by Dagmawi Teferi, Towson University

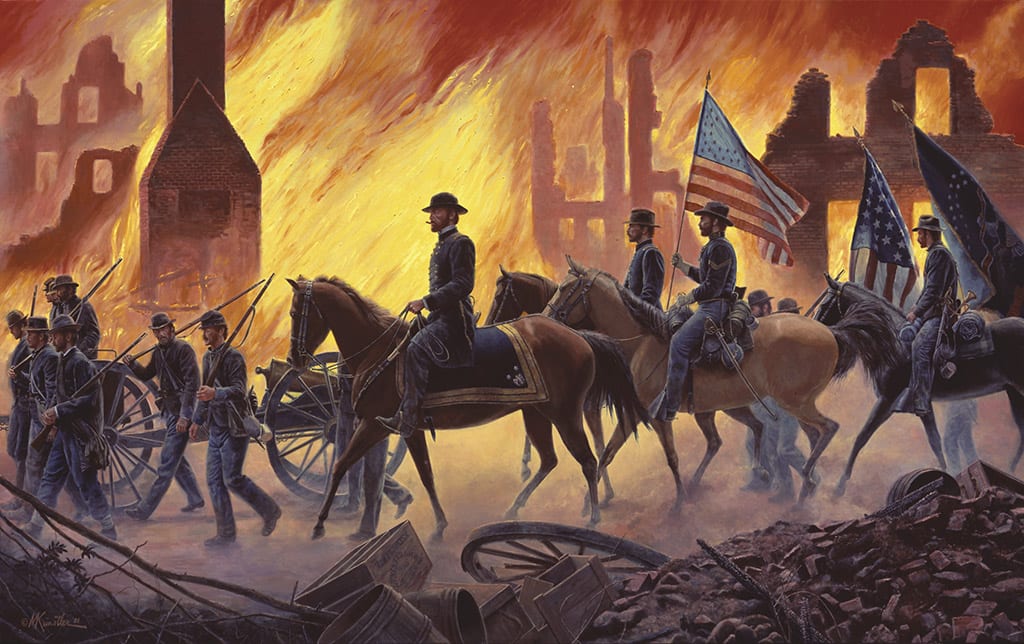

On November 15th, 1864 Union General William Tecumseh Sherman marched his army of 60,000 troops out of the burning city of Atlanta, Georgia to embark upon a military campaign that stretched 300 miles to Savannah, leaving utter destruction in their wake.[1]

The political objective of this campaign was to hasten the end of the Confederate insurrection. There were two strategic objectives for this campaign. The first was to cut off supply lines for the Confederate army battling the forces of Union General Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia. The second purpose was to inflict psychological damage on the civilian population of Georgia and break the will of the Confederacy. Through the employment of a scorched-earth policy, Sherman successfully disrupted the flow of supply of Confederate forces, broke the will of the civilian South to support the Confederate cause, and thus, hastened the end of the civil war.

Prior to his march to Savannah, Sherman successfully captured the city of Atlanta after a grueling months long campaign. Sherman sought the capture of Atlanta because it was the industrial hub of the Confederacy. Georgia was even called the “antebellum Empire State of the South.”[2] Its manufacturing capability and railroad system made it a vital asset to the Confederacy since much of the food, weapons, and ammunitions that supplied its armies came out of Atlanta.

By 1860, Georgia had 1,420 miles of rail tracks, second most in the South after Virginia.[3] The rise of railroads led to the rise of other industries like iron and other metals that were used for railroad construction. Georgia, Atlanta most of all, was connected to many other states in the Confederacy and kept supplies flowing throughout the South. This made it’s capture a top priority for Sherman.

However, capturing Atlanta alone would not be enough. The rest of Georgia still had the potential to keep the Confederacy supplied well enough to prolong the war. Thus, he devised his plan to march to the sea. After stripping Atlanta of its infrastructure and burning a significant portion of the city, Sherman’s army went on to do much of the same along the march to Savannah, believing that it would bring the war to a close much faster.

