By Jill Sullivan

Making a good first impression used to be as easy as a firm handshake and a clean resume. But companies are increasingly using digital personality tests to learn even more about the potential fit of candidates.

Personality tests predict traits like conscientiousness, extroversion, openness to new experience, agreeableness, and neuroticism (called the Big Five in psychology), among others. Knowing these traits can help a company improve retention rates and reduce absenteeism as well as predict potential employees’ productivity in the workplace and reduce theft.

“If you can fake on a personality test, what would prevent you from faking in other areas?”

But associate professor of management Nhung Hendy, Ph.D. says that even though personality testing continues to progress, the data supporting its validity lags far behind. Through her research, Hendy works to acknowledge and reduce bias in personality testing. She advocates for higher ethical standards in assessing personality and gaining personal data, especially as companies take personality assessment of candidates a step further.

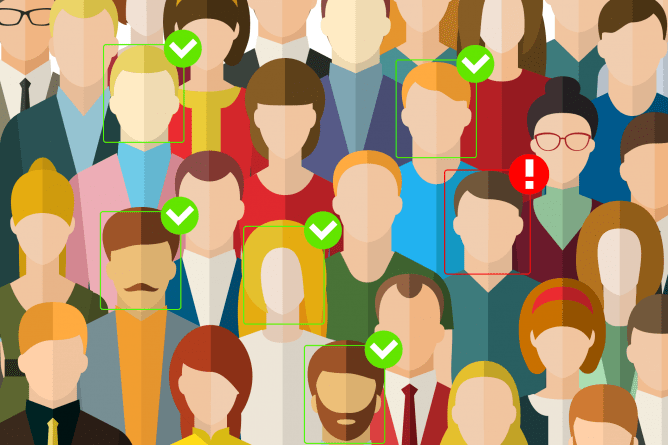

Some large companies, like Amazon and Google, are beginning to use personality assessment aided by machine learning and artificial intelligence to screen their job candidates—oftentimes, unbeknownst to the applicants.

“How many of us, including me, actually take the time to read through the small print of privacy agreements?” asks Hendy. “We give away a lot of our data every time we make a transaction on the internet. All that data can be crunched and analyzed to create a prototype of an employee, and they can use that to select people. There is potential for ethical abuse, but unless somebody complains about that practice, nobody will know.”

There’s also the potential for bias.

“How do you show that this recognition software has not produced adverse impact that significantly impacts minorities, more so than white males?” asks Hendy. “If the AI programmer has an unconscious bias, then the algorithm will be biased. Without proven validity there runs the risk of ethical and legal issues.”

Another ethical dilemma related to personality testing, says Hendy, is applicants giving false answers.

To better their chances of getting hired, candidates oftentimes fake their answers in personality assessments. And because personality testing allows companies to avoid the legal issues that can occur in other assessments, such as cognitive ability testing and work samples, which can lead to race and sex-based bias, some companies don’t care about candidates lying on these tests.

The problem with fake answers, says Hendy, is not only are the candidates misrepresenting their true selves but the company is losing its reliability to uphold other ethical standards.

“If you can fake on a personality test, what would prevent you from faking in other areas?” she noted.

Answers can also be unintentionally affected by emotion. If the candidate is happy, then they may indicate higher efficacy on test levels. But if the candidate is sad, then they may indicate lower levels of efficacy, also known as malingering.

Hendy says if candidates are able to notice their emotions at the time of the test and differentiate that between their general personalities, they will be able to answer the questions more honestly and therefore more ethically.

As for companies, they shouldn’t rely on personality testing alone. Although personality can predict performance, multi-measure tests hold a much stronger correlation than individual assessments.

“My recommendation to any organization who is thinking of using a personality test is always ask for evidence of validation, especially criterion and construct related validity, because content validity is not enough. It is subjective. If you are challenged in court, you won’t have a legal defense.”

Nhung Hendy, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the Department of Management. Her research interests include personality testing, talent management and business ethics.

Nhung Hendy, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the Department of Management. Her research interests include personality testing, talent management and business ethics.