an enemy it did not understand, with unclear and non-decisive objectives.

The US began to lose sight of who they were fighting and why, as friction on US troops increased, tactics, training, strategy, and morale began to breakdown. The US military continued to become weaker as the war in Vietnam lingered. For the North Vietnamese, the 1968 Tet Offensive was the culminating point of victory as US morale at home and abroad plummeted. The US public realized the Vietnam War was an unwinnable war. Democratic countries rely on public support to continue campaigns abroad, US perception had shifted, public support for the war and confidence in its military had diminished. One-year after the Tet Offensive, President Nixon announced the Vietnam War was ending. Because of the war’s flawed strategy, the US had exhausted resources and lost public support.

Civilian leadership had intruded where it did not belong believing the strategy of limited war would achieve their political outcome, halting the spread of communism. The US political objective in Vietnam failed due to the skewed perception of their adversary and a flawed civil-military relationship. The enemy always gets a vote, and the North Vietnamese had no intention of surrendering.