The Confederacy had sought to fight a war of attrition. Their objective was to defend their capital, Richmond, Virginia, by holding off the advance of General Grant’s forces long enough to wear down the North’s will to fight. They believed that they could win the war by simply not losing, similarly to how the American Revolutionaries won their independence from Great Britain. Sherman had the opposite in mind.

With the newly found will to win the war in the North following the capture of Atlanta and President Abraham Lincoln’s reelection in 1864, Sherman followed a “hard-war” policy. He believed that destroying Georgia’s capabilities to keep the Confederate forces supplied would be far more efficient for the Union than occupying it until the end of the war. In a letter to his friend General Grant, Sherman stated, “until we can repopulate Georgia it is useless to occupy it, but the utter destruction of its roads, houses, and people will cripple their military resources.”[4]

From a Clausewitzian perspective, by targeting the confederacy’s source of military supplies, Sherman was aiming to effectively disarm the enemy. Doing so would weaken the ability of General Robert E. Lee’s forces to fight at full strength in Virginia, allowing the Union army under Grant to be stronger at the right place and the right time.

Though he didn’t level another town like Atlanta, he allowed his troops to destroy property throughout the campaign, as long as it was in an area of continued resistance. They tore apart buildings, mills, factories, and houses then burned them when they were done. To destroy Georgia’s railroad system, his soldiers would tear out the tracks and melt them so they could be twisted into a loop that would go on to be called “Sherman’s neckties.” They also destroyed the stations and warehouses. By doing this, Sherman’s army cut off Georgia’s resources and supplies from the confederate forces fighting further North. This shortened the war as General Lee could not afford to maintain the fight against General Grant.

Yet, cutting off supply lines was only one part of Sherman’s motivation for this march. The other motivation relates to Clausewitz’s moral factors of will and hope.

Prior to his campaign, the civilian population of the Confederacy this far South had been virtually untouched by the war. They continued to be very supportive of the war and had hopes of victory. Through this march, Sherman wanted to show the people of the South that the Confederacy could not protect them from the Union. He thought that if he could inflict the psychological hardships of war on to the people of the South, he could break Southern morale and support for the war.

In the name of keeping his army fed, Sherman declared his troops would “live off the land.” Being cut-off from both communication and supplies from the North, Sherman’s forces had to forage for food as they marched towards the sea. Foraging parties were often miles ahead of the main force and could not be supervised, leading to looting and harm of civilians despite being against Sherman’s wishes. These foraging groups would burn everything they couldn’t carry, leaving the people they terrorized with nothing and further contributing to the demoralization of the South. Whether Sherman approved of their behavior or not, the result was the same. The South’s will to fight was fading.

With most able-bodied men off fighting against the Union, those who were left in Georgia were mainly women, children, and slaves. Spread of the news of Sherman’s destructive campaign and the hardships the women of the South faced eventually led to an increase in desertions of Lee’s army in Virginia,[5] further contributing to the hastened end of the war. Sherman’s strategy to “make Georgia howl” did exactly what it was intended to do.

By having his forces engage in what can be considered a total war against Georgia, engaging in the utter destruction of the land and the terrorizing of its people, Sherman successfully broke the South’s will to fight and the Confederacy’s ability to fight at full capacity. This allowed the Union be stronger at the right place and the right time in Virginia and bring the Civil War to an end. Though he cannot be given credit for creating the concept of total war, Sherman’s legendary campaign influenced how the U.S. would conduct warfare in the generations that followed.

[1] Anne J. Bailey. “Sherman’s March to the Sea.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 08 June 2017.

[2] Sean H. Vanatta, and Dan H. Du. “Civil War Industry and Manufacturing.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 06 June 2017.

[3] Ibid.

[4] William T. Sherman. “Letter to Ulysses S. Grant.” 09 October 1864.

[5] Bailey. “Sherman’s March to the Sea.” 2017.